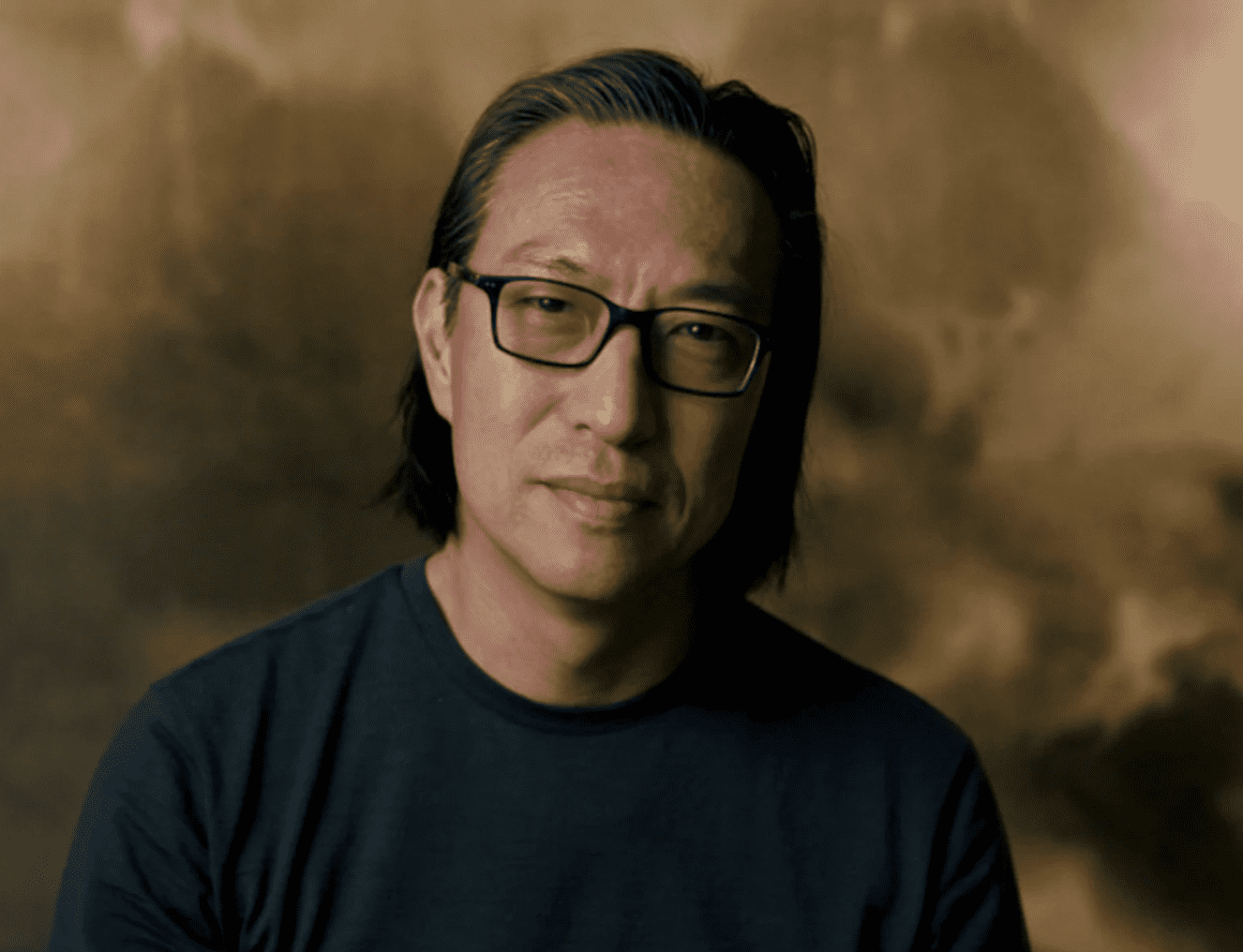

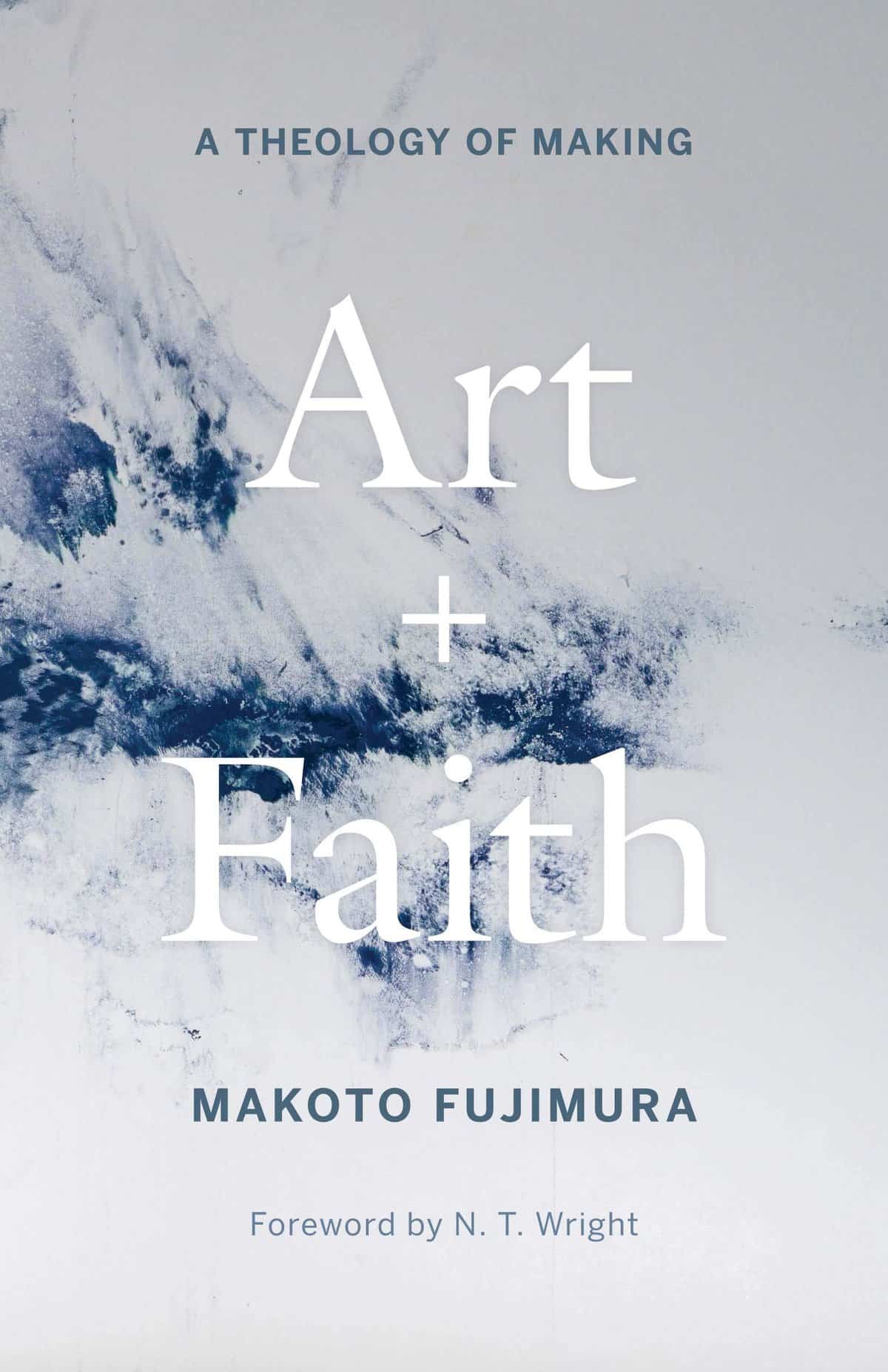

Earlier this year, artist Makoto Fujimura wrote Art + Faith: A Theology of Making. The concept was turned into a series of videos by Windrider. Below we talk with Fujimura about his art, the Japanese tradition of kintsugi, and the intersection of beauty and justice.

You have been called “an accidental theologian.” Sometimes God speaks to us in ways and degrees that we maybe weren’t anticipating—in your case, through art and the creative process. How can God surprising and teaching us in different ways invigorate our faith?

If God is indeed the Maker, then it makes sense that we are created to be creative. I actually believe that it is in our making that we discover the Spirit’s call for us and the church. What seems to us as marginal, surprising, or gratuitous may be at the heart of God’s redemption and God’s New Creation.

In the Japanese tradition of kintsugi, you remake something broken and fashion it into something new that doesn’t hide its brokenness. Why are we so fearful of being broken and wounded, and how can we begin to change our thinking concerning pain and woundedness?

Western ideas of “perfection” as an industrial and consumer endpoint—and the incessant drive to market such inhuman ideals (to create a desire in us for things that we know are impossible to attain)—have resulted in our avoidance of pain and suffering, brokenness and imperfection. The Japanese honor the imperfect, resulting in the beholding of worn objects (wabi) and rusted surfaces (sabi), at least traditionally. Kintsugi also reflects the post-resurrection appearances of Jesus as he is risen as a wounded human being glorified, and it is “by His wounds that we are healed” (Isa. 53:5-6).

Our world has big issues of injustice and brokenness. What can a theology of making teach us about where we go from here in tackling important justice issues today?

Justice is not true justice until the oppressed find themselves beautiful. Conversely, beauty calls us to true justice. The kintsugi process points to both simultaneously. We need to begin by beholding the brokenness, and see the fractures as the entry point into the New. Theology of Making begins with mending the fractures to make New.

We live in a utilitarian society, where we think everything, including ourselves, must be doing something and have use. What happens when we deny this belief system and begin to run towards a theology that we were created to have value outside of what we do?

What I have called Utilitarian Pragmatism is pervasive in cultures that assume that the Darwinian survival is the only way. Jesus’ message and his life offer a path to see abundance in the midst of scarcity, to love our enemies despite the cost. The way of mercy and beauty seems so counter to what is deemed useful for survival, but in fact is an antidote exactly because it opposes our base instincts. The gospel is good news to the marginalized because it is upside down, and those on the margins are welcomed into the Feast.

What I have called Utilitarian Pragmatism is pervasive in cultures that assume that the Darwinian survival is the only way. Jesus’ message and his life offer a path to see abundance in the midst of scarcity, to love our enemies despite the cost. The way of mercy and beauty seems so counter to what is deemed useful for survival, but in fact is an antidote exactly because it opposes our base instincts. The gospel is good news to the marginalized because it is upside down, and those on the margins are welcomed into the Feast.

As you look back on your artistic career, have there been a couple pieces that you’ve done that have been especially meaningful to you?

It is impossible to pick two. The Four Holy Gospels commission was certainly one of the most significant, and the Silence and Beauty series, Ki-seki, Walking on Water, Golden Sea, Water Flames, Columbines, as well as the most recent Rhapsody, stand out.

What advice would you give to the person who wants to pursue either a vocation or a hobby in the arts and who has been told that that is not a worthwhile venture?

We are all artists of the Kingdom already. To deny that impulse in any way is to deny the gospel. On the other hand, on this side of eternity, if you need someone else’s validation to pursue being an artist, then I advise that person to not be a full-time artist, but to apply their creativity through other worthwhile venues. It’s simply too hard of a path unless you feel it’s the only way you have to “Glorify God and Enjoy Him forever.”

Learn more about Makoto Fujimura’s art and writing.