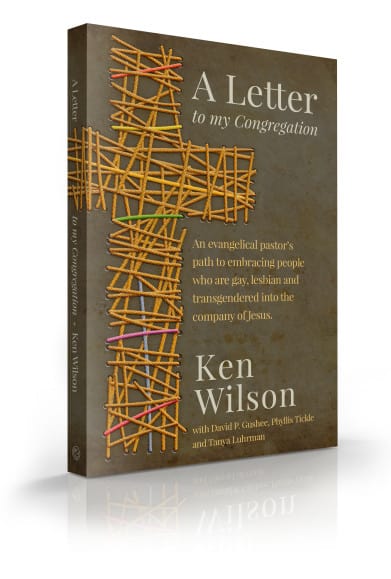

I just counted the books on my selves about faith and homosexuality: I have 51. I also just finished reading Ken Wilson’s A Letter to My Congregation: An Evangelical Pastor’s Path to Embracing People Who Are Gay, Lesbian, and Transgender into the Company of Jesus (David Crumm Media, 2014). It is the best of the lot, largely because Wilson proves that the inclusive side can “take Scripture seriously.”

One way he does this is by retracing his own journey. Like so many evangelical pastors, Wilson instinctively held the traditional view. Then he encountered a person, born with female genitalia, who had undergone gender-reassignment surgery in order to bring his body into alignment with his male gender identity. The transgendered person’s home church insisted that he reverse the surgery and revert to his birth gender. As an evangelical pastor, Wilson turned to the Bible for guidance and noticed a trajectory concerning the Scriptures’ closest equivalent—eunuchs. Although eunuchs are excluded from temple worship in Deuteronomy 23:1, Isaiah 56:4 anticipates their inclusion, and New Testament passages (such as Matthew 19:12 and Acts 8:27-39) confirm their acceptance. If this is the case for eunuchs, might something similar apply to gays and lesbians?

As Wilson recounts with profound honesty and vulnerability his struggle to understand, we sense his deep commitment to Scripture and are ushered into the heart of a pastor. Called to be a shepherd, Wilson keeps finding wounded sheep—LGBT people who have been hurt by the church. How is he to relate to these people and their pain? Should he exclude these injured sheep from the flock to fend for themselves? The resulting tension causes him to study the Scriptures as someone preparing to jump out of a plane might read parachute instructions. In her introduction to the book, Phyllis Tickle describes this beautifully as she imagines the task of a clergy person like Wilson as that of spending “agonizing hours and days and weeks pouring studiously over sacred texts in relentless, ongoing attempts to penetrate the mysteries contained there, to discover their wisdom, their instruction, their relevance, and to consider the means and repercussions of their implementation within our here and now.”

As a result of his study, Wilson contends that the Bible shouldn’t be used, as it often is, to wound LGBT sheep but instead we must understand the context in which the original words concerning same-sex relations were used. If, for instance, someone had used the phrase “Don’t be gay” 50 years ago, most North Americans would have understood it to mean “Don’t be lighthearted.” The meaning of the phrase has changed immensely. Similarly, in order to understand the biblical words used, we’ve got to understand what they meant in their context.

Ancients had no equivalent for the modern word “homosexual.” Romans 1 uses the phrase “men committed shameless acts with men,” and two words with ambiguous meanings are used in other New Testament passages, arsenokoitai (1 Corinthians 6:9, 1 Timothy 1:10) and malakoi (1 Corinthians 6:9). Wilson synthesizes the substantial research done on the first-century context to show that same-sex relations took place primarily in the context of temple prostitution, pederasty, and sex with slaves. These verses are important as we think about modern prison rape or male prostitution. But first-century people reading such verses would not have thought of them as prohibiting a faithful, egalitarian, commitment between two people of the same sex.

The most important contribution Wilson makes is that he convincingly draws a corollary between the modern debate over same-sex marriage and the debate over food narrated in Romans 14 and 15.

The most important contribution Wilson makes—one that may be original to him—is that he convincingly draws a corollary between the modern debate over same-sex marriage and the debate over food narrated in Romans 14 and 15. We look back on the food controversy and think, “Ah, it is something like the squabble between meat-eaters and vegetarians.” But Wilson reminds us that for early Christians, questions about food sacrificed to idols would have seemed vitally important, just as the same-sex marriage debate is important to us today.

The apostle Paul characterizes the issues involved as “disputable matters” (Romans 14:1). Paul’s concern is that the early Christians, even in important theological matters related to the law and idolatry, “Accept one another then, just as Christ has accepted you, in order to bring praise to God” (15:7). Again and again the readers of Romans are encouraged to refrain from judging each another, for each of us is responsible for our own conscience before God. Through his study of Romans 14 and 15, Wilson shows how allowing convinced Christians to advocate for full inclusion of LGBT people in the church (as a way of respecting their conscience before God) can be a legitimate way of taking the Scriptures seriously.

Written as a letter to his congregation, Wilson’s book will, I predict, act as a modern-day epistle. In the context of his own denomination, the Vineyard, which asserts that marriage is “a covenantal union between a man and a woman,” the book is an act of loyal opposition. Wilson appeals to the deepest wisdom of the Vineyard movement—that Scripture is not self-interpreting but rather interpreted rightly only through wrestling with the Spirit. I suspect that, like Jacob, Wilson will emerge from this wrestling match wounded (from the opposition he faces) but also endowed with the blessing of his healing work—a blessing that will inspire us all to delve more deeply into the Scriptures—with the Spirit’s help.

Tim Otto’s book Oriented to Faith: Transforming the Conflict over Gay Relationships was recently released by Wipf & Stock. He can be followed on Facebook.