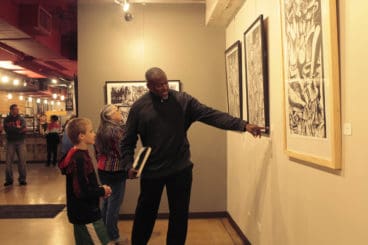

Artist Steve Prince is a tower of affability. At 6′ 6″ he stands about half a foot taller than most people in the room, but despite his height, he is earthy and grounded. As he greets people, his eyes light up and he talks to each one like they’re the most important person in the room. And as a crowd mills about his prints—linoleum cuts, woodcuts, and lithographs—he’s asking them questions about what they see, what catches their eye, what the symbols might mean to them.

A boy of about 10 years old is in front of one of his pieces, and Steve engages him in conversation. Steve asks the boy to read the print to him, while pointing to different parts of the work. People start gathering around to watch the two interact, Steve as animated as the boy is still, slightly nervous in the spotlight.

Steve is encouraging him along, praising his interpretation, giving him claps on the back and high fives for his insightful responses. When they have exhausted the meaning of the piece for now, the encircling audience hoots and claps for them both, and the boy smiles shyly as Steve laughs and claps, too.

We move to the small, black-box theater where Steve is going to talk about his art. He has a PowerPoint presentation cued up on the screen, but first leads us in a rousing chorus of the “Victory Chant” (Hail, Jesus), complete with stomps and claps.

Steve shares about his childhood in New Orleans and then goes on to explain the bamboula, or circle dance, that comes out of Africa and was performed in Congo Square when the slaves had an opportunity to be together to mourn or celebrate:

“I have been utilizing the funerary traditions coming out of New Orleans as the foundation of my work. The jazz funeral is broke down into two parts: The first part is called the “dirge,” the mournful tune that is being played as the person is laid to rest. The musicians were literally playing music to make you mourn, cry out, express, to get it all out of your system. This is no time to be holding it back. After that, the music moves from mournful to celebratory, which is called the second line. The first line is the family of the person being laid to rest. The second line is the community. The first line is the life here on earth, the second line is the afterlife.”

The first line is the family of the person being laid to rest. The second line is the community. The first line is the life here on earth, the second line is the afterlife.

Steve plays a mournful jazz dirge and models the march and sway of the funeral procession. The second line jazz comes next: an upbeat tempo with drums and horns. He dances across the stage with joy.

I had the pleasure of interviewing Steve before his opening reception in Chicago, and the joy that radiates from him on stage is the same joy he radiates when he speaks of his art, his convictions, and his calling.

Tammy Perlmutter: How would you respond to someone who thinks you should focus more on the positive aspects of the African-American experience?

Steve Prince: I deal with some of the hurts and pain, but I also deal with the triumph and the resistance; the creativity, the imagination. Which are those things specific to African-American culture—the survival, the retention of so much history, things from the past that have been passed on. That’s why I called my show Sankofa. Then I also termed the show Rebirth, which goes right into the idea of the dirge, that second line I spoke of.

There are a lot of scars of our pasts. As we know, we can’t gloss over those scars and act like happiness is going to replace all that. You have to get at the root of it, you have to go down to the foundation, that’s why Christ says you have to be reborn. That’s the root. That’s the beginning.

I see a lot of familiar patterns right now. To have a Trayvon Martin or a Michael Brown or an Eric Garner dying in this temporary context in less than ten years—it’s no different than hearing about what happened to Emmett Till, Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, or Huey Newton. How many countless others were lynched all across the South, across the whole United States? As a Christian artist I look at it through the eyes of Paul. He says we battle not against flesh and blood but against principalities. I believe that’s what we’re fighting against: those things that are operating in high places. My work is waged against that.

I see a lot of familiar patterns right now. To have a Trayvon Martin or a Michael Brown or an Eric Garner dying in this temporary context in less than ten years—it’s no different than hearing about what happened to Emmett Till, Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, or Huey Newton.

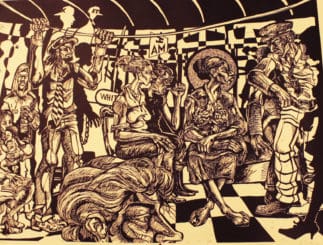

Tammy Perlmutter: You employ a design mechanism called dense pack. What is that, and how is it effective for your message?

Steve Prince: Dense pack is a design tool where I pack a lot of things into a small space. It’s hard for the viewer to take it all in; it’s like a song with many instruments. There’s a melody. There’s structure. But when you listen to that song one time you hear that bass. You listen again you hear that treble. You listen another time and you hear another instrument, you hear that other harmony, hidden underneath the tunes and the sounds. So it’s like poly-rhythms; or in my context as an artist it’s a poly-narrative. My work is layered with story on top of story on top of story.

Dense pack forces you to slow down; you have to sift through the image. But the image has what is called a slow-time response—you end up seeing new things over time. I’ve had people call me up years later and tell me they found something they had never seen before!

It’s my hope that we think of the dirge differently, not necessarily related to a funeral, [but] rather thinking of it as those things we have to deal with on a daily basis. If we’re going to get to a second line, we’ve got to go through a dirge, and we have to go through it together. That’s where I’m drawing from Sankofa, it’s looking back with the hope of us moving forward, together.

Steve Prince’s art is on exhibit through November 28 at Wilson Abbey in Chicago.

Tammy Perlmutter writes about unabridged life, fragmented faith, and investing in the mess. She is founder and curator of The Mudroom and co-founder of Deeply Rooted, a biannual worship and teaching gathering for women. Tammy is a member of Redbud Writers Guild, writing blog posts, personal essays, flash memoir, poetry, and even preaching sometimes. She’s an urban beekeeper and lives in an intentional Christian community in Chicago with her husband, Mike, and daughter, Phoenix.

Tammy Perlmutter writes about unabridged life, fragmented faith, and investing in the mess. She is founder and curator of The Mudroom and co-founder of Deeply Rooted, a biannual worship and teaching gathering for women. Tammy is a member of Redbud Writers Guild, writing blog posts, personal essays, flash memoir, poetry, and even preaching sometimes. She’s an urban beekeeper and lives in an intentional Christian community in Chicago with her husband, Mike, and daughter, Phoenix.