“I saw dried blood on the jagged edge of the blade. She spat on it and wiped it against her dress… The next thing I felt was my flesh, my genitals, being cut away. I heard the sound of the dull blade sawing back and forth through my skin.”

“I saw dried blood on the jagged edge of the blade. She spat on it and wiped it against her dress… The next thing I felt was my flesh, my genitals, being cut away. I heard the sound of the dull blade sawing back and forth through my skin.”

“They see it as an act of love, they see it as preparing their child for adulthood.”

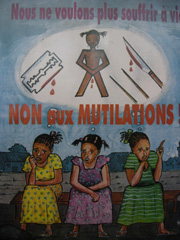

Controversy surrounds the custom of female genital mutilation. Even the name itself has been the subject of dispute: Circumcision? Cutting? Mutilation? Western physicians attending to circumcised women in the 1970s quickly decided that “circumcision” did not nearly describe the practice. Activists argue that “cutting” also implies a simpler procedure and result than the procedure often entails, yet for those whose traditions require it, “mutilation” indicates Western judgment of a misunderstood custom. For the purposes of this article I shall refer to it as female genital mutilation (FGM), in line with international legal norms and the increasing number of women from practicing cultures who have become advocates against it.

The World Health Organization (WHO) definition states: “Female genital mutilation comprises all surgical procedures involving partial or total removal of the external genitalia or other injuries to the female genital organs for cultural or non-therapeutic reasons.”

They classify four types of FGM:

Type 1 — Clitoridectomy: partial or total removal of the clitoris and sometimes the prepuce (clitoral hood).

Type 2 — Excision: partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora (the labia are “the lips” that surround the vagina).

Type 3 — Infibulation: narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal, formed by cutting and sewing together the remainder of the outer labia, with or without removal of the clitoris.

Type 4—Other: all other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, e.g. pricking, piercing, incising, scraping, and cauterizing the genital area.

The age at which FGM is performed also varies. In Ethiopia, it is soon after birth. Elsewhere it is shortly before marriage. Generally, however, girls are operated on between the ages of 4 and 14.

FGM is practiced in 28 African nations, some Middle Eastern nations such as Yemen, and in other parts of the world, such as Indonesia. While it is not a requirement of any major religion, it is performed on girls from Muslim, Christian, and Jewish communities.

The practice affects 100-135 million women and girls who have already been operated on, and a further 2-3 million more each year. That’s 6,000 to 8,000 per day, or up to six girls per minute.

Immigrants in Western nations sometimes bring the practice with them: The African Women’s Health Center at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston used the 2000 Census to estimate that 228,000 women in the United States either have had FGM or are at risk, and the number has risen 35 percent since 1990. Canada, Europe, and Australia have similar statistics, and report girls being taken back to their nation of origin to have FGM performed during school vacations.

Records of FGM being practiced date back at least 3,000 years. Its origins lie in ensuring female fidelity and thus paternity confidence (infibulation,Type 3, creates a “chastity belt” of scar tissue across the vaginal opening). It slowly became a matter of family honor, ensuring virginity and therefore marriageability.

Many of these beliefs still stand, alongside others. Meanings are added as time goes by — something which is a symbol of purity and honor can quickly become seen as aesthetic too. Myths about FGM include that it makes a woman smell more attractive to her husband, that it is necessary for hygiene and health, and, more recently, that it prevents HIV transmission. In a culture where every woman has a particular type of FGM performed on her, there is no way to know what healthy, intact female genitals are actually like: “Excision is our tradition. The clitoris grows long if we don’t remove it, like the male part. In order to be clean and to wash yourself it must be removed. I’m told that in Congo, women hang weights on that female part until it grows as long as an elephant’s trunk!” an elderly woman in Mali, West Africa, told the Independent.

Somali-born former Dutch politician Ayaan Hirsi Ali recalls learning from her grandmother that “this hideous kintir, my clitoris, would one day grow so long that it would swing sideways between my legs.”

Without honor and the assurance of virginity/fidelity, and with the clitoris intact, it is assumed that a girl’s libido will become uncontrollable and she will be promiscuous, “dirty,” her genitals even possessed by the devil, who must be cut out. No one will marry her and she will bring shame on her family, become an outcast in her community. Both Hirsi Ali and Somali supermodel and UN spokeswoman Waris Dirie remember being labeled “disgusting” and “impure” at only 5 years old because they were not yet circumcised.

Other beliefs include the enhancement of fertility and the husband’s sexual pleasure. In some cultures the clitoris is seen as causing disease, even death, if the baby’s head or husband’s penis should touch it.

When religion and tradition become the same thing, some mistakenly see it as a religious

requirement, and it is even promoted by some religious leaders. In Bandung, Indonesia, where 100 percent of women undergo FGM, “mass circumcision” events are free of charge, sponsored by the Assalaam Foundation, a Muslim educational and social-services organization, believing that if a girl prays with unclean genitals, her prayers will not be heard.

These beliefs would not have sounded too far-fetched in the US or UK a century ago, however. Medicalized male and female circumcisions became seen as a “cure” for epilepsy, masturbation, and hysteria in the 1900s (thus the origins of the continued practice of male circumcision in the US today). L. E. Holt’s standard pediatric textbook Diseases of Infancy and Childhood, in publication 1897-1940, advised cauterizing the clitoris and blistering the vulva. In Sexuality and the Psychology of Love, Freud claimed, “The elimination of clitoral sexuality is a necessary precondition for the development of femininity.”

Long- and short-term medical consequences have been widely documented. Ironically, most highlight the fact that the purposes of FGM actually achieve quite the opposite:

• 10 percent of girls die as a direct result of the surgery (hemorrhage, shock, infection, and septicemia), and up to 25 percent die of later complications. Generally, no anesthetic or antiseptic are used. Dr. Comfort Momoh, a Nigerian-Ghanaian midwife, recounts: “Anybody with scissors and a blade can perform it. It could be a barber. In some markets in Nigeria quite openly there is a queue, and this is performed by a man removing the clitoris, and at the same time, using the same blade, performing some tribal marks on the chest. More than 90 percent of the circumcisers don’t have any anatomical knowledge and no medical training. They go in with the aim of removing it and sealing the area and they do more damage to the vulva area.”

- High ongoing infection rates and the formation of abscesses do nothing to improve hygiene, fertility, or the “attractive smell” of a wife.

- The use of shared instruments to perform the surgery can only further, rather than prevent, HIV transmission.

- Infibulated women, due to the vulva being sewn up, find urination can take around 15 minutes. The urethra has been covered, causing bladder stones and sometimes incontinence. When a hole the width of a matchstick has been left, menstrual flow can also back up, causing pelvic inflammation and infertility.

- Long-term pain from nerve damage, and pain during sex (for infibulated women, the husband must force his way through the scar tissue seal in order to penetrate her). This has been documented as reducing the husband’s sexual pleasure, rather than increasing it.

- Scar tissue cannot dilate during childbirth, so prolonged labor, excessive bleeding, tearing, and obstetric fistula are prevalent: The WHO estimates that maternal mortality doubles and infant mortality quadruples as a result of infibulation.

- Trauma occurs when girls are held down, often by their mother or grandmother, while the procedure is carried out. Most will not have known beforehand what is about to happen, and to be held down by a trusted adult deeply damages the mother/child bond. Dirie recounts that, as she lay in pain for weeks with high fever and infection,“All I knew was that I had been butchered with my mother’s permission, and I couldn’t understand why.” Post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and depression have all been observed as a result of the above complications which follow women throughout their lives.

With so many dangers inherent in the practice, why does FGM not stop? The reasons are as deep-seated as the original objectives. Gerry Mackie, professor of political science at the University of California at San Diego, points out that it can be equated to straightening children’s teeth: If an outsider were to tell us that it was bad for children, we would not believe them. If they proved that it caused long-term problems, we would still not want to be the only parents whose children had crooked teeth. If all the girls in a society undergo FGM, there is no basis for comparison with those who have not, and when it is a taboo subject there is no forum for discussion. Mackie also mentions “belief traps” and “self-enforcing beliefs: a belief that cannot be revised because the believed costs of testing the belief are too high.”

Where medical knowledge is extremely limited, the connection between FGM and complications may not be made: Are these problems not simply part of every woman’s life? Even when understanding is present, the benefits are seen to far outweigh the risks. If this is necessary for becoming an adult and being accepted in society, why would anyone risk ostracism (which, when resources are scarce, could also affect survival)? Coupled with the belief that female genitals are evil or shameful, and the bullying associated with not having undergone FGM, this leads some girls to actually request the surgery. The exact nature of this “informed consent” thus becomes a moot point.

Most of those who continue the tradition are women: mothers and grandmothers. This is because these women know very well how difficult a daughter’s life will be if she is unable to marry. As Dr. Momoh explains, it’s a question of providing as much security for your daughter as you can. “[FGM] is like insurance to them: Whereas in the Western community we want to educate our children, we want them to go to university, in some of the villages they are not educated, they don’t have means of education and so to secure a future for your daughter would be to FGM her. As a mother you want to do the best for your daughter, so they continue with FGM.”

In a culture where girls/women are dependent on their parents, then their husband, they have no choice over their own bodies (or, later, those of their daughters). Unmarried girls risk becoming a burden to their parents. For parents, ensuring a daughter’s virginity and therefore marriage ensures that she will no longer be an expense. Frances Althaus, executive editor of Inter-national Family Planning Perspectives, quotes Rogaia Abusharaf, “To get married and have children, which on the surface fulfills gender expectations and the reproductive potential of females, is, in reality, a survival strategy in a society plagued with poverty, disease, and illiteracy…. The socioeconomic dependency of women on men affects their response to female circumcision.”

She also quotes Nahid Toubia: “This one violation of women’s rights cannot [be abolished] without placing it firmly within the context of efforts to address the social and economic injustice women face the world over.”

The socioeconomic factor is also why circumcisers themselves will not easily give up the practice: It is their livelihood, and in a close-knit community they have every reason to know who has not yet been operated on and to make sure she soon is.

In recent decades, the practice has continued, or even increased, as a reaction against external intervention and perceived cultural imperialism. It is seen to preserve cultural identity and has been associated with nationalist and anti-modernization movements, which is perhaps why FGM is on the rise amongst immigrants to the US.

This perceived attack on culture is at the heart of some of the international controversies. Opponents of FGM have been accused of seeing African women purely as oppressed victims of culture, not as social agents in their own right. Practicing cultures point out Western double standards, observing our high abortion rates—even more harmful to children—and unnecessary cosmetic surgery. Increasingly popular “vaginal reconstruction,” “labia trimming,” and “hymen recreation” surgeries certainly involve “partial or total removal of the external genitalia or other injuries to the female genital organs for cultural or non-therapeutic reasons.”

Arguing the right to cultural expression is entirely valid, but feminists have pointed out that “culture” is not a monolith but constantly in flux, and while women do benefit from cultural rights, they suffer simply because they are women. Cultural rights and relativism do not address intra-group suffering and perhaps protect the perpetrators of FGM more than those at risk. Writers such as Nanci Hogan have suggested focusing on an ethic of human thriving rather than trying to universalize human rights or cultural rights.

Numerous pieces of legislation have been enacted that prohibit the practice (as I write, the Ugandan Parliament has unanimously voted in favor of illegalization). For those to whom FGM is an essential part of life, this is an encroachment by Westernism. For many years the UN hesitated to prohibit FGM outright, yet recent international, regional, and national laws that support the right to cultural expression are outlawing the defense of custom or tradition to perpetrate violence against women. FGM is condemned as a violation of human rights: the right to freedom from torture or cruel treatment; the right to life when FGM results in death; the right to the highest attainable health, bodily integrity, gender equality, and child rights.

Western nations have taken strong action against FGM: The US passed the Federal Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation Act in 1995, and the case of Togolese teenager Fauziya Kassindja set a precedent in US law in 1996, allowing women to seek asylum on the basis of the risk of FGM if they went home.

Legislation can only do so much to change attitudes, however, and it is increasingly being backed up by initiatives in many nations: In November 2009 Burkinabe First Lady Chantal Compaore called for a “zero tolerance” ban on FGM in Africa and asked all Africa’s first ladies to join her.

At a community level, education programs led by organizations like Tostan have been highly successful, challenging attitudes, raising awareness, and encouraging religious leaders to speak out against the practice. They provide practitioners with alternative means of income, persuade governments to include this taboo subject in school curricula, and teach men what really happens to their daughters due to FGM. Some communities have adopted alternative initiation ceremonies: In Kenya and Senegal, “circumcision by word of mouth” is gaining popularity, replacing traditional rites with a program of holistic education and coming-of-age ceremonies that celebrate the girls.

Among medical practitioners fighting FGM is Dr. Comfort Momoh, who advises women both at risk of and living with FGM and performs two to three infibulation reversal surgeries per week in London, UK. She advises healthcare workers worldwide, speaking on behalf of the World Health Organization and as an expert witness to the UK Parliament.

She stresses the importance of engaging with communities, rather than simply labeling traditions as “wrong.” In 2008 Queen Elizabeth II presented her with an MBE (Member of the British Empire) award for outstanding service to the Commonwealth. In Western nations, social workers, teachers, and police are slowly learning the warning signs when a girl is at risk of FGM. The French surgeon Pierre Foldès has perfected an operation that reverses FGM, which he performs free of charge to any woman who requests it. Despite death threats from Muslim extremists, he continues to operate, explaining, “Excision is worse than rape because the family are involved.”

In the arts, outspoken Senegalese rap artist Sister Fa held a tour last year titled Education sans Mutilation (Education without Mutilation), and speaks openly against what she underwent as a child. Former Somali supermodel Waris Dirie now serves as UN special ambassador for the elimination of FGM, using her status to speak on behalf of women world- wide. The movie of her autobiography, Desert Flower, was released at the 2009 Venice Film Festival.

FGM is a practice which often elicits moral outrage. But in reality we are all affected by harmful traditions in our own cultures: The pressures for girls (and boys) to look, dress, and act in certain ways are doubtless detrimental and are horrifying to most African cultures. We consent, or simply turn a blind eye, to many “normal” practices: What do we do to please the opposite sex, to be accepted, to get ahead? It is important to question our own reliance on cultural explanations of social practices: What core beliefs do we have which are less than God’s standard?

FGM is not in line with a gospel of health, healing, wholeness, and liberty. But in exposing abuses within a culture, we must not discard or denigrate the culture altogether. FGM can be stopped, but success is only possible through holistic engagement with our fellow human beings.

Olivia Jackson is a writer and filmmaker focusing internationally on advocacy with at-risk women and children. Her interests lie in raising awareness amongst the general public and strengthening political will to impact and implement policy affecting vulnerable women and children. She has made several films on social justice issues, often employing personal narratives and story to influence policy-makers and laws. Based in London, Jackson has lived and worked in Switzerland, the US, South Africa, and India. She wishes to extend her thanks to Dr. Comfort Momoh, Nanci Hogan, and Wendy Davidson for their kind assistance with this article.

womwom