Originally posted April 21, 2022

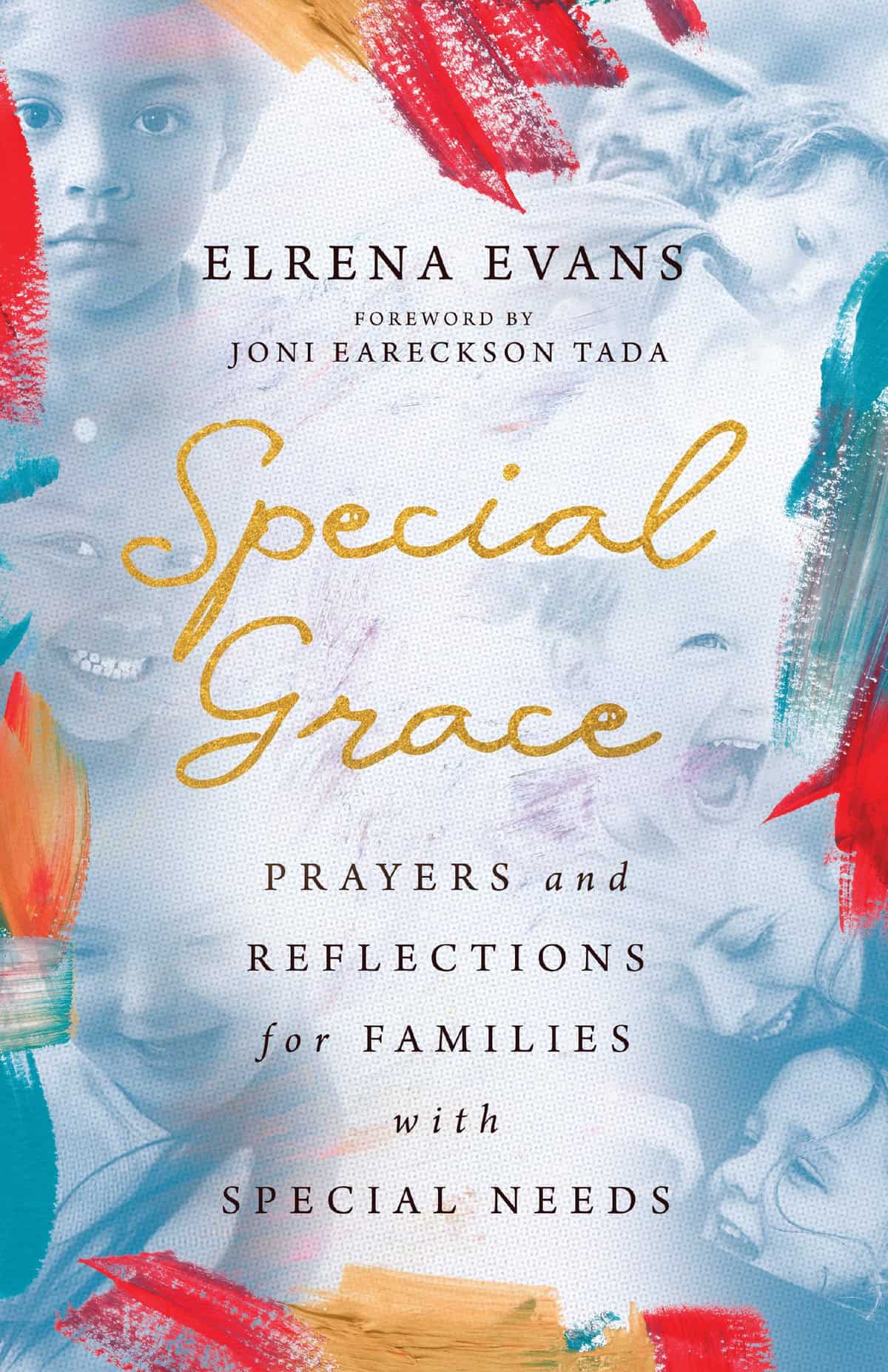

We spoke with Elrena Evans about her new book, Special Grace: Prayers and Reflections for Families with Special Needs from InterVarsity Press. Below you’ll find our conversation, as well as an excerpt from Evans’ beautiful book.

What do you do when you’re just not able to pray?

What do you do when you’re just not able to pray?

I love this question, because despite being a writer, my prayers don’t always initially form as words. I’ve danced my entire life, and my prayers often form as movement. In the moments when my heart just does not have words, I dance. And I trust that is a prayer that God understands.

Friends have told me that when they cannot find or form the words to pray, they cook, hike, garden. Even sleep. I believe that all of these things are prayers—that the God who formed us isn’t limited by human speech, but is present and hearing the unspoken words of our hearts in our movements, in our cooking, even when we sleep.

My hope for Special Grace is that the written prayers will encourage readers to find or create prayers of their own, whether those also form as words or whether they form as a deep sigh, a walk in the woods, or a newly-planted flower.

Why do you think “typical” Christians are generally so uncomfortable with and/or insensitive (clueless…) about special needs and differences?

I think people in general can be uncomfortable with difference. And I think sometimes when this discomfort manifests in churches, it’s because we have confused order with piety or devotion. Sometimes I wonder if, in our attempts to communicate with God, we just feel like we’re doing a better job if we can be more orderly and/or get things “right.” As if our infinite God might be able to tolerate us just a bit more if we look like we’re trying really, really hard.

But the truth, of course, is that our infinite God is infinite love—God loves us no matter what. Whether we adhere to a strict order in our churches and lives, or whether we’re more welcoming to difference that can sometimes feel like chaos. That kind of welcome can call us out of our comfort zones in ways that don’t always feel good. Stepping away from what feels like order and into the wildness of trust can be hard! But I think, ultimately, this is the work we are called to do.

Excerpt: Sunday Morning Minecraft

by Elrena Evans

Sunday morning, 9 o’clock. As the first notes of the prelude swell out from the church organ, my husband is sitting in the sanctuary with the praise band. My 14-year-old is in her acolyte robe, ready to process with the clergy and choir. My 12-year-old is sitting in the tech booth, where he’s working the church camera for the service. My 7-year-old daughter and 4-year-old son are in Sunday school. And my 9-year-old is sitting in the church library, with me, where he will spend Sunday morning playing Minecraft.

Sunday morning, 9 o’clock. As the first notes of the prelude swell out from the church organ, my husband is sitting in the sanctuary with the praise band. My 14-year-old is in her acolyte robe, ready to process with the clergy and choir. My 12-year-old is sitting in the tech booth, where he’s working the church camera for the service. My 7-year-old daughter and 4-year-old son are in Sunday school. And my 9-year-old is sitting in the church library, with me, where he will spend Sunday morning playing Minecraft.

“Do you want to try going into the sanctuary for Communion today?” I ask him.

“No,” he says.

Church is a particularly challenging environment for my son. And the older he’s gotten, the more of a challenge it has become. A few weeks ago, as he was melting down in the fellowship hall, a well-meaning parishioner looked at me and smiled.

“There’s one in every family!” she said, as she stirred her coffee and walked away.

I looked at her retreating back and thought, Actually? Statistically? There’s not. There isn’t a child like my son in every family.

I know what she means—there’s a “difficult” child in every family—but my son isn’t difficult. My son has special needs. It’s different.

I email a good friend, also the mother of a child with special needs, to vent about church. She suggests we just take some time off—stop trying, stop going for a while. The exhaustion of just trying to get five kids out the door, let alone help my son navigate all the expectations of Sunday morning, is doing me in, and she knows it. She hears about it every week.

I write her back. “I think I would do better at church if people didn’t smile at me. I see all these people, and they smile, and it’s like they’re saying, ‘Isn’t it so great to be here?’ And I want to say ‘Do you see me? Really, truly see me? Because I am dying over here. Please don’t make me feel invisible.’”

. . . .

When my son was a toddler, he loved going to church. What’s not to love? Playground time, goldfish crackers in Sunday school, donuts in the fellowship hall after the service. Sure, he had some trouble controlling his feet and his fists—but many 2- and 3-year-olds do. He could still linger close enough to the middle of the bell curve to avoid setting off alarms.

In our church atrium stands a giant statue of the Good Samaritan helping the injured man on the side of the road. Slightly larger-than- life, featureless figures, the arms of the Samaritan bend around to gently help the injured man as he lifts his head. Mostly, it serves as an indoor playground for kids to climb and swing on. My son was no exception: climbing on the head of the Good Samaritan might have been his favorite thing about church.

One day, my oldest son, then four, started quizzing him on the parable as he swung and climbed.

“What did this man do?” my oldest son asked, patting the head of the injured man.

“Crying!” my toddler son called out, moving to pat the man’s head as well.

“And what did this other man do?”

“Holdin’ hands! Help . . . walk! Care for him!”

Every time I pass the statue I can picture my tiny blond son, sitting there in his puffy blue winter coat, patting the man’s head: “Care for him!”

Things began to shift around the time my son was in kindergarten. Every Sunday, the children’s ministries director would appear at the end of our pew, holding my son by the hand. “He hit one of the teachers,” she would tell me. “He threw a chair. He scratched another child.” This weekly appearance quickly became our new routine, with my son being brought into the sanctuary earlier and earlier each week. Eventually, we couldn’t make it past the opening hymn without my son appearing at our pew. As other children were learning to sit in a circle for Bible stories, sing simple songs, and memorize verses, my son was starting to look more and more like an outlier.

We tried to make it work.

We tried sticker charts, marble jars, rewards, and consequences. We took away screen time. We read more Scripture. Sunday mornings before church I would carefully trim my son’s fingernails (we made time to do this, every Sunday morning, in a house with five kids under the age of 10), and I would talk to him about not scratching, not hitting, keeping his hands to himself.

He couldn’t do it.

A parishioner who works with children who have special needs volunteered to be his “buddy.” We hired a professional aide. The church added sensory items to the classroom and held training sessions for the team of volunteer teachers. But nothing seemed to work.

Our church brought in a representative from Joni & Friends to talk about disability ministries. And that was when I had my epiphany.

“What do you currently do on Sunday mornings?” she asked me.

“We sit in the church library while he plays Minecraft,” I answered, feeling my face redden with shame.

“The Holy Spirit is present in the church library, too,” she said. “God can meet your son there as easily as in the sanctuary.”

So on Sunday mornings, we sit in the library and play Minecraft. With the door open I can hear the strains of music floating up from the sanctuary below; sometimes I drift out into the hallway to listen. The praise band for the later service practices in an adjoining room during the sermon, and I can hear them too. More music and less preaching is absolutely fine by me.

But Communion pulls at my heart. I want my family all in church together, kneeling at the altar rail, receiving Communion every week. I think about the Nicene Creed, our profession of faith that we recite each Sunday: “We believe in the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and the life everlasting.”

Sitting in the church library, watching my son play Minecraft, I am grieving the loss of the communion of saints.

“Do you want to try going in for Communion today?” I ask.

“No.”

“Will you be okay here by yourself for a few minutes if I go down to the sanctuary?”

He shrugs. I decide to take that as an affirmative, and go downstairs alone—cutting the line so I can join my husband and other children as they approach the Communion rail.

But I still hear echoes of my son’s toddler voice as I walk through the church: “Care for him!”

Is that what I am doing? Letting him play Minecraft in the library? And if there were another, better, way to care for him . . . would I know?

A Prayer for Being “That Family”

Dear God, can’t we just catch a break? We see the looks, the sidelong sneers, the covert and not-so- covert judgments aimed our way. When we want to either die of embarrassment or put someone else in their place, help us to remember that we don’t fully know these people or their contexts any better than they know us or ours. Help us to be the bigger person, God. (Actually: scratch that. We are sick of being the bigger person. Please make someone else take a turn for once.)

Amen.

Elrena Evans is the author of Special Grace: Prayers and Reflections for Families with Special Needs (InterVarsity Press). She is also the executive editor of Paper&String, a digital care package celebrating faith, creativity, and beauty in its many forms. She is passionate about disability advocacy, and enjoys spending time with her family, dancing, and making spreadsheets. Watch a video trailer for Special Grace!

This article was adapted from Chapter 4 of Special Grace by Elrena Evans. Copyright (c) 2022 by Elrena Evans. Published by InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL.