In London, England, there is an attraction called the Churchill War Rooms, a museum dedicated to showing viewers the tunnels where Winston Churchill worked during the course of World War II. Not only are these tunnels recreated to showcase what life was like living in such cramped quarters, but the war rooms are also a museum covering the life of Churchill himself. Ever wanted to learn about what a “romper suit” is, or how Churchill once escaped a South African prison camp, or what political path he took after World War II? This is the place for you.

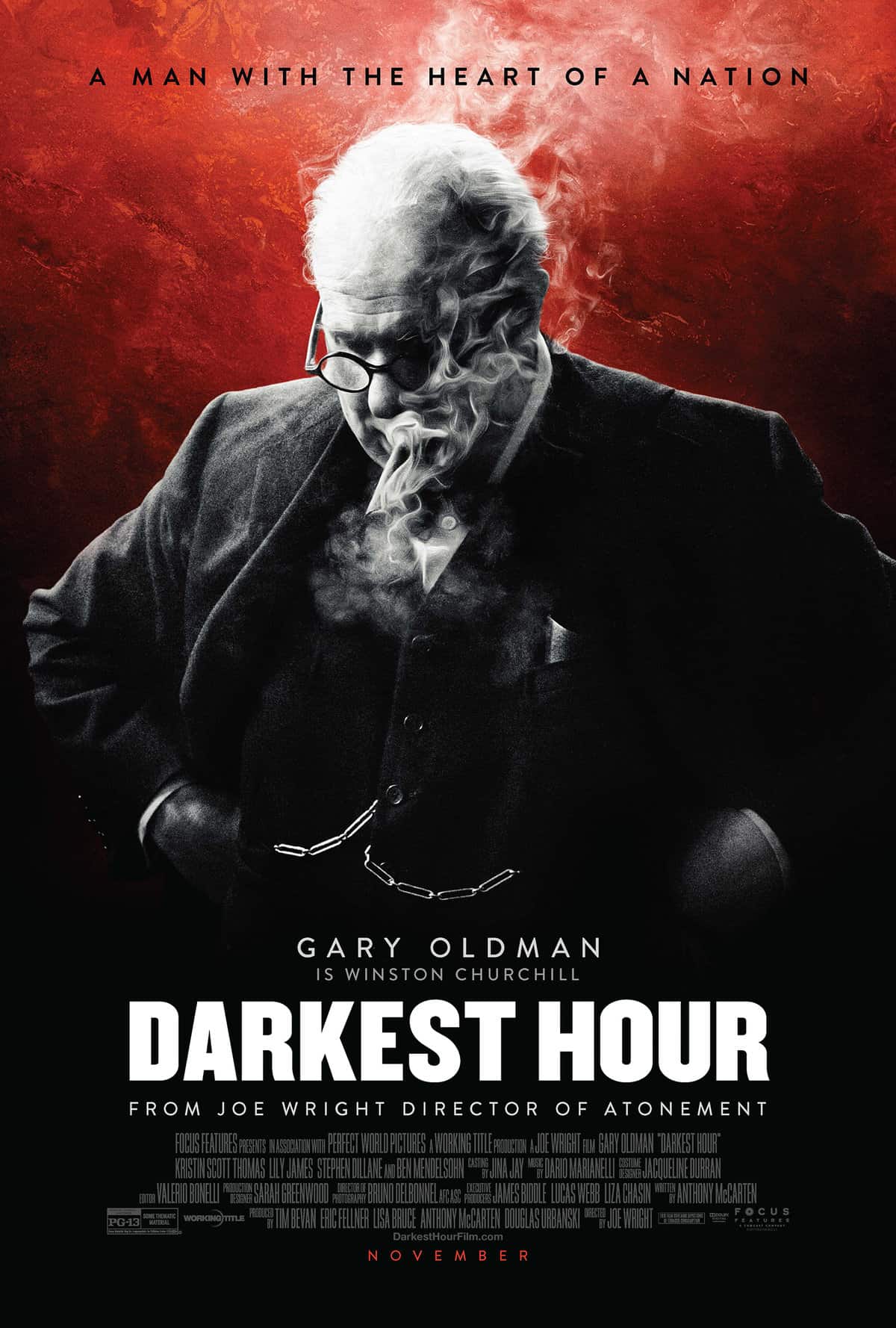

Joe Wright’s recent film Darkest Hour also allows viewers to get a glimpse of Churchill’s life, without having to visit England. It’s 1940, Hitler is beginning to conquer Europe, and a man as eccentric as Churchill (Gary Oldman)—who takes breakfast in bed, crafts a speech while bathing, and tells King George VI (Ben Mendelshon) that he cannot meet with him at 4:00 on Mondays because that’s when he takes his obligatory nap—seems the unlikeliest of people to be named Prime Minister of England during this bleak time. His opposition in Parliament, namely Lord Halifax (Stephen Dillane) and former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain (Ronald Pickup), certainly think so and try to do whatever they can to get him removed.

Oldman’s Churchill, however, is unwavering. Over the course of the film, audiences are treated to a prime minister who proves himself up to the task of directing England during the war. He strives to encourage France as they’re bombarded by Nazi forces; he pleads for much-needed assistance from President Roosevelt; he stands up to political opposition, showing his unflinching resolve against enemies outside England and within his own war cabinet. In such dismally dark days, Churchill is the one man even Hitler fears, the one man who will never back down even when his country is on the verge of war. Despite his eccentricities, Churchill is no dummy.

Churchill was a modern day Daniel, a man who found himself in the proverbial lions’ den of the German offensive.

And yet the film manages to portray a human side to Churchill as well. After his failed phone call to Roosevelt, the camera lingers on a much disappointed man. Interactions with his wife include rhetorical sparring, highlighting the witty side of their relationship. Heated discussions with political adversaries come with a bombardment of heartfelt words. Discussions with his new assistant, whom he berates at the beginning of the film, eventually become more friendly, even fatherly. The film makes it clear that this historical figure credited with helping England make it through the second world war was also a human, with very real emotions and relationships.

Nowhere is this clearer than in discussions regarding the rescue of Dunkirk, which becomes a major point of contention during the film, with Churchill staunch in his resolve that the men surrounded by German forces in that town must be rescued. Tensions come to a head between Churchill and Halifax in one scene where Churchill stands firm in his resolve that, in order to save the 300,000 British soldiers in Dunkirk, 4,000 men in neighboring city Calais will have to distract the German forces and thus sacrifice themselves. While Halifax argues the merits of a potential peace treaty (brokered by Benito Mussolini) between England and “Herr Hitler” to end further bloodshed, Churchill will have none of it. He is willing to make such a difficult decision, stating “A tiger cannot be reasoned with when your head is in its mouth.”

In some ways, Churchill was a modern day Daniel, a man who found himself in the proverbial lions’ den of the German offensive. And while Churchill doesn’t necessarily turn to God for a resolution (“My father was like God,” he says during the film, “busy elsewhere”) he knows how to shut the lions’ mouths.

Later on in the film, Churchill decides to board the underground subway system to interact with the people there. Away from meetings and audiences with kings and diplomats, he meets Londoners, learns their names, get their opinions on how they feel about Hitler and British policies. Again, his humanity is on display. Like so many Biblical leaders—David, Paul, Peter, and especially Jesus—Churchill approaches people, talks to them, listens to them, and takes time to understand issues from their point of view. Ultimately, these interactions shape his own policies and confirm for him the necessity of facing down the German enemy, no matter the cost.

“We shall never surrender,” Churchill tells Parliament shortly before the end of the film. And, as history shows us, he didn’t, and neither did England.

Humankind thrives on stories of unexpected leaders, heroes who reshape their people or worlds despite difficult choices and hostility. Winston Churchill was an unlikely man who became prime minister of England and led his country through an agonizing war, even with his political foes breathing down his neck. Darkest Hour definitely shows us a moment of deep shadow—during both England’s history and Churchill’s life—but it ultimately tells us that personal heroism and leadership can get us out of that darkness and into long-lasting light.

Nathan Kiehn is a recent graduate of North Central College in Naperville, Illinois, and writes for the blog Keenlinks.