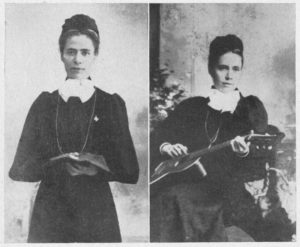

(1828-1906)

(1828-1906)

Described by contemporaries as “touched with genius” and “the most distinguished woman of the 19th century,” Josephine Butler launched the first international anti-trafficking movement on behalf of prostituted women.

Born into the prominent family of John Grey, a slavery abolitionist and cousin to a prime minister, Josephine was raised in a household that was politically influential, deeply religious, and characterized by a sense of social responsibility and “fiery hatred of injustice.” In 1852 she married George Butler, a respected scholar and cleric. The death of their only daughter, Eva, in 1863, led Butler to seek solace by ministering to people with pain greater than her own.

Against the advice of family and friends, Butler began by visiting Liverpool’s Brownlow Hill workhouse. There she encountered destitute, desperate, and “criminal” women, including unwed mothers and prostitutes—those whom society viewed as beyond hope of restoration.

Undaunted by cultural norms, Butler visited these women, built friendships with them, and ultimately began offering former prostitutes refuge in her own home. While also campaigning for women’s suffrage and higher education, in 1867 she founded the House of Rest, a home to rescue those in danger of falling into prostitution.

But the great crusade of Butler’s life was her fight against the 1864 Contagious Diseases Acts (CDA), the first of a series of acts that legalized prostitution in several of England’s towns where military troops were garrisoned. Butler rightly viewed this as government-sanctioned enslavement of women and argued that the CDA rendered them “no longer women, but only bits of numbered, inspected, and ticketed human flesh, flung by Government into the public market.”

In 1869, she helped found the Ladies’ National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts (LNA). Under her direction, the LNA relentlessly led petition drives and processions, published pamphlets and monthly newsletters, sponsored political candidates, and garnered the support of such well-known figures as Florence Nightingale and Victor Hugo. Eventually, Butler’s campaign for abolition spread to the European continent and led to the formation of the International Abolitionist Federation, which she helped establish.

Butler was unique in her day. Instead of pouring out moral outrage on those who were caught up in prostitution by force, fraud, or economic necessity, she reserved her wrath for those who tolerated prostitution and engineered its expansion. She understood that lack of education and work opportunities drove more women into prostitution “than any amount of actual profligacy.”

Instead of pouring out moral outrage on those who were caught up in prostitution by force, fraud, or economic necessity, she reserved her wrath for those who tolerated prostitution and engineered its expansion.

She insisted on the humanity of those caught up in the sex trade: “When you say that fallen women in the mass are irreclaimable, have lost all truthfulness, all nobleness, all delicacy of feeling, all clearness of intellect, and all tenderness of heart because they are unchaste, you are guilty of a blasphemy against human nature and against God.”

Moreover, she rocked the social norms of her time, not only because she spoke about the shameful subject of prostitution, but because she dared to address audiences of men at a time when women were expected to be silent regarding public affairs.

Butler saw her campaign as analogous to that of abolitionists like William Wilberforce and her father, who a generation before had fought against the African slave trade in the British Empire. She cleverly criticized the CDA’s existence with this question: “Shall the same country which paid its millions for the abolition of negro slavery now pay its millions for the establishment of white slavery [the Victorian-era euphemism for sex trafficking] within its own bosom?”

The CDA were not repealed until 1886, but by then Butler had already succeeded in revolutionizing the role of women in politics and elevating countless women, viewed by most as “the sewers of society,” to places of safety and positions of dignity and respect.

Political, cultural, and media elites are increasingly raising alarm over what has become one of the world’s largest illegal commercial sectors—the trade in human beings. The US Government estimates that 600,000 to 800,000 men, women, and children are trafficked across international borders each year. Of these, approximately 80 percent are women and girls, and the majority of victims are trafficked for purposes of commercial sex. The Trafficking Victims Protection Act exists to improve upon and expand existing anti-trafficking laws.

Today’s movement for the abolition of sex trafficking is a rekindling of Josephine Butler’s earlier crusade. Butler’s model of courage and selflessness is not to be forgotten as we use every available weapon to fight the modern slave trade.

Lisa Thompson is director of anti-trafficking at World Hope International. This essay was adapted from a longer article published in the Spring 2006 issue of Christian History & Biography magazine and is reproduced here by kind permission of the editors.