By Anna Baker

I consider myself to be a patriot. I am thankful for the rights that American citizenship brings to my everyday life, and I am thankful for those who have fought for me to be able to have those rights. Among other things, those rights mean I can support, or not support, whichever political candidate I choose. I can speak openly of my religious opinions, choose which religious leaders’ opinions I will respect, and which I will listen to with a large dose of skepticism. I can post all about those topics on social media and not be subjected to censorship or be fearful that I will be thrown in jail because I liked a post. I can go out in my community and be relatively certain that I will come home at night. I can write these words in the comfort of my home without fear that I will be hauled away. I am relatively free from persecution in this country.

But here’s where my American patriotism gets confusing and heartbreaking – I have all of those rights, but some of my neighbors don’t. They don’t have the right to be on their own land without being attacked by dogs. They don’t have the right to celebrate their relationships openly. They don’t even have the right to quietly take a knee at a sporting event without being threatened with death.

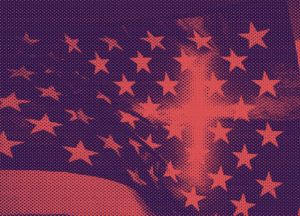

Perhaps even more heartbreaking, we have somehow conflated patriotism with our faith. We’ve so heavily enmeshed the two that we can’t seem to separate them anymore. We assign moral superiority to one candidate over another based on the endorsement of religious leaders, regardless of that candidate’s stance on issues or their personal ethics. Pastors endorse a political party from a pulpit and church members badger and belittle those who disagree. Friends have told me that I am abandoning the religious and moral training of my youth when I disagree with their choice of candidate or hot-button issue. Not only that, but they argue I must have a secret hatred for my country when I question the decisions of leaders and ask that we hold the powerful accountable for their actions. They tell me I need to repent, to pray and trust that God will show me his will, that if I would just submit to the guidance of godly leaders I would come back into fellowship with them once again and vote “correctly” so that America can continue to be the greatest country in the world. My patriotism (or perceived lack thereof) is seen as an extension or manifestation of my morality and personal faith.

Jason Foster describes this type of patriotism as “a frustrating faction of the faith. There are passionate but generic references to God, calls for fervent prayer and public pleas for ‘morality.’ But the alleged No. 1 devotion to God is usually tied to a No. 1 devotion to the Stars and Stripes, as if one must always be tied to the other.”

I see this type of patriotism every day. It’s the kind of patriotism that censors and judges. When I question the decisions of religious leaders to support a specific candidate, I’m told I must not be trusting God. When I agree that a person should be allowed to sit quietly during a national anthem if they so choose, I’m told I must hate my country and its armed forces. When I argue that a pastor should not be endorsing a candidate from the pulpit because that just flies in the face of “separation of church and state,” I’m told that not only must I be a heretic, but I’m unpatriotic to boot. When I say that the murder of people of color in this nation is unacceptable, I’m accused of hating the police.

But aren’t I well within my rights to say those things? How do these questions make me unpatriotic or unfaithful or hateful?

Here is an opportunity for patriotism to stop being confusing and frustrating and heartbreaking — patriots can say to their country, “I love you, but this is not acceptable. We can be better than this.”

Those rights I mentioned earlier? The ones that give me the freedom to support and say and be whatever I want? Those enable me to be a patriot. Those rights give me a platform to stand on and say that I will not allow injustice to continue unchecked or for us to give up on being and doing better. A platform that demands those same rights for all of my countrymen and countrywomen.

And this platform – well, it’s pretty big. There’s a lot of room for more of us.

Anna Baker is a graduate of the School of Leadership and Development at Eastern University and a former high school English teacher. Now a church administrator south of Atlanta, she spends her days finding meaningful ways for the Church to partner with the community around it and drinking too much coffee.