Editor’s Note: This post was originally published at an earlier date. We are amplifying voices of Asian heritage for Asian-American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

When he came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up, he went to the synagogue on the sabbath day, as was his custom. He stood up to read, and the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was given to him. He unrolled the scroll and found the place where it was written:

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

And he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant, and sat down. The eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed on him. Then he began to say to them, “Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.”

Luke 4: 16-21

Since my early 20s, as I’ve contemplated Jesus, his ministry, and his invitation to those who would like to be about his business, I’ve returned to this passage over and over again. Growing up in the context of Pentecostal altar calls and public, emotional professions of faith, I’ve often found it easy to look at this passage, to hear Jesus’ reading of the prophet Isaiah, and to assume that it is out of sheer force and willpower that I, too, can live into this anointing of the Spirit of the Lord upon me.

And yet. When I think of those who have followed in the footsteps of Jesus, bearing witness to the family of God and all of its implications on life and the world, I am reminded that to live into Jesus’ proclamation here is not merely a “one big YES, LORD!” proposition, but more often than not it looks like a long, winding trail of little YESes that grow and cost more and more as each new YES is exclaimed.

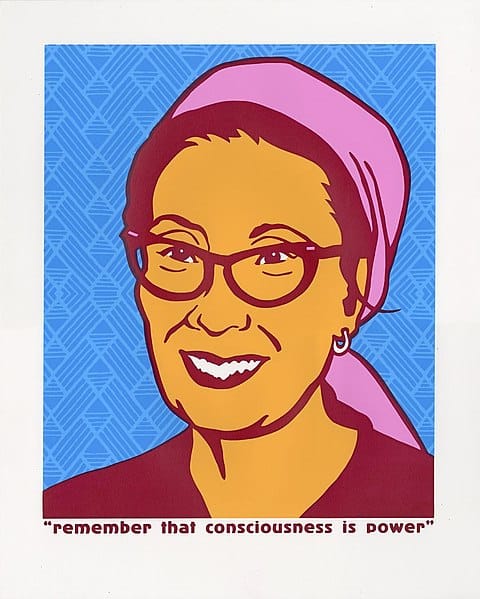

I am reminded of Yuri Kochiyama. I am reminded of how her journey toward radical consciousness did not begin in Harlem but in the mundaneness of her life in San Pedro. Of the sting of racial discrimination, and the eventual uprooting and unjust incarceration of her family during World War II. Of her knack for reporting, and really just showing up, finding the roots of a story even in nondescript suburban situations, covering something as frivolous as sports–a skill set that over time she would lend to her YESes aimed at justice.

I am reminded of how she wrote letters to Nisei soldiers who had been sent off to fight for a country that saw them as the enemy—letters to remind them that though they were out of sight, they were most certainly not out of mind, that even in their absence, they mattered. I think about how this YES for her became an invitation to others to say YES to extending hospitality from afar with thoughtfulness and humanity.

Yuri’s story reminds me that bringing good news to the poor starts by saying YES to just showing up. It’s saying YES to caring about what education is like for your and your neighbor’s kids; it looks like joining your voice and protest alongside your neighbors who can’t find a job because of their race. It looks like saying YES to the “togetherness of all people,” and her constant, willing displacement into the Black community; to movements for Black liberation, causes that she did not see as external to herself but which rather were deeply intertwined with her and her family’s own story.

Each of these YESes, along with the invitations to sleep on her couch, to share a meal or a drink on a Saturday night—she hosted hundreds of young people in her family’s home in the 1950s, saying YES to strangers, indeed, extending family to these people—these are the YESes that snowballed into even grander, more costly YESes as she plunged into her activism and work of solidarity.

While her YESes grew more and more consequential, I am heartened that she was who she was, even as her politics and praxis were radically transformed. She offered up her YESes with enthusiasm and imperfection. Though her hospitality and activism came at great cost to her family and home life, she loved and stretched as fiercely as she knew how, not closing herself off to their critique or invitations to healthier collaboration; she was a mom and a wife who did the best she could.

Back to Jesus in the synagogue: In my younger years, I think I understood most of what Jesus read from the prophet Isaiah—good news to the poor…recovery of sight to the blind, letting the oppressed go free—those things felt obvious to me. I must admit, however, that it wasn’t until much later that I began to understand Jesus being sent to “proclaim release to the captives.” As a young man, I could not understand how captives being set free was a proclamation of good news.

This was obviously indicative of my naïve view of the criminal justice system, as I knew it in my context. I hadn’t yet begun to discern its intertwining with the legacies of race and racialization in our histories. The simple fact lost on me was that some people who were in prison should not have been in prison.

This is the thread of YESes that Yuri chased for decades in her work—political prisoners, unjustly imprisoned. She knew the sting of wrongful incarceration from her own story. That people in the Movement knew to call or write to her and that she always knew who to point them to was breathtaking. Yuri knew her role in the movement in this regard, seeing that the unjust incarceration of political prisoners threatened any material progress made in the Movement at large. This is the same hospitality that she had always extended, but now in a different political register. She was not only advocating for better conditions or the release of the wrongfully imprisoned—she was calling to humanize them in the process: to remember their birthdays, to offer them human interaction when it was scant. This is Yuri, embodying the Good News that Jesus prophetically proclaims in Luke 4.

Even in the height of her political involvement and activism, Yuri never lost sight of people’s humanity. She had the gift of holding complexity at all times—humanity and ideals, whether it was seemingly contradictory notions of revolutionary nationalism, integrationism or separatism, nonviolence and self-defense. Yuri lived out, with humility and earnestness, a life of solidarity and integrity.

In a moment where the prospects of Asian American and Black collaboration can sometimes seem bleak; when it can be easy to assume that the cement of racialization has been hardened, we can look back on aunties like Yuri Kochiyama who moved about the world knowing that the cement had indeed not dried, that true partnership and collaboration is still possible, that the togetherness of all people is necessary for the undoing of white supremacy in our communities and for the true pursuit of justice. The cement has not hardened.

“The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

E. David de Leon is a systematic theology doctoral student at Fordham University and is the Social Media manager for Christians for Social Action. He writes/researches/teaches/preaches at the intersections of Pilipinx/Asian American identity, culture, race, and theology.

E. David de Leon is a systematic theology doctoral student at Fordham University and is the Social Media manager for Christians for Social Action. He writes/researches/teaches/preaches at the intersections of Pilipinx/Asian American identity, culture, race, and theology.