Recent research reveals that 76 percent of LGBT people who have left the church are open to returning to their faith community.

According to statistics released by the Barna Group, only 9 percent of Americans are open to returning to faith and its practices after making a decision to leave their faith community. Yet recent findings from the Marin Foundation reveal that 76 percent of LGBT people are open to returning. This includes one-third of LGBT people raised in theologically conservative faith communities. Given the current state of the culture war, these two revelations are almost inconceivable.

This is not 76 percent of LGBT people maintaining a strong commitment to faith after leaving the faith community of their youth, or practicing a different faith, or joining a different faith tradition after leaving their original one.[i] It’s not a religious pilgrimage we’re talking about. This is a widespread desire for a religious homecoming.

What would make this homecoming a reality?

The latest estimate by Gallup reports that 3.8 percent of Americans identify as LGBT. If we estimate the U.S. general population at 320 million, then we are talking about millions of LGBT people, of whom

- 86 percent were raised in a faith community,

- 54 percent subsequently left;

- 36 percent are still practicing in the faith community they were raised in—a fact that we can celebrate as another hopeful reminder for a more constructive LGBT-religion conversation (see chapter four);[ii] and

- 76 percent of those who left are open to making a return!

This suggests that millions are ready for a new LGBT-religion conversation: not a culture war, but a mutually constructive dialogue!

Imagine if all those LGBT people who are open to making a return actually returned? And then over time, in partnership with their faith community, its leadership, and laypeople actively pursued a reconciled relationship. It would significantly alter the landscape of faith communities across the country—including those with conservative convictions on sexual ethics: Catholic churches, evangelical non-denominational churches, Assemblies of God, and the Southern Baptists, which, along with Judaism, make up half of the top ten most reported LGBT “raised in” religions and denominations.[iii] Not only so, imagine how this situation would significantly alter the landscape and worldview of the entire country? I can’t even begin to grasp the immense cultural ramifications. In one swoop this influx of LGBTs with a commitment to reconciliation would annihilate the whole social, political, and religious culture war system that has dominated American culture over the past generation.

The most pressing questions to be addressed are (1) What, if anything, would move millions of LGBT people from being open to returning to actually returning? and (2) What are the implications of such a homecoming for faith communities—especially those that are theologically conservative on gender and sexuality?

Of those religiously raised LGBT people who are open to make a return, 7 percent of them fall into the self-reported category of not knowing what would influence them to make a return. (They are, however, open to figuring it out.) The remaining 93 percent offered a range of possibilities. Given the three main reasons for leaving in the first place—negative personal experiences, theological differences, and institutional misgivings—what does the data show will actually bring LGBTs back to their religious community and its practices? When we asked LGBT people, “What would influence you to return to your faith community?” this is what they told us:

- Feeling Loved (12%)

- Given Time (9%)

- Faith Community’s Change in Theology (8%)

- No Attempts to Change Their Sexual Orientation (6%)

- Authenticity (5%)

- Support of Family and Friends (4%)

In comparison to the extreme cultural perception of what continues to keep the LGBT and faith communities apart, our findings are quite subtle. With the exception of the 8 percent of participants wanting to see a change in their faith community’s theology, most are not asking for dramatic ecclesial overhauls. Based on these responses, the LGBT community is asking that faith communities be what they say they are:

- loving (#1)

- patient (#2)

- realistic (#4)

- authentic (#5)

- supportive (#6)

The theology of sin, played up in the culture war as the defining characteristic of difference, again contributes very little within the overall participant dataset. Only 8 percent of participants would be interested in returning to their faith community dependent upon a change in theology; implicit in that statistic is that the other 92 percent would be open to return even without that faith community changing their theology.

Time

Let’s consider here the question of time, the second-most common response for what would cause LGBT people to return to their faith community (9 percent). We should start by understanding the beginning of the modern era of LGBT rights in the United States: the Stonewall Riots, a series of public demonstrations by the LGBT community in Greenwich Village, New York, in response to police raids on a gay bar. The Stonewall Riots eventually evolved into an organized movement for gay rights. That took place in 1969—within the lifetime of almost half of our study’s participants.

Sociologically speaking, we are just entering the second ever “out” generation of LGBT people.[iv] In less than 50 years the “gay community” moved from being an illegal underground smattering of individuals to an open, recognized, and active population seeking (and winning) legal rights and recognition throughout society. Additionally, the bulk of these cultural and political gains have come in the past decade. More has happened in a shorter timespan for the LGBT community than for African Americans, women, persons with disabilities, or any other minority population in American history.

Given this trajectory, time has two distinct cultural reverberations for the LGBT-religion conversation. First, the speed of such dramatic cultural, political, and religious change has raised the expectations for both communities. LGBT people and their advocates expect everything now. Meanwhile, people who identify as conservative (religiously or otherwise) are anxious to stop or slow what they perceive as a complete overhaul of society.

“I am who I am and believe what I believe today because of the best of what [my church] taught me.”

~Kevin, a 52-year-old gay man, raised in an evangelical church

Now is not inherently bad. An emphasis on now often helps keep people present in urgent matters. But now can become a problem. Both groups—those advocating change and those resisting it—focus on now to the point that they lose sight not only of each other, but also the social and political relations to each other. When we orient ourselves so tightly around upheaval and rapid change, we become reactive rather than constructive. Our public discourse, for example, quickly becomes heated and unstable. Turbulent times require intentionality, congruency, stability—values that require our commitment, values that become elusive when we focus exclusively on the now.

Change is inherently an unstable endeavor, and there are times and issues that call for urgent and radical overhaul—the contemporary LGBT-faith debate included. However, a culture outlives every change; thus, if there is not the time and space given to consider what will be needed then as opposed to now, the change that happens will never generationally persist.

There are ample historical examples to legitimize such a conclusion. In the wake of the Great Depression of the 1930s came the Great Migration by six million African Americans out of the American South and into the industrialized North. Cities like my own, Chicago, changed so rapidly that one of the most generationally damaging political decisions in American history was made: packing millions of the city’s new African American residents into crowded new housing projects on a small portion of Chicago’s South Side.[v] Today, 50 years later, Chicago’s South Side is the murder capital of the country, producing more homicides than that of U.S. troops in the Iraq-Afghanistan war in the same timeframe.[vi]

“I left the church because I couldn’t find one person who cared to listen to my story. I mean really listen.”

~Ben, a 29-year-old gay man

Also consider South Africa’s transition out of apartheid. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was lauded as a model of hope for all other countries recovering from similar ethnic oppression. Yet because of the forced, public political forgiveness implemented by the TRC, in exchange for absolution of crimes committed, less than a generation later intergroup violence remains a significant challenge.[vii] Quick changes in power structures and cultural normalcies need the utmost attention and care from all involved, otherwise all of the hard work and sacrifice made for the initial change is done in vain.

We have to believe that even in the quick changes occurring for the LGBT community, there’s still adequate time for the presenting issue, and assuredly there’s adequate time for the aftermath. As quickly as members of opposing communities want this mess to be solved and settled, there can be no substitute for the time needed for each side to take stock of their responsibility for the past, to assess what type of healing presently needs to take place, and to map out whatever future engagement will occur. The unfortunate reality is that in the case of the LGBT-religion culture war, both communities are trying to fight time by rushing a definitive conclusion that cannot be rushed. Regardless of the legal and cultural issues at play, each side has failed to prioritize relational stability for the future over political gain in the present.

Change is inevitable. That is a given. And it’s also a given that not all communities affected by change will think it agreeable. People of faith who resist legal same-sex marriage, open LGBT service in the military, employment protections, and general cultural acceptance, will continue to lose battles in the public sphere and continue to experience the uphill climb of the church’s perception problem detailed in Gabe Lyons and Dave Kinnaman’s now famous book unChristian. This doesn’t mean I want religious people to cower in a corner and refuse to stand up for what they believe. What I am asking is for people—especially Christians who are conservative on these moral and ethical debates—to live differently.

Jesus was revolutionary in both his message and his ability to build cultural capital within a society dominated by worldviews opposed to his. How Jesus lived his life and communicated his message did not weaken his conviction or dilute his impact. Engaging the culture prophetically from within earned him and his followers the respect and belief of many. He knew who he was talking to, where they were coming from, and he adapted his approach in ways that dignified their common context even in disagreement.

To Jesus, change was not dependent upon panic or upheaval. In fact, Jesus rebuked those around him when they started down that path (see Mark 14:44-50). Jesus and his followers instead lived change within the cultural and political and religious frameworks presented to them.[viii] They changed the world due to how they engaged, regardless of whom they engaged with.[ix]

“I would come back if I had the strength to do so.”

~Colleen, a 49-year-old lesbian

Relational healing between the LGBT community and the church cannot begin until reality is acknowledged and accepted. Reconciliation is a present task emerging from the memory of historical events. Culture is fluid; it looks different in different eras. What seemed beyond the pale in 1969 has become the new normal today, and what is generally acceptable in 2018 may be intolerable in 2049. We can’t predict future culture; we can only know ourselves, and conduct ourselves accordingly, in the present.

An implication of this is that we don’t have to agree with cultural norms to be faithfully present within our culture and influence its formation; we can do so through the practices of love, service, and submission to cultural authorities. Besides Paul and Peter’s repeated instructions how Christ-followers can add relational time by building credibility among those outside the faith,[x] Jesus’ responses to shrewdly asked closed-ended questions, attempting to pin him in one corner or the other, is a perfect model today for how we can engage time in the culture war. Instead of shutting down conversations with yes or no responses, we, like Jesus, have the opportunity to refuse to treat complex questions simplistically.

As recorded in the Gospels, Jesus was asked culturally and religiously divisive closed-ended questions 25 times by both his friends and enemies—eight times by the disciples, five by the Pharisees, four by the Chief Priests, four by Pilate and one time each by John the Baptist, the Jews, the Sadducees, and the woman at the well.[xi] Whether these questions were asked innocently or with malicious intent, he responded the same: elevating the question to a generalizable set of kingdom principles.[xii] Jesus’ social engagement gave the space needed to think, and ultimately to dialogue. Time must always be seen as an asset to the church, and anything that adds time to a relationship, to a constructive conversation, is worthwhile.

Time is so important because the cost of less time can be human life. I frequently get calls and messages from those whose LGBT loved ones took their life. It’s estimated that LGBT youth are four times more likely to commit suicide than other teenagers—and that number more than doubles when they feel rejected by their family.[xiii]

LGBT suicide is not just a problem for youth. In 2014 alone, three adult Christian LGBT friends of mine took their life because they felt they had run out of time with their faith. The struggle to live in the tension between sexuality and faith is only too real. It takes only a moment for a person, however well adjusted, to entertain a tragic thought.

I’m not saying that all, or even most, struggles with questions of faith and sexuality end in suicide. But time is irreplaceable and must be taken seriously. Life is not a debate to be won or lost. LGBT people are not talking points for an issue, politics, or theology. Each has a story, and they need time in conjunction with those who love them the most to sort through the grey areas of life.

Is the constant fighting and arguing simply a front to cover fear—fear that replacing conflict with dialogue will expose unaddressed vulnerabilities on either side?

The LGBT-religion culture war is, of course, not the only battle in the history of religion, nor is it the only battle in history whose opponents were so intimately connected. When asked about her country’s ongoing conflict between Catholics and Protestants, former Irish President Mary McAleese said that reconciliation would happen only when both communities found new concepts and definitions—a whole new language—to unshackle them from chains binding each side to their historic conflict. “Have we no confidence in the durability of the dogmas that we are protecting,” she writes, “that they cannot survive exposure to air? And if they cannot what does it say of their value in the first place?”[xiv] She rightly wonders if the constant fighting and arguing is simply a front to cover fear—fear that replacing conflict with dialogue will expose unaddressed vulnerabilities on either side.[xv]

A fear of vulnerability perpetuates conflict. Fighting, arguing, and even many attempts at persuasion wind up reinforcing relational walls, not breaking them down. Outright hate is sometimes the outcome. If we don’t give up the desire to be declared right, the fear that God has lost control, the luxury of hate, there is only one outcome: We lose time, and with it relational confidence and capital.

It can be different though. We can rebuild time. And we do so most efficiently by showing love (the #1 desire among LGBT respondents, at 12 percent) and demonstrating support (#6, at 4 percent) even when we don’t know what the future will hold.

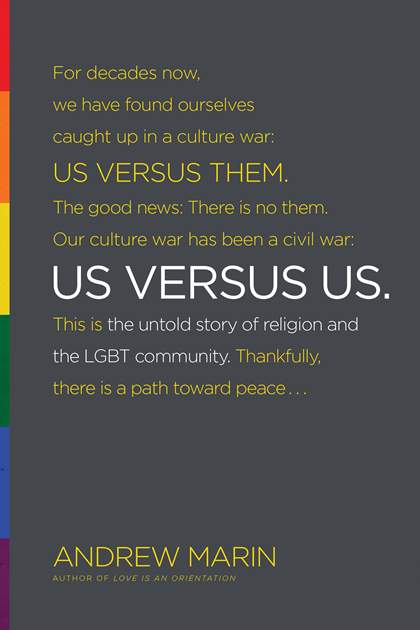

To read about the implications of the church showing love and support (and to learn what support actually means), please read the book from which this article was adapted: Us versus Us: The Untold Story of Religion and the LGBT Community by Andrew Marin. Copyright © 2016. Used by permission of NavPress. All rights reserved. Represented by Tyndale House Publishers, Inc.

To read about the implications of the church showing love and support (and to learn what support actually means), please read the book from which this article was adapted: Us versus Us: The Untold Story of Religion and the LGBT Community by Andrew Marin. Copyright © 2016. Used by permission of NavPress. All rights reserved. Represented by Tyndale House Publishers, Inc.

Did you miss our LIVE conversation with Alan Manning Chambers about LGBTQ inclusion? Catch the REPLAY here!"Once heralded as a hero in the Conservative Christian world as man who overcame his gay orientation, Charisma named Alan ‘One of the Top 30 Leaders Representing the Future of the American Church’ and World Magazine gave him their top honor, Daniel of the Year 2011, though both might now regret their choice because in June 2013 Alan shut down Exodus International and apologized for the harm he believes conservative Christianity has done to the LGBTQ+ community."

Posted by Christians for Social Action on Wednesday, April 3, 2019

Endnotes:

[i] Our data actually reports that 29 percent of LGBTs who leave their faith community join another. These results are from survey question #33a.

[ii] Chapter four will cover our findings on ongoing practice and, among other explorations, the reasons why LGBTs decided to continue practicing despite many real social, political, and theological differences.

[iii] For the full breakdown of all nine religions and their 57 denominations reported in the survey, see Appendix B.

[iv] For further information see Andrew Marin, Love Is an Orientation (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2009), 53-57.

[v] Nicholas Lemann, The Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and How It Changed America (New York: Vintage, 1992).

[vi] “Chicago Homicides Outnumber U.S. Troop Killings in Afghanistan,” June 16, 2012, accessed October 14, 2015.

[vii] Audrey R. Chapman, “Truth Commissions and Intergroup Forgiveness: The Case of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission,” Journal of Peace Psychology 13, no. 1 (2007): 56ff.

[viii] This concept of living change within existing systems is modeled by Jesus and explicitly taught by the apostles: See Romans 13:1-3; 2 Corinthians 1:5-11; 5:19; Galatians 5:13-15; 6:1-5; Ephesians 4:1-7, 12-13, 29-32; Philippians 2:3-4; Colossians 3:12-14; 4:1, 5; 1 Thessalonians 4:11-12; 1 Timothy 1:3-7; Titus 2:2, 8, 10; James 2:10, 18; 3:18; 4:11-17; 1 Peter 2:23; 3:8-12; 4:8-10; 1 John 2:9-11; 4:20-21.

[ix] Andrew Marin, “Would Jesus Fight a Legal Battle Against Same-Sex Marriage?” December 27, 2012, accessed October 8, 2015.

[x]See Romans 13:1-7; 2 Corinthians 2:5-11; Ephesians 5:21; 6:1; Colossians 3:18–4:1; 1 Timothy 2:1-2; 6:1-2; Titus 3:1-2; 1 Peter 2:13-17.

[xi] For a full breakdown of these questions and how Jesus followed the same pattern in each of his responses, see Marin, Love Is an Orientation, 178-82.

[xii] Marin, Love Is an Orientation, 178-82.

[xiii] “Facts About LGBTQ Youth Suicide.”

[xiv] Mary McAleese, Reconciled Being: Love in Chaos (Medio Media: London, 1997), 109.

[xv] McAleese, Reconciled Being, 109.