If you want to appeal to people, you need to speak to their concerns—not yours.

Note: Jonathan Haidt is a social psychologist at New York University’s Stern School of Business, examining the foundations of morality and how morality varies across cultural and political divides. He gave the following talk from the main stage at the 2018 CCCU International Forum. It has been edited for length.

I was born and raised in a Jewish family in the suburbs of New York City. I was the sort of kid that was so attracted to science that within two years of my bar mitzvah, I started calling myself an atheist. Not just an atheist, but one of those atheists that sees religion, Christianity especially, as the enemy because [Christians] believe in creationism, and we scientists believe in evolution. Had their books been out in the early 1980s, I would surely have been a New Atheist.

But two things happened that changed me. The first was that I got my first teaching position at the University of Virginia. At UVA, there are a lot of students from the western and southern part of the state. A lot of them are evangelical Christians. I had never actually met evangelical Christians growing up in New York and going to Ivy League schools. They radiated a kind of sweetness, a warmth, gentleness, and humility that I just hadn’t really seen before. It was really beautiful, and it touched my heart. And when your heart is open, then your mind is open.

The second [thing] was my research. I study positive psychology, like the causes of happiness. My first book, The Happiness Hypothesis, has the subtitle “finding modern truth in ancient wisdom.” I read every major work I could find from the ancient world that dealt with human affairs—things from China, ancient Greece and Rome, the Bible—and what I found was that there are 10 ancient ideas that you can discover all over the world that are deeply psychologically true, and that the Bible is among the richest repositories of psychological wisdom ever assembled by human beings. So, the first great truth: The mind is divided into parts that sometimes conflict. Who has ever said that more succinctly than Paul [in Galatians 5:17, discussing the spirit and the flesh]? We are moralistic hypocrites. Again, who has ever said it more powerfully and succinctly [than Jesus in Matthew 7:3-5, speaking of specks and planks in the eye]? We all get it when we see those words.

My second book, The Righteous Mind, is an exploration into why we are so terribly divided by politics and religion. In the course of writing that book, I read a lot of the research on religion. In American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us, a wonderful book by Robert Putnam and David Campbell, they synthesized all the research they could find, and they reached this conclusion: “Religiously observant Americans are better neighbors and better citizens than secular Americans. They are more generous with their time and money, especially in helping the needy, and they are more active in community life.”

I was coming to think of religion in a new way, and as a social scientist, I had to say, “There are many pluses and minuses, and boy, the pluses are quite large and underestimated.” I started realizing that the scientific community at that time was underestimating and misunderstanding religion. I started writing essays for the scientific community saying that religion has been misunderstood and arguing against the New Atheists. I even gave a TED talk on how human beings evolved to be religious; it’s in our nature.

Let me be clear that while my views on religion have changed, I’m still an atheist. But what I’ve come to realize is that we have a very important belief in common. It is that there is a God-shaped hole in the heart of each man. Now I happen to believe that came about as a product of natural selection; human beings evolved with religions that gave us a moral order, that gave us civilizations. Many of you don’t agree with that—and that’s okay. One thing that we are learning in our incredibly divided country is that we have to look for agreement where we can find it, and we have to find ways to live with people who disagree on certain things if they agree with us on other things that matter.

Where our values divide—and overlap

If there is a God-shaped hole in everyone’s heart, regardless of how it came about, then it matters how that hole gets filled. And if you fill it with good stuff—if you fill it with values of service, decency, responsibility, and caring for your family and for others—then things will go well for those people, their community, and their country. But if you fill it with garbage—with materialism, with petty motivations—then things will go badly.

As far as I can tell, Christian colleges do a good job of filling that hole and training students not just in the facts but in virtues. You do a lot more for moral education than we do at secular universities, and a lot of that moral education is for humility, self-control, a sense of service, and serving others before yourself. Boy, are these virtues that we need more of in this country at this time. In fact, an issue that I’ve been very concerned about these days is what’s going on at the secular universities. And it seems as though this God-shaped hole is being filled with a particular kind of political activism that I think is bad for students themselves, for the universities, and for our country.

So I want you to be successful in your mission for moral education. I know you’re in a difficult situation in this culture war, and obviously it’s impacting certainly all of you who are from the United States. So what I’m about to say is about what’s going on in the United States, but all of you operate in a very complicated political space, I’m sure. And things that happen in the United States often spread; our trends do tend to go to many other countries.

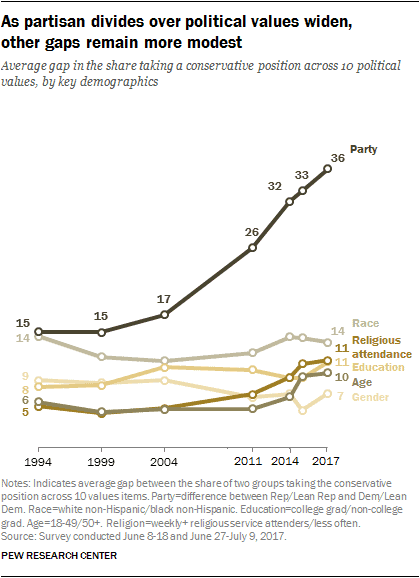

The Pew Foundation has been asking a set of questions now and then since 1994, and there are 10 items that they have been asking about repeatedly. So think of it as a basket of opinion items. They take different groups, such as by gender, and measure the difference on these 10 items. In 2004, men and women were about eight points apart; in 2017 they’re about seven points apart, so no change. Men and women are not any more different in our attitudes than we were 10 or 20 years ago.

And that’s generally true for all of those things with two exceptions: Religious attendance and political affiliation. In 2004 Americans who went to a [religious service] regularly were not very different from those didn’t. But by 2017 the gap had more than doubled. So we are coming apart by religion. But that’s a small increase compared to the growing split by political party; that gap has also more than doubled so that on average, there is a 36-point difference between the left and the right. We are coming apart. The left hates the right. The right hates the left. We’re different kinds of people on the two sides, and we increasingly cannot compromise and we cannot live together. It’s a disaster.

And that’s generally true for all of those things with two exceptions: Religious attendance and political affiliation. In 2004 Americans who went to a [religious service] regularly were not very different from those didn’t. But by 2017 the gap had more than doubled. So we are coming apart by religion. But that’s a small increase compared to the growing split by political party; that gap has also more than doubled so that on average, there is a 36-point difference between the left and the right. We are coming apart. The left hates the right. The right hates the left. We’re different kinds of people on the two sides, and we increasingly cannot compromise and we cannot live together. It’s a disaster.

Let’s talk about what you can do to survive in this incredibly polarizing world. My book, The Righteous Mind, describes three principles about moral psychology. And if you understand these, you can use these and apply them in any complicated situation.

The first basic principle is that intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second. Here’s how to understand that. That first truth I told you about before—that the mind is divided in parts that conflict—every society knows this. Plato and the Western tradition gives us the idea that the mind is divided like a charioteer—reason—who struggles to control the passions. But my research has brought me to agree with the philosopher David Hume, who said, no, it’s the opposite. Reason is and ought only to be the slave of the passions and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.

But reason is not so much a servant like a butler; it’s really more like a press secretary of everything else in your mind. We are really good at reasoning not to find the truth but to defend ourselves and reach the conclusions that we want to reach. The basic rule is that when someone says something, you have an instant gut feeling: You want to believe it or you don’t want to believe it. If you want to believe it you say, “Can I believe it? Do I have permission?” If you don’t, you ask, “Must I believe it?” So we’re asking two different questions. We’re always asking one but not both.

Now think about everything we argue about in this world. Is there anything that is totally unambiguous? You might think so, but believe me, other people think not. All of these moral social issues are ambiguous. We can see what we want to see. This is why we cannot persuade each other with logic, reasons, and evidence. Once emotions and group concerns come into play, you cannot persuade people with reason alone. You have to speak to the emotions and the intuitions first.

A metaphor I use is the mind is divided like a small rider on a large elephant. The reason is the rider. If you just speak to the rider, there will be no change. You have to change the elephant. You have to build trust and relationships, and you have to appeal to what we share with common humanity. The greatest oratory in our history tends to be that which is, yes, making an argument, but it’s all wrapped in beautiful metaphor and appeals to common humanity. Our great orators speak to the elephant while also giving material for the rider.

Six named foundations of morality

The second basic principal: Speak to the intuitions. Well, what are intuitions? My own research has been on the theory that my colleagues might call Moral Foundations Theory. What is it in human nature that makes us respond to events in the social world? Our conclusion is that there are six named foundations of morality.

The first is care and harm. We’re mammals; being a mammal means our brains and bodies evolve to care for and nurture. And this is a big foundation of morality, especially on the left—caring, compassion. The second is fairness and cheating. Every society cares a lot about fairness; every society is very concerned to catch cheaters. The third foundation is liberty and oppression. Nobody wants to be constrained or controlled. We rebel against that. The fourth is loyalty and betrayal. We form groups, and we hate people who betray our groups. The fifth is authority and subversion. We have built into us ways of responding within a hierarchy. The last is sanctity and degradation, which has no analog in the animal kingdom. These are unique to human beings. They play huge roles in sexual morality but also in food and things like that.

When people register on my research site, YourMorals.org, those who say that they are very conservative get high scores on all of the foundations of morality. But people who say that they’re very progressive, they value care and compassion the most, and they say that loyalty, authority, and sanctity are not part of morality. They reject those. And so this sets us up for the current American culture war. Everybody uses care, fairness, and liberty; although they use them in slightly different ways, everyone uses them. But when it comes to loyalty, authority, and sanctity, those are much more widely used on the right than on the left.

If you want to appeal to people, you need to speak to their concerns—not yours. Research is showing that if you put people in discussion, they spontaneously throw at the other person the things they care most about. But if you say, “Well, how about trying to speak to what they care about?” They can actually do it, but they don’t think to do it without prompting.

Obviously, you’re wrestling and adapting to changes around LGBTQ, and I was pleased to see on the CCCU website, and in some of the online essays I found, that the CCCU is working on the issue of how to change, how to adapt, how to welcome the LGBTQ community within the doctrinal constraints you have. I was pleased to see various authors using the language of fairness, care, and protection. So that seems like a very positive sign to me.

The power of collaboration, apology, and concession

The last of the three principles: Morality binds and blinds. I believe we have evolved this particular morality to bind us into groups that are effective at competing with other groups. Many social scientists are fascinated by large-scale cooperation. How does it happen that you get lots of individuals cooperating? In the animal kingdom, the only way you get it at large scale is if they’re all children of the same female. They’re all siblings; they are all in the same boat genetically. The only species that can do large-scale cooperation without kinship is humans.

Interestingly, whenever you find civilization breaking out on earth, you always find temples first. Once you get agriculture and a little surplus, you get temples. Religion plays an enormously important role in early agricultural societies. The trick that we have is that we can circle around a sacred object, and it’s like we’re generating an electric charge. It doesn’t have to be a religious object. We do it for lots of things. We do it for a flag. We treat the flag as sacred. Then you fight together as a team; your buddies are bound together.

But while we did that in World War II, after the war, what James Hunter, a sociologist at UVA, noticed is that the country was dividing so that the orthodox wing of each religion was teaming up with each other against the progressive wing of each religion and the secular societies as well. This was becoming the new culture war, as he said in his 1992 book, which is still extremely relevant today. He draws on the sociologist Émile Durkheim, who noted that “Communities cannot and will not tolerate the desecration of the sacred. The problem is this: Not only does each side of the cultural divide operate with a different conception of the sacred, but the mere existence of the one represents a certain desecration of the other.” We cannot tolerate the existence of the other side.

So sacred value problems are incredibly difficult, but there is some good research on it. I would recommend to you the work of Scott Atran, an anthropologist who looked at sacred value conflicts among Israelis and Palestinians, and with suicide bombers. His general finding is that sacred values are not practical; they’re not trade-offs. So if you try to say, “Well, okay, how about if you guys give up the land, but we give you huge amounts of money so we can have a society there,” that doesn’t help—that makes them angry.

What Atran says is that better than any sort of practical inducement is a symbolic concession. Make an apology that acknowledges the legitimacy of their sacred value, and do something that is painful for your side. When you do that, the other side suddenly becomes much more willing to give. The implications here are that all political movements hold something sacred. That’s what brings people together, so they can fight together against someone else. Know what their sacred values are and try very hard to respect them.

Furthermore, to resolve sacred value conflicts, acknowledge that you have done something wrong. Start that way. Do something that acknowledges that you see the legitimacy of their sacred value and you make a concession to them that is a symbolic concession.

If you can do that, suddenly they become much more willing to negotiate, much more willing to be flexible themselves. This advice is obviously very good advice; Jesus said it, too. When you have a conflict, start with yourself. Start by pointing out what you got wrong. Start with the log in your own eye. Then you’ll be able to talk and communicate and make progress.

Jonathan Haidt is a social psychologist at New York University’s Stern School of Business, examining the foundations of morality and how morality varies across cultural and political divides. This article was adapted from a talk he gave from the main stage at the 2018 CCCU International Forum. It originally appeared in print in the Spring 2018 issue of Advance, a publication of the Council for Christian Colleges & Universities, and is reproduced here by kind permission of the editor.