(Editor’s Note: As detention and deportation escalate, families like Yeonsoo Go’s reveal the human cost of current immigration policies. Here, Caleb and Sam examine why the Christian practice of sanctuary matters now — and how churches have historically responded when the state became the threat. We are also offering an exclusive downloadable Sanctuary Starter Packet that includes theological foundations, historical insight, and practical next steps for faithful engagement.)

In July 2025, Yeonsoo Go, a 20-year-old college student, checked into the Manhattan ICE office with her mother, an Episcopal priest from South Korea, for a routine conversion of her visa status from religious dependent to student.

To their shock, ICE arrested Yeonsoo in front of her mother immediately after her hearing and detained her without explanation.

After two days, they transported her from New York to Louisiana. The Episcopal Diocese of New York, the Interfaith Center of New York, the New York Immigration Coalition, and her church immediately began protesting her arrest on the streets and praying for her release daily.

ICE finally set Yeonsoo free, without apology, after five days.

When the State Becomes the Threat: Why Families Need Sanctuary Today

As President Trump escalates mass detention and deportation, families like Yeonsoo’s fear kidnapping, as children who came with caregivers risk separation, detention, and removal to countries they never knew. As innocent family members facing unjust persecution, they need critical support and protection by churches.

They need sanctuary.

For Christians, sanctuary has long been defined as a place of refuge for the vulnerable, including the resident alien and sojourner (Josh. 20:9). American churches have also historically harbored those fleeing slavery and danger, even when it meant defying the law. Between roughly 1820 and 1860, churches served as integral stations in the Underground Railroad network that freed Black slaves.

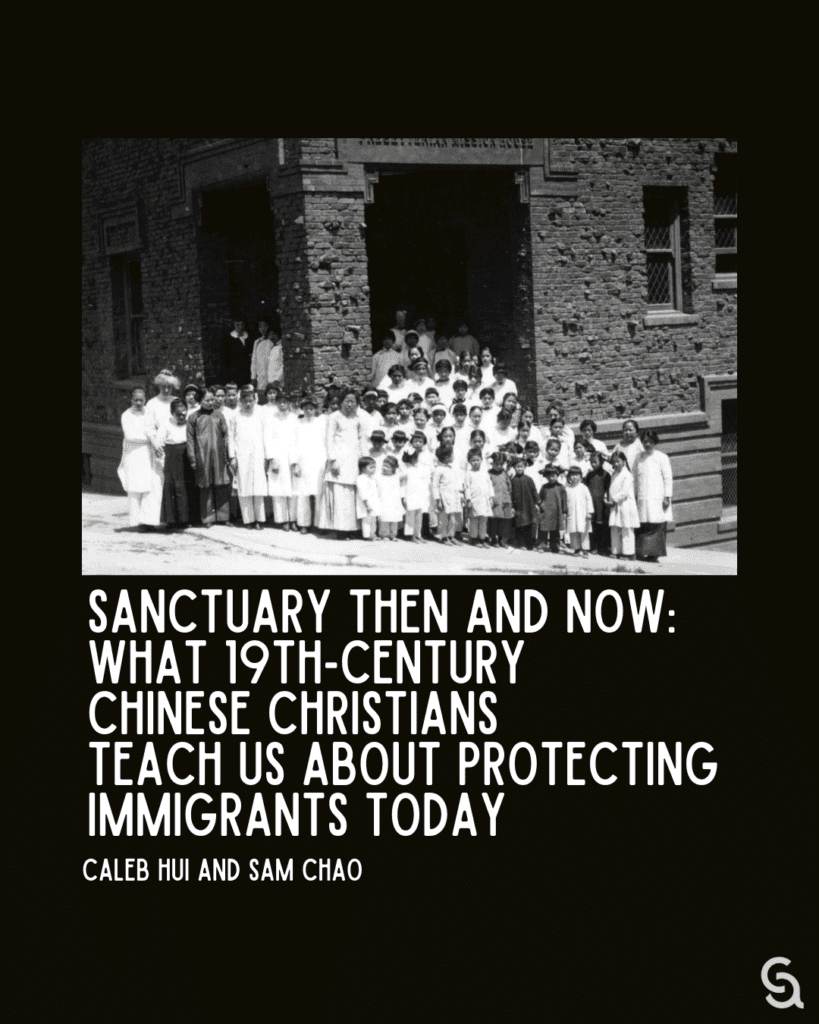

Historic Models of Christian Sanctuary: Rev. Jee Gam and the Women of Cameron House

Likewise, two examples from the Chinese American Church in the 19th century — Rev. Jee Gam and Cameron House, a Presbyterian mission home — offer us models of sanctuary needed today.

A Chinese minister, Jee Gam (1849-1910) not only preached equality for Chinese Americans and justice for immigrants, he also took concrete actions to secure their rights and freedom.

At the risk of his own safety, he opened up his family’s home in 1887 to Ah Yung, a Chinese girl sold to traffickers by her mother. Rev. Gam offered care and protection even though the Chinese Six Companies, a powerful association in Chinese American immigrant communities, had threatened to kill another man who helped her to escape.(1)

Furthermore, Rev. Gam rallied Chinese American Christians to engage in civil disobedience against unjust laws targeting Chinese migrants.

In response to the Geary Act (1892) that extended Chinese Exclusion and required Chinese in the US to register for photo identification cards or be deported, Rev. Gam encouraged fellow migrants to defy the government. He criticized the law for infringing on Chinese people’s “sacred rights…in the Declaration of Independence declared to be inalienable.”(2)

Denouncing the act as “un-American, barbarous… inhuman…[and] unchristian, for it is contrary to the teaching of Christ,”(3) Rev. Gam encouraged Chinese Christians to join the largest act of immigrant civil disobedience in American history. If he were to witness the kidnapping of Yeonsoon Go today, he would decry it as immoral. In the same vein, he would name this administration’s policies for mass deportation, racial profiling, and family separation as contrary to the teaching of Christ.

As Jee Gam called for civil disobedience and sanctuary protection in response to the teachings of Christ, Cameron House, a Presbyterian mission for women who had been trafficked, likewise held America to higher moral standards and provided sacred space and protection for vulnerable Chinese women.

Despite a rescue discourse that was paternalistic, Cameron House acknowledged, in its mission statement, the need to rectify moral wrongs:

“To free Chinese girls and little children from cruel and degrading slavery; to prevent orphan girls from being sold; to give these unprotected, friendless ones the love and care of a Christian home.”(4)

In the 1870-1980s, at least 50 percent of the roughly 4,000 Chinese women in California were trafficked, often in their teens.(5) Under the leadership of Donaldina Cameron, Cameron House aided over 3,000 of these individuals in escaping their brothel owners and protecting them from recapture by gang members.

Wong So is one individual who found sanctuary at Cameron House.

In 1922, her mother tricked her by arranging a fake marriage and instead sold her to a brothel owner who trafficked her to the US. Wong’s brothel owner treated her poorly, threatening her at gunpoint when she did not earn enough money. Knowing her owner had committed three homicides, Wong feared for her own life.(6) She faced constant pressure to support her family financially in China and perpetual surveillance by her owners, recalling, “I was very miserable and unhappy.”(7)

Desperate in the sex trade and without proper documents, Wong escaped to Cameron House. There, she learned to read and write English and Chinese, converted to Christianity, married, and started a family. Eventually, Wong gained the financial means to help raise her sister and brother-in-law’s son. Wong’s own daughter, Mae, graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in bacteriology.

Carrying on Cameron House’s legacy, Wong herself adopted a girl who had been prostituted.

Cameron House workers stood in solidarity with the Chinese American girls who had been trafficked, despite the dangers involved. Chinese brothel owners attacked Tien Fu Wu, a Chinese co-director at Cameron House, calling her a prostitute and “stinking sow” and declaring that “negroes, dogs, and thunder” would come after her.(8)

Nonetheless, Wu held to her convictions of providing sacred protection for vulnerable immigrants.

Carrying the Legacy Forward: How Churches Can Offer Sanctuary Now

Today, across the country, our own very government and its agents are the ones doing the trafficking. ICE horrifically kidnaps and disappears immigrants and asylum seekers.

Learning from the models of Rev. Jee Gam and Cameron House, we too must take risks in following our convictions and joining sanctuary congregations across the nation that:

- provide housing, funding, and protection for immigrants, as Jee Gam did for Ah Yung;

- support respondents at immigration hearings, as Tien Fu Wu and other Cameron House workers did for trafficked Chinese women;

- stand vigil outside court houses in solidarity, as churches did in protest of Yeonso Go’s arrest.

The author of Hebrews calls Christians to stand with the mistreated and those being detained as though we ourselves were suffering with them (Heb. 13:3).

As our spiritual ancestors have protected the vulnerable, may we also heed Jee Gam’s call to uphold Christian values of equality and justice through mercy and sanctuary for immigrants today.

Endnotes:

(1) The American Missionary. “Imperium in Imperio.” Vol. 41, no. 8 (August 1887). Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/57107/pg57107-images.html

(2) Jee Gam, “The Geary Act: From the Standpoint of a Christian Chinese (1892),” in Chinese American Voices: From the Gold Rush to the Present, eds. Judy Yung, Gordon H. Chang, and Him Mark Lai (University of California Press, 2006), 89.

(3) Ibid.

(4) Donaldina Cameron, “Rescue Work of Occidental Board,” Women’s Work 26, no. 1 (January 1911), 12.ik

(5) Judy Yung, Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (University of California Press, 1995), 29, 41.

(6) Wong So, “Wong So’s Story,” cited in Donaldina Cameron, “The Story of Wong So,” Women and Missions 2, no. 5 (1925), 170.

(7) Wong So, “Wong So’s Story,” 171.

(8) Rae Alexandra, “The Child Slave Who Helped Rescue Thousands of Women in Chinatown,” KQED, May 21, 2020, https://www.kqed.org/arts/13880286/the-child-slave-who-helped-rescue-thousands-of-women-in-chinatown.

Ready to go deeper?

Download our exclusive Sanctuary Starter Packet, designed to help individuals, groups, and congregations engage this moment with Scripture, history, and practical guidance. Included are biblical foundations, reflection questions, and concrete next steps.

____

C

C aleb Hui is pursuing a degree in Political Economy and a minor in Data Science at UC Berkeley. Raised in the San Francisco Bay Area, his research interests focus on Asian American Christian and education equity issues. Caleb is currently a member of Resurrection Oakland Church in Oakland, California, and intends to pursue a career dedicated to education policy following graduation.

aleb Hui is pursuing a degree in Political Economy and a minor in Data Science at UC Berkeley. Raised in the San Francisco Bay Area, his research interests focus on Asian American Christian and education equity issues. Caleb is currently a member of Resurrection Oakland Church in Oakland, California, and intends to pursue a career dedicated to education policy following graduation.

Samuel (Sam) C. Chao is studying Psychology and Religion at Emory University. Born and raised in North Potomac, Maryland, Sam is deeply formed by the Chinese immigrant church he grew up in, Chinese Bible Church of Maryland (CBCM). His research focuses on Chinese American Christianity through the lens of race and religion, which he aims to pursue in graduate studies. He currently attends Christ Covenant Presbyterian Church (CCPC) in Peachtree Corners, Georgia.