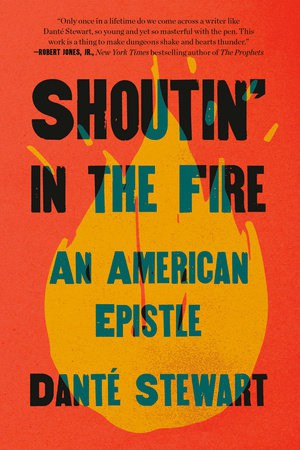

This month, we are introducing you to some incredible Black authors and thinkers who are helping us find a pathway to sustainable peace-building, ongoing reconciliation, and honest reflection. Today we talk with Danté Stewart, a speaker and a writer whose work in the areas of race, religion, and politics has been featured on CNN and in The Washington Post, Christianity Today, Sojourners, The Witness: A Black Christian Collective, Comment, and elsewhere. He received his BA in sociology from Clemson University and is currently studying at the Candler School of Theology at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. His latest book, Shoutin’ in the Fire: An American Epistle, is published by Convergent Books, a division of Penguin Random House.

This month, we are introducing you to some incredible Black authors and thinkers who are helping us find a pathway to sustainable peace-building, ongoing reconciliation, and honest reflection. Today we talk with Danté Stewart, a speaker and a writer whose work in the areas of race, religion, and politics has been featured on CNN and in The Washington Post, Christianity Today, Sojourners, The Witness: A Black Christian Collective, Comment, and elsewhere. He received his BA in sociology from Clemson University and is currently studying at the Candler School of Theology at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. His latest book, Shoutin’ in the Fire: An American Epistle, is published by Convergent Books, a division of Penguin Random House.

What does a faith that loves Blackness look like?

What does a faith that loves Blackness look like?

For me, it looks like embracing ourselves, loving all that we are and have been, centering our experience as the starting point for thinking about the world, and living out the many ways we have shown up in the world.

Toni Morrison has this quote that I love, one that I return to again and again. As she was thinking about her work on the 1974 classic The Black Book, she writes that the process was “like growing up Black one more time.” Encountering the ways we as a people have a distinctiveness, a uniqueness, in the way we live in the world and create life made her realize that this work was “an unconventional history told from the point of view of everyday people.”

Loving Blackness is just that: learning from this story of the everyday, ordinary power of Black people and the ways we take what we have and we turn it Black. It is the willingness to embrace the fullness of our humanity and liberation. But it is also the willingness to be self-critical; after all, we are human. It resists the many ways people tell us that Blackness is bad or opposed to faith or something to be devalued, distanced from or destroyed.

It is about seeing Blackness as something to be desired, embraced, and explored. Though people do not believe it: our art and literature and culture is sacred text, the stuff of the divine. Our lives are sacred history, the stuff of meaning.

What were the one or two formative lessons you learned after being wounded by the church and the people you most trusted?

I learned that oftentimes we name spaces as ultimate, when in actuality those spaces may just be the context where we have been led to believe that in this moment. What I mean is that, in hindsight, I thought the White evangelical church I had given so much of my life to was the space that I would remain in for years and years. It wasn’t until I was close enough and grew into myself and started to identify with my people that I actually started to see the space and the people for who they really were.

This lesson, it seems to me, can only come through time and experience. I was led to believe that these were the people and traditions that loved me when, in reality, both only loved me insofar as I performed in ways that assimilated to and protected their power and way of life.

It wasn’t until I left that I realized this, and I have become very careful of believing that wherever I am is the “final” place I will always be. Speaking of wounds, that process is a very discouraging and disorienting process. To blindly give yourself to people whose way of life is built on your oppression and to be forced to deal with that is a deeply hurtful process. But I am also reminded of Alice Walker’s words: “saw / what I considered a scar / and redefined it as a world.”

That was the biggest lesson: redefinition. I had to do the hard work of redefining ourselves. Indeed, many Black stories I have come to resonate with and center in my own self-understanding are stories of redefinition. James Baldwin, who is central to my work, went through the process. Audre Lorde went through that process as well. Toni Cade Bambara, Amiri Baraka, James Cone, Katie Cannon, June Jordan. All of these and more experienced hurt, loss, confusion, and pain. Yet each found a way to, in the words of Morrison, translate sorrow into meaning. For me, that’s power. That’s a lesson to try and keep on living.

What do we all need to know about the sin and bias lurking inside of our own hearts? How do we become people who name the hidden things?

Audre Lorde, in her essay The Transformation of Silence into Language, speaks to this very question. Writing in the context and at the intersection of faith, feminism, and sexuality, she says that silence is often times about maintaining power and control. It is silence that leads to distrust. It is silence that conceals who we are as people; if I can’t hear you then I can’t see you.

And bias, especially the kind that erases another or renders them mute and invisible, is about refusing to see and embrace another. To this, Lorde says that “it is not difference that immobilizes us, but silence. And there are so many silences to be broken.” To think about the language of breaking silence means we deal with ourselves in honest self-critical ways.

We cannot overcome or break bias if we are dishonest with ourselves about how we name, see, and act within the world. We cannot overcome this if we do not reconstruct the world to be a place where all people are heard, inspired, and protected. I guess what I’m trying to get at is about learning to break the silences in our lives as an ongoing process of growth and maturity. For our sin and bias do not just lurk in our hearts; they lurk in our lives–our embodied experiences, our systems and institutions, our stories and artifacts.

And this means looking again at those things and asking the question: Who is missing? Who is not seen or heard? Whose story is left out? For me, personally, that means listening to Black women and Black LGBTQ voices, and not just listening to their voices, but breaking the silences in my own life through friendship, compassion, following, and changing.

You talk about rage, resilience, and remembrance being spiritual issues. Why do we all need to press into these three if we are to reach true racial equality and equity?

For starters, I don’t think we can reach “true” racial equality in our lifetime and moment. Pessimistic? Yes, indeed. For history has given us no evidence to believe in such an audacious claim.

But history, our Black story, does suggest that life, Black life, is more than trying to reach a point where others will accept us and more about living in ways that we accept ourselves even as we push back against this anti-Black world. So to think about rage, resilience, and remembrance is not about reaching some point or destination that is often determined by people who keep us out of rooms, who exploit our vulnerability and creativity, and who construct the world in ways that protect their power.

It is about keeping tapped into our own humanity and power. Too often, Black life has been looked upon as something to teach others about “equality” or “justice” or “love” or whatever other term people use to see us and relate to us as mere products and transactions. That is far too limiting. Our lives are just about that: our lives.

So rage, resilience, and remembrance is not “for” other people. It is for us. It is how I stay tapped into the stories I come from and the stories that give me meaning. It is about feeling the full range of human emotion and not cutting myself off from parts of myself that could be keys to life. It is about living in and loving my Black life so much that I see every aspect as a tool or a way or a mode of living and moving and having my being. It is about the Black world–the world that we created and have made for ourselves. And if that world makes the larger world more just and equal, so be it. But that is not so much my concern as is about how we relate to our own selves and what we have built.

What advice can you give to those who feel marginalized in their church settings?

The advice I would give that person is threefold, though the advice will always go beyond that because that is life.

First, I would say: Don’t stay in a place that does not see you or embrace the fullness of who you are. Jesus wants us to be unified and in community but he does not want such unity to be built on another’s oppression or being made invisible. I stayed for a while in such settings. This never ends well. My presence was oftentimes what gave them power. And the more I stayed, the more angry and bitter I became. Anger and bitterness are not bad. I don’t want to think about them in the realm of morality but in the realm of emotional health.

When I remain, I’m going to be constantly reminded, and in forceful ways, of what others think of me and how they relate to me. That is very traumatizing. When you can find an alternative space or people, then we will have distance enough to heal from those wounds and live in ways that take back the power of our humanity. That is about healing and living and not just trying to “prove” our worth to people who don’t desire to accept us.

Second, I would tell that person to find ways to center those who look like them, learn that story, and use it as a way to redefine yourself. Marginalization is wrapped up in devaluing ourselves because we are told again and again that we are nobody. Redefinition is about self-love and self-respect. When June Jordan spoke at Howard University in 1978, she said, “I am a feminist, and what that means to me is much the same as the meaning of the fact that I am Black: it means that I must undertake to love myself and to respect myself as though my very life depends upon self-love and self-respect.”

That’s what centering is about: taking back the meaning.

Last, I would say: Be patient and forgive yourself. Regret is real. Self-blaming is real. And when we are in spaces that marginalize us, we often are negotiating ourselves in that space, and sometimes not in good ways. Being patient and forgiving means realizing that at one point that is who you were and where you were but now you have changed, are different, and have learned better.

That person is still you but now, this person is a different you. It is okay to cringe when you look back then, but also embrace the truth of who you are right now: and you should be proud of yourself. Change is not easy, but in the words of Octavia Butler, “ALIVE! Still alive. Alive…..again.”