We’ve been told that when the government separated my grand-uncle from his mother and sisters in 1941, he waited at a bus stop for his father to pick him up. What he seemed to have forgotten in his traumatized state, though, was that his father had passed away the prior year.

My grandmother cannot recount any feelings about this day when she was torn from her siblings. Whether she’s just lost her memory from old age—she’s now 93 years old—or she’s disassociated from that difficult period of her life, she remains reticent.

What she does recall is that she fought hard to keep her siblings with her. When my great-grandmother was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1941, my grandmother lied to the government and pretended that they had an adult relative living with her and her three siblings. For months they kept up this pretense and collected county welfare benefits until my grandmother also came down with tuberculosis.

“The day the social worker came was the worst day of my life,” my grand-uncle bitterly stated. The county worker indeed broke up the family, quarantining my grandmother in a hospital, and sending my two Chinese American grand-uncles, aged 13 and 8, to a Mexican American foster home. My grand-aunt, only ten at the time, was sent alone to a girls’ home. Because of segregation policies, Mexicans and Asians received poorer healthcare; they also could be deported for health reasons.

These experiences of my family connect to a larger trend. The United States government has a history of unjustly disrupting the lives of immigrant families through health and border policies. Just as ICE and detention centers along the United States-Mexico border are separating asylum-seeking families, the United States has long persecuted Chinese American ones.

Throughout the six generations that my family has been in the United States, we have always had to resist exclusionary, anti-family policies.

Throughout the six generations that my family has been in the United States, we have always had to resist exclusionary, anti-family policies. My great-great-great-grandparents migrated to Monterey, California in 1868 to elude the warfare and poverty that haunted them. Quite quickly, they faced a hostile United States government that worked to expunge Chinese immigrants. In 1875, the Page Act prevented Chinese women from migrating to California and hampered Chinese men from starting families here.

The year that my great-great-grandfather arrived in Monterey, anti-immigrant hysteria spurred the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. Despite opposition from missionaries working with the Chinese, Congress passed it overwhelmingly. My ancestors never could return to bury their deceased elders in China, a painful loss for them.

When faced with the renewal of the Exclusion Act in 1892, tens of thousands of Chinese engaged in mass civil disobedience and refused to carry the required alien cards. With the curtailment of immigration and family reunification, however, the Chinese population in the US quickly declined.

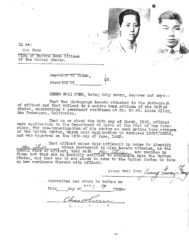

My great-grandparents also suffered from discriminatory border policies. Starting in 1910, the Angel Island Immigration Station detained Chinese before they could enter the U.S. Since all Chinese were suspected of skirting the Exclusion Act, both my great-grandfather and my great-grandmother underwent severe interrogation before being admitted. Much like the current prisons for asylum seekers, facilities at Angel Island were crowded and filthy, and several detainees allegedly died due to unsanitary conditions.

As before, the Chinese community again resisted to reunite with their families and protect dignity. My great-grandfather took on a “paper identity” so that he could enter and rejoin with his siblings. My great-grandmother probably agreed with her fellow detainees, who carved poetry into the walls to protest the poor conditions. Three times, Chinese rioted at Angel Island against their detention.

Fortunately, the Chinese community had allies in the Church at this time The Chinese YMCA frequented Angel Island to show movies and teach English. Deaconess Katherine Maurer, the “Angel of Angel Island,” helped to write letters and teach English, especially for children and their mothers. Similarly, Christian women supported my grandmother and her siblings when they were separated, and helped to reunite the family by driving them to be together on a regular basis.

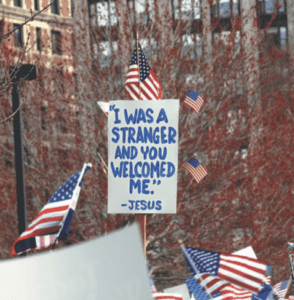

My ancestors, and the Christian benefactors who aided them, followed Biblical examples to cross borders and even engage in civil disobedience in order to preserve families.

My ancestors, and the Christian benefactors who aided them, followed Biblical examples to cross borders and even engage in civil disobedience in order to preserve families. At the risk of their own lives, the midwives Shiphrah and Puah refused to obey Pharaoh’s edict to kill Hebrew boys. In Jericho, Rahab disobeyed her king’s injunction and saved Israelite spies. From Moab, Ruth chose to remain a daughter to her mother-in-law Naomi, even by migrating to a new land. Boaz, following Levitical law, allowed the poor and foreigners to glean his fields and extended even more hospitality to Ruth. Jesus himself shared about the Good Samaritan, who risked defilement but nonetheless crossed ethnic lines to care for a Jew.

Justifying its actions through public health issues or labor concerns, the United States government has a long, xenophobic history of prohibiting, detaining, and tearing apart immigrant family life. The Chinese community, including my ancestors, rose up to protect their families and the broader community. May our examples, and those in the Bible, show us a better way and resist the current anti-family policies at the border.

Matthew Jeung is a sophomore at College Preparatory School and attends New Hope Covenant Church in Oakland.

Russell Jeung is Asian American Studies Professor at San Francisco State University. He is the author of a spiritual memoir, At Home in Exile: Finding Jesus Among My Ancestors and Refugee Neighbors (Zondervan 2016) which shares his family’s stories of migration and exile have taught him about faith and justice.