Why the Amber Guyger sentencing caused an uproar among people of faith

The oracle which Habakkuk the prophet saw. How long, Oh Lord will I call for help, and you will not hear? I cry out to you, Violence! Yet you do not save. Why do you make me see iniquity, and cause me to look on wickedness? Yes, destruction and violence are all before me, strife exists, and contention arises. Therefore, the law is ignored, and justice is never upheld. For the wicked surround the righteous; Therefore, justice comes out perverted.

~ Habakkuk 1:1-4

Many African American Christians had a wide array of responses to the periscope of the sentencing of Amber Guyger and the forgiveness shown by Botham Jean’s brother. Many felt that the act of forgiveness displayed to the murderer was a type of cheap grace, or what I call “cheap forgiveness.” American Christianity has molded African Americans to believe this forgiveness is the right thing to do, the Christ thing to do, especially when faced with white oppression.

I choose not to discuss the reaction of Botham Jean’s brother’s response, especially because I know the trauma of having a brother murdered, and the pain of having people infer how they think I should behave and the timeline in which I should act. I offer the family of Botham Jean nothing less than my deepest sympathy and the hope that they will find a great Christian therapist who is well-versed in trauma.

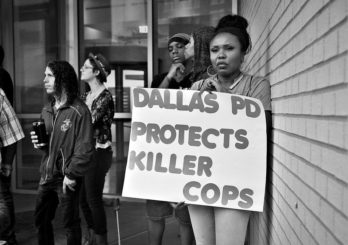

It seems everyone likes a happy ending. In this case, it seems to many that everyone got one. Forgiveness, sympathy from the judge, compassion from the bailiff, well-meaning Christians lifting the situation up as a model for how all true Christians should behave…and judging of those of us Christians who say, “Wait a minute, where is the justice?” There are those of us who believe that justice in this case has been perverted and the law has been ignored. Amid the many tears of compassion, you might forget the tragedy that brought us to this moment: another innocent, unarmed black man was killed at the hands of another white police officer. While jurors who never met Botham Jean were trying to sentence Guyger in the way that they thought that Botham would have wanted them to, they missed the crux of the matter, Botham Jean was no longer here because he was murdered and their job was not to try and locate his compassion, their job was to give justice to his murderer. I can’t help but wonder if Botham Jean’s innocent blood is still crying out for justice. I think it is.

Amid the many tears of compassion, you might forget the tragedy that brought us to this moment: another innocent, unarmed black man was killed at the hands of another white police officer.

As I watched Amber Guyger’s testimony I had a feeling in my gut that she was going to either be found not guilty, or she would get off with a light sentence. History has taught African Americans to view the justice system with a hermeneutic of suspicion. When Amber got on the stand and began to shed her “white girl tears” (a phrase coined by author Brittney Cooper in her book Eloquent Rage) I knew that justice would be perverted. I couldn’t help but think back to all the African American innocent men who were killed when a white girl cried. These tears of white women have been used against innocent African Americans, cunningly and convincingly, and many African Americans were lynched, brutalized and killed throughout the history of this country because of them. I bet Emmett Till’s accuser’s white girl tears were very convincing. She cried those same tears again on her death bed when she affirmed what many of us already suspected: Emmett Till was another black life stolen senselessly because of her lies and her tears.

Despite Guyger getting 10 years for murder (and she will probably end up doing only 4-5 of them), many of my Christian friends, pastors, etc. were elated by what they called “an act of redemption.” This quick and instant “forgiveness” was branded as Christlike and amazing. The black judge coming down off her bench to hug and cry with the convicted murderer, even giving Guyger her personal Bible. The black bailiff who compassionately stroked her hair. I must admit that the entire scene perplexed me. Then there was a backlash from many Christians towards any of us who were perplexed enough to ask questions that we thought were legitimate: Had this judge ever come off her bench to hug a black convicted murderer? What is going on?

I understand why my white social media friends were so happy. For them, it distracted us away from the important issues about race and policing that still must be dealt with. But my black Christian friends who were giving the side-eye to my comments and the comments of many others really had me confounded. Had anyone seen any of our black convicted murders humanized and shown so much compassion after being sentenced for murder? The sentence itself was perverted. An African American man who shot a police dog received 45 years for murder. A black man’s worth, even one of the “good ones,” was worth 10 years while a police dog’s life was worth 45?

Then people began to harp on how we should forgive. Forgive quickly. Some even spoke of radical forgiveness. I lament over those of us who have had our loved ones die because of senseless murder. Many well-meaning Christians were traumatizing us afresh and anew. In their self-righteous desire to have us say the words of forgiveness quickly and easily so we could put the situation to rest, they were surprised by some of us who responded “Hell no” to your quick forgiveness and your easy fix. Some of us have the courage to stand within the contradictions of perverted justice, systematic oppression, faith, restorative justice, oppressive social structures, and the brutal shooting of the main witness against Amber Guyger the day after her sentencing.

Some of us cannot or will not use that “forgiveness” word, because we don’t even know what that would look like amid the injustice of the murders of so many black men and women.

Some of us cannot or will not use that “forgiveness” word, because we don’t even know what that would look like amid the injustice of the murders of so many black men and women. We are asking our just God how to survive in the midst of the incongruity of a loving, peaceful God and a violent, unjust world. We are willing to lament to bring our grievances to God and wrestle with God until we are able to use the word “forgive” in a way that is justice-oriented and meaningful. Forgiveness for us is an act of God, and we are willing to endure the paradoxes of our faith until God grants us the ability to forgive.

Rev. Lori G. Baynard is the Director of Theology and Public Policy at Salvation and Social Justice; she is also the Director of Advocacy with Woman of Color in Ministry and is a United Nations Women. Lori is a wife, mother, daughter, and a sister who has had a brother murdered.

Rev. Lori G. Baynard is the Director of Theology and Public Policy at Salvation and Social Justice; she is also the Director of Advocacy with Woman of Color in Ministry and is a United Nations Women. Lori is a wife, mother, daughter, and a sister who has had a brother murdered.

One Response

Thank you, a beautiful perspective on this “perplexing” situation. I only hope these Christians will remember what they’ve said about forgiveness the next time an immigrant is accused of murdering a cute little 19-year-old white girl