After listening to this episode of 20 Minute Takes, your ability to handle conflict, have difficult conversations, and engage in meaningful dialogue will level up; your friends and family will certainly thank you.

20 Minute Takes is a production of Christians for Social Action

Host: Nikki Toyama-Szeto

Edited & Produced by: David de Leon

Music: Andre Henry

Transcript

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (00:11):

Hello, this is Nikki Toyama-Szeto. I’m the Executive Director for Christians for Social Action and your host for 20 Minute Takes. This week we are welcoming Kristyn Komarnicki. She’s the Senior Director for Dialogue at Christians for Social Action and the Director of the program Oriented to Love. She helps us with some practical tips of what it means to transform conflict through curiosity and to navigate conflict with greater healing, compassion, and health. Kristyn, thank you so much for joining us on 20 Minute Takes.

Kristyn Komarnicki (00:50):

My pleasure

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (00:51):

Among your many talents, one of the things that I think you’ve become known for on our staff team and in this Christians for Social Action world, are these amazing candles that you sometimes make as gifts. Do you mind telling us about these candles that you create? They’re kind of inspired by the saints candles that the Catholic church uses.

Kristyn Komarnicki (01:14):

Yes, they are saint candles and I just love the idea. I feel like in Protestantism, at least the way that I was brought up, there’s a lack of symbols and rituals. And I’m very attracted to that and the beauty of the color and the light. I’m a big Frida Khalo fan – all the Mexican, beautiful Catholic symbols and colors have attracted me. I thought that I wanted to make these candles to honor people who might not be honored – social justice saints, people that were motivated by their faith to make a difference. If I know that somebody I care about is very fond of a particular person, I’ll make them a saint candle for that,

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (02:01):

I love that. You must have quite a paper collection because there are always these beautiful translucent things, almost like stained glass, but made out of paper.

Kristyn Komarnicki (02:12):

Yes I do. I never throw away a beautiful piece of paper.

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (02:16):

I could talk to you all day about the different creative endeavors that you have, but one of the things we are so interested in having you join us is that you

are the Senior Director of Dialogue for Christians for Social Action and the Director of the Oriented to Love program. One of the things that I’ve been so amazed with is the way that you approach difficult conversations and conflict. Can you tell us a little bit about what you see are the opportunities that exist in the midst of conflict?

Kristyn Komarnicki (02:53):

Sure. I think that conflict is something that everybody lives with. It is inevitable on any given day that we will have some kind of conflict, whether internal dissonance or external with our families or bigger as we engage with the news or current events. I am not a person who is wired to enjoy conflict. I’m not a conflict avoidant, but I do feel unsettled in the presence of conflict. And I really don’t like the way I feel within myself. I don’t like what it brings up – defensiveness, fear, anger, frustration. I don’t like those feelings. I have learned that when I lean into conflict, as opposed to avoiding it, I cannot only learn something, I find that it transforms or teaches me something more quickly than if I avoid it because avoiding it doesn’t make it go away.

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (04:04):

But doesn’t it make the pain go away if you can just avoid it?

Kristyn Komarnicki (04:07):

Maybe in the short term, but in the long term it usually just comes back with even more force because it festers. You gotta attack things, head on.

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (04:23):

If I were to do training on conflict it would be, see conflict and then 10 ways to avoid it! In society these days, especially when we’re talking about justice work or politics, it’s so divisive. You’re right that there’s not a way that we really can avoid conflict. So much of what we see modeled seems to make things worse. What advice do you have for folks as they’re trying to engage with people who have a truly different perspective or opinion and it’s a passionately held belief?

Kristyn Komarnicki (05:08):

When it comes to dialogue, I like to say that dialogue is not something that happens at the kitchen sink. It’s also not something you just walk up to somebody at the bus stop and say, let’s dialogue – right? Dialogue is an intentional activity that has to be agreed upon by both parties and for which you can and should prepare yourself. If you want to have real dialogue, as opposed to just two people waving their opinions at each other, if you want to lean into conflict and hope for a generative outcome, you need to get the agreement of the other person that we’re gonna have a conversation that’s going to be hopefully richer. And then prepare yourself for that.

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (06:00):

If you can unpack some of that preparation – what are some of the ways that you prepare yourself? What do we need to be aware of in the midst of conflic

t?

Kristyn Komarnicki (06:16):

When I see that there’s a conflict, for example, in my little circle of friends or my family, I try to start by some self examination. What is being triggered in me here? What are the emotions that I’m bringing to this situation? What am I carrying? And then I also try to see what I can affirm in the situation. Usually when we are in conflict situations we only see red, the danger, the scary parts. So I try to say, this person who I totally disagree with, who seems maybe a little unhinged, and their perspective of this particular thing -wow, they’re very passionate about it. Or “Wow, they really care about the people involved here.” Or “Wow, they’re really engaged and they’re really brave. They’re willing to bring their opinion to the surface and share it.”

I look for one or two things that I can affirm, which just puts me in a more positive mindset. Then the third thing I do is look for a question that is open ended and non-leading, that will help me get a little better understanding of where they are. So just to summarize, the first part is about self-regulation: who am I and what am I bringing to it? The second part is just setting out on a more positive step. And the third part is looking for a way that will invite a response from the person, a real compassionately curious approach. So for example, there’s a world of difference between me saying, “How could you possibly believe that?” Which has a question mark at the end of it, but there’s a hammer in my hand. I’m using that question to bludgeon my opponent and also to share that I totally disapprove of what they believe. So two things are happening the

re. I’m attacking and sharing my disapproval. There’s a world of difference between that and saying, “Please help me understand how you came to that conclusion. I really want to understand.” Now there’s no question mark there, It’s not technically a question and yet it’s 100% invitation, curiosity, compassion and respect. I’m assuming that they had a process by which they came to that conclusion. And I’m respectfully asking about that.

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (08:42):

So no matter how abhorrent the other person’s perspective or viewpoint might be, are you always able to find a point where you can be curious about?

Kristyn Komarnicki (08:54):

If I take the time! If I reflect. Now, my husband will tell you that I do a lot of heavy venting and this is behind the scenes. But when I actually go to approach that person, if I’m acting out of my best self (of course I fail many times) then I can make that happen. That’s part of that preparation. You can pray, you can ask for other people to pray for you, depending on how important the conversation or how risky it is. You can prepare.

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (09:25):

As you’re talking about that in this posture of curiosity, I can see how that really sort of shifts the energy of the interaction. You know people wanna feel heard, but you’re even taking it a step further. It’s not just listening to understand, but it’s actually like entering into that viewpoint and having a genuine curiosity, like in a sense honoring either the process or their story. Do you ever find yourself where that curiosity isn’t reciprocated? It seems like dialogue needs two people in two directions. It seem

s like that’s maybe a little bit of a dangerous point. What does dialogue look like when you’ve got one person who’s sort of self-regulating and trying to be curious, and another person who really wants to get their point across?

Kristyn Komarnicki (10:17):

Then it’s not a dialogue, and that’s fine. Like I said, you can’t make someone dialogue. It has to be an agreed activity. So what will usually happen in that case is that I will be quiet and maybe ask some more questions because either way I’m learning from this person and I’m getting an idea of why they’re situated the way they are. If they are not reciprocating with questions that are dialogue nurturing, then I can just continue to ask them questions. Honestly, people who aren’t interested in dialogue are usually interested in downloading their information onto you. I can absorb a certain amount of that, and then I sort of bring the conversation to an end. I can say, “Thank you so much for your time. I got a lot of insight out of this.” But if they’re not reciprocating with mutual curiosity, then it isn’t a conversation. So that’s okay.

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (11:10):

What you’re describing to me feels so much more positive and possibly helpful than a lot of the conflict that I see in my life and in my community. What are so

me of the common misunderstandings or myths that you think keep people from engaging with conflict in a healthy and curious way?

Kristyn Komarnicki (11:33):

We talked about the first one, “if I avoid it, it’ll go away.” I think that’s a fantasy. You know many marriages have dissolved because people just stop talking, right? Many relationships become estranged because people haven’t dared to sort of keep that going. Another misconception is that if I talk long enough, I will be understood. We shouldn’t necessarily go with that assumption that an understanding will be met. I always refer back to that prayer of St. Francis, “Lord help me want to understand more than be understood.” If I can come out of a place of fullness myself, where I feel centered and I’m in my belovedness, then I don’t need to demand or extract from anybody else being understood or getting what I’m getting. That can be a common misconception too – if I press into this long enough, I will be understood. I can’t control my conversation partner. I barely have control over myself most of the time.

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (12:46):

That’s true. And maybe related to that is this idea that if I say it more loudly you will understand it better.

Kristyn Komarnicki (12:55):

Absolutely.

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (12:56):

There’s something about conflict with people outside your family unit and then conflict with people with whom you have a lot of history or family members. Any advice for transforming conflict in those places where you have a lot of bad habits or it’s pretty easy to get hooked and derailed?

Kristyn Komarnicki (13:24):

I think just being really open about where you are in the process. One thing that I have found very helpful is to tell people I’m working on communicating better. “I know that in the past our interactions have gone this way and I really want something better for us. So I’m trying to do something different now, and this is what I’m trying to do. And if you see me doing that well please acknowledge it because I can use all the encouragement I can get. And if you see me acting in a way that’s not to that standard,

please call that out too.” You’re basically inviting someone else into your process and you’re taking responsibility. We make so many mistakes along the way anytime we’re trying to learn a new skill or develop an especially challenging skill, which I think dialogue is especially challenging.

I’ve learned to just stop mid statement and say, “Oh, you know what? I just asked you a closed ended or very leading question. I’d like a redo.” I have asked for hundreds of redos over the last few years and I have never once been refused. I think people are so intrigued and sort of caught off guard. And then they can actually hear your thought process because they see you transforming a poor question into a rich invitational question. Then it’s instructional for everybody.

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (14:46):

Kristen, next time I’m having a fight within my family I’m going to invite you and your calm, demeanor to help guide us through. Particularly when it comes to really divisive issues with people we care about a lot, it seems like it’s really hard to ask “Why are they thinking what they’re thinking?” It’s hard to have genuine curiosity about people you’ve got a lot of history with.

Kristyn Komarnicki (15:29):

Yes, because we project the past onto them and we are not expecting them to do things differently. And your idea of calling me in there – I know you’re kidding, but how I found that to be super helpful is we have a family therapist. This outsider who is neutral can listen for those patterns that are mutually destructive and can call us to new ways of thinking and seeing. That has played a huge role in my life in terms of improving my communication.

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (15:58):

Do you think that dialogue in a Christian setting, the church or with Christian activists have their own particularities that we should be aware of? When it comes to things related to God or justice issues there is the presumption that something is more theological or more right. Like the dialogue or the conflict is winnable. Have yo

u noticed any ways Christians fall into something that actually makes it hard to be curious when you’ve got things like fundamental beliefs about God on the line or the pursuit of serious justice issues?

Kristyn Komarnicki (16:47):

Because we’re so emotionally, spiritually, mentally tied to our faiths, our faith is rooted in something deeper than just our minds.

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (17:05):

Yeah. It matters so much.

Kristyn Komarnicki (17:06):

Yeah, and our childhood, our emotional experiences, and what it means to be part of this community, our identity as Christians. On the one hand,

it can be a good thing. We all believe in Jesus, right? Let’s just stick to the top level. Like we all believe that Jesus was God and man, so that can help provide a foundation, but it can also feel very threatening when somebody else’s view contrasts with yours. In the Protestant tradition I grew up in there was very much this idea of this is right. This is the right way to look at something. And that is the wrong way. So it can threaten our whole sense of identity if we give somebody else the benefit of the doubt or we say, “Wow, you see things very, very different from me, but I still see the hand of God in you. I still see the holy spirit at work in your life.”

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (17:59):

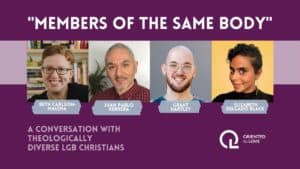

One of the things that you do a lot of work with is a program called Oriented to Love and part of that are Oriented to Love dialogues. Can you describe those, and is there anything that’s happened in the context of these dialogues that’s really informed how you engage with conflict or holding spaces where people have really different perspectives?

Kristyn Komarnicki (18:25):

These dialogues have taught me so much. So just to explain briefly, an Oriented to Love dialogue is a group of 12 people, six people who identify as s

traight or cisgender and six people who identify along the continuum somewhere, LGBTQ plus, et cetera. All of them are Jesus followers. All of them say that Christ is central to their faith walk. And they agree to come together in the posture of a learner in mutual vulnerability and they agree to be brave with each other. There’s an eight week preparation process where they start practicing vulnerability by introducing themselves, sharing some of their baseline beliefs, and sharing their hopes and fears about the dialogue itself. They come together and most of them are meeting for the very first time. It’s a completely confidential experience, but we spend a weekend together asking each other hard questions across deep differences and listening to each other in love. So that’s a very, very quick description of what happens. And the second part of your question was what have I learned?

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (19:37):

Yeah. From watching from leading these for so many years, how has that influenced how you view conflict or your approach to conflict?

Kristyn Komarnicki (19:48):

Oh, in so many ways. At one level, just watching people walk bravely towards a weekend of discomfort has given me a sense of the courage that it tak

es to lean into hard conversations and to know that your assumptions and beliefs will be challenged. I am not engaged in the conversation. I am holding the conversation. In some ways it’s much more relaxing for me to sort of be on the outside, holding people than to be in the midst of it. I see their courage and I see the beautiful gifts of relationships across deep differences. One of the things I personally learned is I used to think that when people were mad at me or disagreed with me, that just used to take me out- I would just be done for a couple of days. I would just be so distraught and now I see there’s some real riches in here. If we dare to lean into it. For one thing, I’m going to learn something I didn’t know before. I’m going to be challenged to articulate my beliefs. It’s so easy to be lazy with what we believe. I believe this because my mom told me. I believe this because I read it somewhere. But when someone’s asking real compassionately curious questions that I’m forced to articulate, “I was really influenced by this certain thing, but I have never actually experienced that myself. So I don’t really know why I believe that.” Iron sharpens iron, right?

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (21:23):

Do you have a story that illustrates what it is that you hope for when you see somebody leaning into conflict?

Kristyn Komarnicki (21:30):

The first one that comes to my mind is the one I’ll share. There have been so many. One really beautiful moment happened when – for lack of better terms I’ll just use the “conservative” label – a conservative pastor, straight was in a group and there was also a progressive pastor who was gay. This progressive man kep

t using scripture, kept quoting scripture and telling the stories of Jesus in really beautiful ways. I could see that this conservative pastor was intrigued by the progressive man using this, all just sort of marinating in scripture. He said, “Wow, you are talking more about scripture than anybody else in this dialogue. And when I came into this I assumed that anyone like you, a gay man living in a partnership with the same sex partner, didn’t respect or didn’t have a high view of scripture, or didn’t love the scripture, so didn’t understand the scriptures like I do. And yet I see that you have a very vibrant relationship with the scriptures.” So that was a beautiful moment. And those are the moments that, of course, I look for when people can recognize the Imago Dei in someone they thought couldn’t possibly have what they think they have.

Nikki Toyama-Szeto (22:55):

I appreciate the vulnerability of that pastor saying, this is actually what I came in with and then this is what I noticed that sort of changed that mind. Kristyn Komarnicki, Senior Director of Dialogue with Christians for Social Action, thank you so much for joining us. The work that you do and helping to make soft places for really difficult conversations is such a great ministry. We’re so grateful for the work that you do.