Editor’s Note: This post was originally published Jun 27, 2019. Since then, the organization we interviewed has changed its name to Right to Be.

Editor’s Note: This post was originally published Jun 27, 2019. Since then, the organization we interviewed has changed its name to Right to Be.

“Hey, baby, come over here and let me look at you a minute.” “Smile, beautiful.” “What’s your name, little mama?”

I never know what to say when I hear this kind of stuff while walking down the street. My first thoughts are “Who is this guy? What is he saying?” and then “Does he think I feel flattered by it? Does he think it’s going to make me feel like stopping and talking to him?”

It makes me feel like a product being auctioned at a street market. But what can you do? Like most women, I walk on, accepting both the experience and my discomfort as “just the way it is.”

But that phrase has never sat well with me—and it has not sat well with Erin Filson either. Erin Filson, author of the quirky online comic “The Adventures of Ranger Elf,” has joined the ranks of many talented artist-activists on the subject of street harassment. Filson also served as the creative director for the Philadelphia branch of the nonprofit Hollaback. I had the privilege of sharing gelato and coffee with Filson in Philadelphia, and learned all about Hollaback’s work and the comic book Filson created to address street harassment.

What can you tell me about your comic book , Hollaback: Red, Yellow, Blue?

, Hollaback: Red, Yellow, Blue?

Filson: This comic was a collaboration between myself and Hollaback’s Rochelle Keyhan and Anna Kegler to educate and inform people in an accessible way about street harassment. We’ve had a lot of fun going to different comic conventions to show the book and also to do research into the way harassment happens. We cannot ignore or absorb harassment as something that is “just a part of our experience.”

Tell us about the mission of Hollaback.

Filson: One of the main missions of Hollaback is to start a conversation. It’s not to require you to turn around and yell at someone who harasses you. A lot of people aren’t comfortable saying anything, or it happens so fast that you don’t know what to say. It’s such a weird situation. Most of the time you’re on your way somewhere, and you’re not expecting it, and it happens, and what are you really supposed to say? I mean, do I turn around and say, “You! I’m going to write a comic about you!”? It’s so accepted and normalized. So Hollaback starts these conversations to show that street harassment is a real thing, and it makes people uncomfortable, and it’s not okay to objectify people. This helps educate ourselves and educate others.

Harassers tend to justify what they do as simply “flirting.” How would you explain the difference between street harassment and flirting?

Filson: My personal stance is that harassment is whatever makes you uncomfortable—it shouldn’t be tolerated even if it is posed as “flirting.” But I think street harassment is a little bit more aggressive. The usual scenario is something that’s shouted out from across the street; it’s anonymous and dehumanizing. You can usually feel the difference. Of course, it’s up to you how you respond. Hollaback doesn’t want to encourage you to put yourself in a dangerous situation or to respond in a way that makes you uncomfortable. But that’s why you can use Hollaback as a resource to sort some of this ambiguity out. If you’re uncomfortable, it’s okay to not accept it. Women are often taught to be friendly and just accept attention like that—or taught that it’s safer not to reject it and risk a negative reaction from the man—but it’s okay to draw a line for what you will and will not accept.

What started this journey for you with Hollaback?

Filson: Well, I always liked to draw, make up characters, and play imagination games. As I child I would go through my coloring books and draw bows and eyelashes on all the people and animals because I thought, “There aren’t enough girls in here.” So even at a young age I could recognize when women weren’t represented. I grew up really loving comics and continuing to work on creating art. Then, I went to the Jubilee Conference during my senior year at University of the Arts, and I heard about human trafficking for the first time. That’s when the idea of combining art and social justice kicked in.

After school I was searching for employment and was already thinking about creating a comic that talked about the experiences my friends and I had with street harassment. I ended up getting connected with Rochelle at Hollaback, and it was really amazing because we all had needs that met in the middle. They needed someone to come in and help them conceptualize some SEPTA [public transportation] ads at the time, and they gave me such great freedom—which is so rare in the creative world—to collaborate and make not only the ads but also this comic. So I had the freedom to see these ideas come to life the way I envisioned them, and now I’m their creative director!

I don’t want to say that street harassment is as bad as human trafficking, but both are seeing people as property and dealing with gender issues. (Hollaback has actually done a few events about trafficking and raising awareness about it in the states, showing that it’s also a problem here.) But I enjoy making art for this defined reason.

What kind of feedback has the comic book gotten so far?

Filson: We’ve gotten some really great feedback from people, especially guys. A lot of people want to support it, and when we explain what we’re about most people are onboard with it. By the time we explain who we are and share about the comic, so many people are like, “I’m buying one. Thank you.”

What’s your creative process like? Do you start with a message?

Filson: It depends on what I am doing. Doodling is my favorite art form. When I’m doing that, there’s generally not any sort of thought behind it. But with things like this comic, there is obviously a message behind it. I am going to be in a show in January that deals with modern-day slavery. It’s such a dark, crushing issue that it’s hard to sit down and do it justice and show how much it matters. I’m really stuck on that. So, if you have any ideas…

How do you process all these “dark, crushing” issues?

Filson: I think the problem we share as people is that we generally don’t want to deal with those issues. We tend to numb ourselves with shopping, working, complaining about our jobs and everyday lives. It becomes, “Oh no! This person broke up with me, and Starbucks ran out of half-and-half, and I wish I could find a job with more autonomy…” But these are the things that are right in front of us. They’re safer and easier and much more socially acceptable to deal with because we don’t know how to honestly deal with bigger issues.

Art in general is supposed to jumpstart people out of everyday thinking and show other possibilities and avenues of thought. It helps us find avenues to deal with things we may not normally deal with. Art exercises parts of your mind that you don’t normally play with and stretches and grows you. God is a creative artist who makes some weird stuff that’s all really cool, even stuff that doesn’t seem to make sense—like water bears. Water bears are these little micro-animals that live on moss and are basically indestructible. They can go to space, live through nuclear warfare and super-hot and freezing temperatures—but they quickly die if you put them under a microscope under a glass slide (they get crushed). I think the same is true for art.

Art for me is also a really great way to work hand-in-hand with organizations and groups that are trying to radically change the world. This is not to say that I don’t get flustered or feel like “Oh, God. What am I supposed to do?” I get emotional and angry and then go cook dinner and have to go to bed and to work the next day. I wake up thinking, “Oh, I’ll do this better” or “I’ll go talk to this person.” I wish I knew exactly what to do and could say, “I’m going to go out and end slavery!” But I can feel so small and powerless and revert to struggling again with those everyday things.

But that’s what I like about superheroes, because often their normal lives are kind of crappy, but they have to rise above that and do more because they have a greater calling. You could argue that we have a greater calling, too.

Who’s your favorite superhero?

Filson: Well, I love Rogue from X-Men. I have always loved her because she was the first woman superhero I encountered who didn’t take any sass from anyone and could just throw things. I mean, I never liked the Invisible Woman, because that was a dumb power for a woman. And lots of female characters had only the defensive powers or were the girlfriend. They were never quite the powerhouse brawler that I finally met in Rogue.

If you could have any superpower, what would it be?

Filson: Super-strength. I think it would help my anxiety about doing certain things, and talking to people.

And dealing with street harassment?

Filson: Exactly! But I would use my powers responsibly, of course!

What do you believe needs to happen in order for street harassment to end?

Filson: I think only some people know about it or know that it’s actually a problem. So just making the term “street harassment” more common and educating more people about it is a start. We’re raising awareness, starting conversations, and showing the emotional and societal effects of it. I think it needs to be treated more seriously than it has been because it’s linked to so many issues with the way women are portrayed—on TV, in video games and comics, etc.—and the ways we’re taught to interact as men and women.

Sometimes humans don’t know how to interact with each other appropriately; we don’t know what others are expecting or thinking. So that has to be healed continually, on a daily basis, in small and big ways through being willing to sit down in a real conversation and talk about what we really go through. But I think it begins with awareness—not falling into the “that’s the way it is” trap—presenting a healthy alternative way of interacting with each other.

Jennifer Carpenter is a former Sider Scholar.

Check this out:

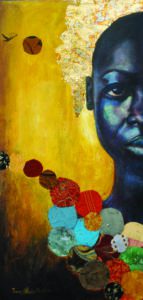

Stop Telling Women to Smile is another project where artists put their creativity toward the cause of ending street harrassment.

10 Hours of Walking as a Woman in NYC is a telling reminder of what many women endure.

Smile offers a more comic but no less poignant look at the problem.