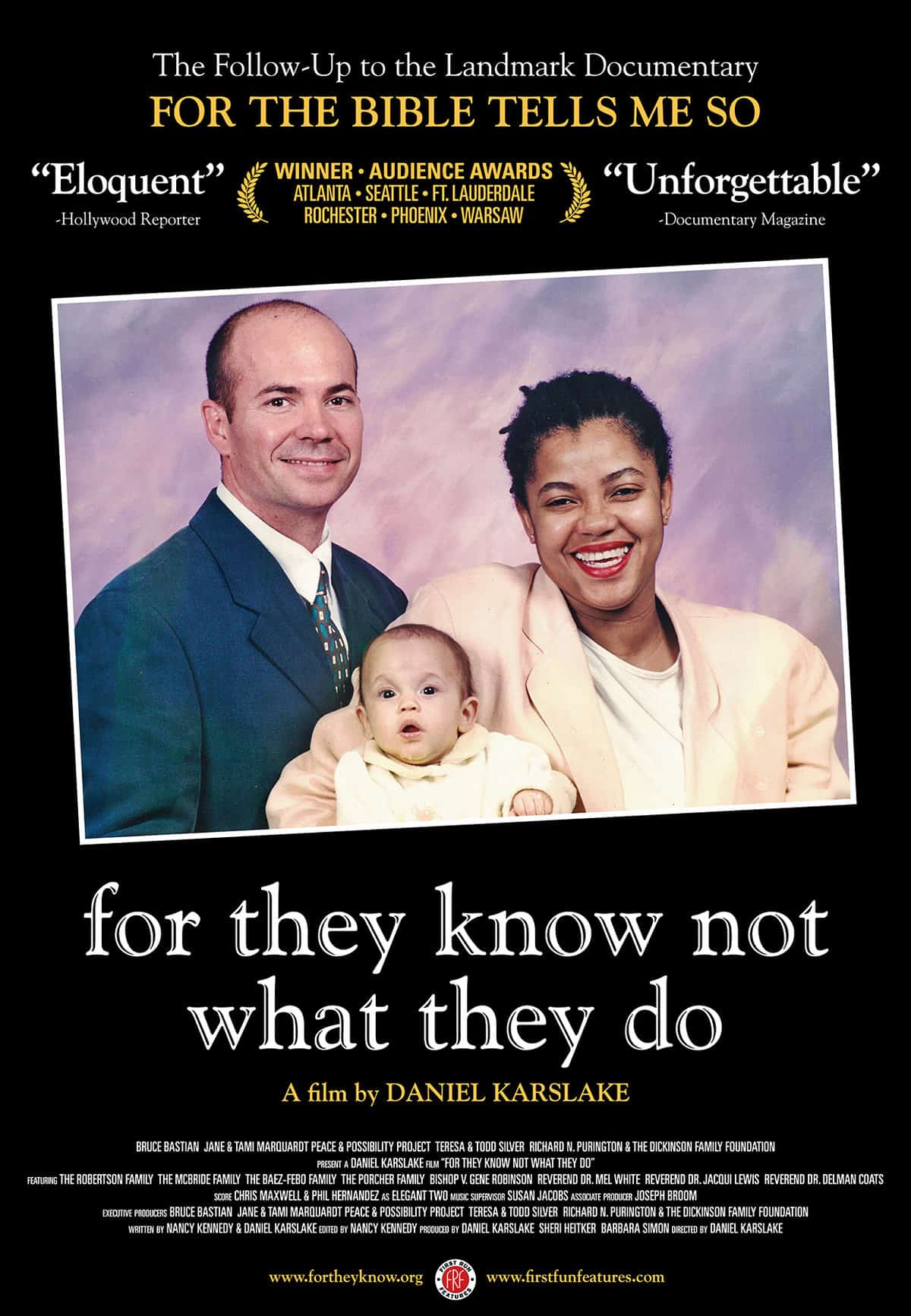

Daniel Karslake’s most recent documentary, For They Know Not What They Do, uses the power of personal stories paired with expert testimony to explore the real-world impact of anti-LGBTQ teaching. Highlighting the importance of listening to, believing, and walking alongside loved ones who identify as LGBTQ as they process what is almost always a difficult journey, the filmmaker calls us to take a clear-eyed look at the damage caused when Christians condemn LGBTQ people simply for experiencing their gender or sexuality in ways that are queer.

At times painful and heart-wrenching, Karslake’s film might be triggering for those actively processing religious trauma, but for friends and family of LGBTQ people, it’s a must-see.

The power of stories

The film centers on the lives of four LGBTQ people and their families, including Sarah McBride, who will be sworn in next month as the first transgender state senator in American history, and Vico Baez Febo, a survivor of the Pulse Nightclub shooting. Karslake focuses particularly on the struggle of parents learning to accept their children for who they are, and he structures the message in a way that many will find accessible, taking a compassionate view of friends and family members who hurt their queer loved ones, not out of malice, but rather because they “know not what they do.”

“Once Ryan came out, I felt like our lives were over,” confesses Linda Robertson, mom to Ryan, who disclosed his orientation to his parents as a young teenager. Ryan’s dad recalls telling his son, “This is a deal-breaker for God, and you cannot embrace a gay lifestyle without putting your soul in jeopardy.” In response, Ryan merely says, “I know.”

We follow Ryan and his parents down a predictable path of mental anguish and despair, during which Ryan at one point delivers an ex-gay testimony at an Exodus International event. It ends up taking a devastating toll. “Unintentionally we taught Ryan to hate himself and believe that he was completely unacceptable to God,” says Linda.

The consequences of ex-gay theology

What’s striking about Ryan’s story is that he followed all the “rules.” He went to conversion therapy, repented of all his sins, and begged God to make him straight. But no matter how hard he tried and how much he prayed, he couldn’t change his orientation. He believed himself condemned for something he couldn’t control.

Ryan’s experience is a tragic lesson in the consequences of a man-made theology that condemns people for no other reason than just because they’re gay. Whatever convictions people might have about sexual ethics—I myself follow traditional teaching—when gay people learn that they are inherently sinful for something they cannot change, it creates a theology of despair. The damage is often irreversible.

In Ryan’s case, he was young and incredibly impressionable and not even sexually active when he told his parents that he was gay. It didn’t matter. He might as well have confessed to the worst sin imaginable. Ryan’s parents observe that they were so worried about their son fulfilling all the negative stereotypes about homosexuality—sexually promiscuous, addicted to drugs, homeless, and anti-Christian—that their efforts to “cure” him ultimately drove him to the very extremes they feared. Not because he was gay but rather because ex-gay theology filled him with shame, self-loathing and despair.

Centering trans experiences

Karslake also centers the experiences of trans people and their loved ones, exploring the cost of rejecting a trans person’s identity, as well as the very real fear parents experience. “[Elliot] was cutting and wanting to die,” Elliot’s mother, Coleen, recalls, saying she worried she’d come home from work one day and find her child dead. The road Elliot’s parents travel to eventually accept Elliot, who was assigned female at birth, as their son is strewn with doubt. But they decide their doubts are not worth losing their child to suicide.

Sarah McBride’s parents experience a similar journey. Sarah’s mother describes her anxiety leading up to their first meeting with Sarah as their daughter instead of their son. She wonders whether she’ll be able to use female pronouns, if it will be awkward, or if she’ll be scared. But after a few short minutes of speaking with Sarah, she says, “I was completely comfortable.”

Both Sarah and Elliot’s experiences showcase the importance of respecting trans people’s gender identity and using the pronouns they use for themselves. It costs a cisgender person relatively little to use a trans person’s correct pronouns. But for a trans person, it’s often the difference between life and death, especially when it comes to being accepted by family and friends.

Solidarity amongst diverse stories

Debates in recent years have shifted from gay people as the primary bogeyman to trans people being the “thing” that conservative Christians fear the most—a crucial change that many gay rights organizations fail to acknowledge. Ultimately, the film creates a sense of solidarity between gay and trans people and their fight for acceptance, a solidarity that will be crucial in the coming years.

In addition, the film’s racial diversity was also noteworthy, featuring a trans man of color as well as a gay man of color. For me, as a Puerto Rican of mixed descent, Vico Baez Febo’s story felt particularly meaningful, as he walks viewers through his harrowing experience at the Pulse Nightclub.

“Till this day,” Vico says, “I don’t have a moment where I can think back at what happened and I don’t cry.” He shows a tattoo on his arm that he got in the massacre’s aftermath: “Hold on. Pain ends.”

People too easily forget that almost 50 percent of the victims in the Orlando shooting were Puerto Rican, and a full 90 percent were of Latin American descent. LGBTQ people of color face greater risk of discrimination, assault, and violence than do their white LGBTQ peers. It was refreshing to see this aspect of the LGBTQ experience highlighted in the film.

No strong theological case for LGBTQ affirmation

I deeply appreciated this documentary. It exposes the real-world impact of anti-LGBTQ teaching, and for me, its central theme rings true. Most people in my life “knew not what they did” when they made me believe that being gay was inherently sinful. A lot of times they genuinely believed they were doing God’s work. Most Christians still don’t know how high the stakes are, and I talk to people regularly who actually believe that harm towards LGBTQ people in the church is rare.

Friends and family who watch this documentary will also be able to see themselves and their feelings reflected on screen, which means they’ll be more likely to listen when they are challenged to consider the consequences of anti-LGBTQ teaching in the church.

At the same time, even though the documentary is emotionally compelling, it fails to present a strong theological defense for affirming LGBTQ people as children of God like everyone else. Many conservative Christians like to stereotype LGBTQ “rhetoric” as nothing but emotional manipulation, pulling on your heartstrings to make you feel bad but never considering God’s Word. This film runs the risk of confirming that stereotype for anyone who needs more than a collection of stories.

This is a real problem. Harslake could have easily addressed it by making better use of the experts, asking them to tackle common theological snags, and having them break down the biblical case for affirmation. Instead, the experts give an assortment of hot-takes and soundbites. They sound authoritative and add punctuation to the stories but ultimately fail to present any coherent case for LGBTQ affirmation from Scripture.

This is disappointing because there is, in fact, a coherent case for LGBTQ affirmation from Scripture. By failing to present that case well, the film may unintentionally reinforce the idea that affirming theology is nothing more than following “your heart.” For more theologically-minded viewers, the film’s impact may be blunted, making Christians kinder toward LGBTQ people but ultimately failing to change their perspective.

Final take

I highly recommend For They Know Not What They Do for family and friends of LGBTQ people. However, if you’re the type of person who needs more intellectual/theological engagement (or you watch this with someone who does), I’d pair it with a book. Kathy Baldock’s Walking the Bridgeless Canyon, for example, does a great job unpacking the ways in which homophobia became attached to Scripture and Christian doctrine.

For me as a queer woman, watching this documentary felt like watching my own journey. The shots of pastors condemning homosexuality hit hard and brought back memories of the many similar condemnations I’ve heard throughout my life. The more Christians hear stories from people like me and those in the film, the more things will change. In the end, For They Know Not What They Do makes an important contribution to building a church where everyone can flourish, including LGBTQ people.

Bridget Eileen Rivera is a writer, speaker, and educator completing her doctoral studies in sociology. She engages in public advocacy related to faith, gender, and sexuality, challenging the church to do better in its inclusion of LGBTQ people. Her first book, Heavy Burdens (Brazos Press, expected fall 2021), unpacks the legacy of LGBTQ discrimination in the church, helping Christians better understand the experiences of LGBTQ people within Christianity. Learn more about Bridget on her website, and be sure to check out her blog, Meditations of a Traveling Nun, where she writes about her faith journey as a celibate gay Christian. You can follow her on Twitter @travelingnun.

Bridget Eileen Rivera is a writer, speaker, and educator completing her doctoral studies in sociology. She engages in public advocacy related to faith, gender, and sexuality, challenging the church to do better in its inclusion of LGBTQ people. Her first book, Heavy Burdens (Brazos Press, expected fall 2021), unpacks the legacy of LGBTQ discrimination in the church, helping Christians better understand the experiences of LGBTQ people within Christianity. Learn more about Bridget on her website, and be sure to check out her blog, Meditations of a Traveling Nun, where she writes about her faith journey as a celibate gay Christian. You can follow her on Twitter @travelingnun.