A lesbian friend of mine shared the new Heineken “Worlds Apart” advertisement with me on Facebook, along with this comment: “WOW. Okay, Church, a beer company is responding like Christ would—what do we do with THAT? I don’t even like beer, but I say we take notes and GO AND DO LIKEWISE!!!!”

A lesbian friend of mine shared the new Heineken “Worlds Apart” advertisement with me on Facebook, along with this comment: “WOW. Okay, Church, a beer company is responding like Christ would—what do we do with THAT? I don’t even like beer, but I say we take notes and GO AND DO LIKEWISE!!!!”

For those who haven’t seen it, the ad depicts three pairs of people who meet for the first time, collaborate on a DIY project (piecing together a bar, becoming chummy along the way), share a few personal reflections with each other, and eventually discover that they disagree vehemently on a core issue (and that they also tend to vilify those who don’t see that issue their way). Once their beliefs are made known to each other, will they stomp away angrily, or will they sit and share a beer and agree to discuss their differences civilly? You can guess which choice they make. It’s a beer ad, after all (perhaps above all).

As a facilitator of dialogues across deep difference, I resonated with and enjoyed the ad. Although I’m aware of how easy it is to edit film to make a point (how many filmed pairs did end in angry stomp-offs?), I appreciated what they were demonstrating—that as easy as it is to demonize people we don’t know, once we’ve worked side by side with them, even for a brief time, we might be willing—when unsettling information is introduced—to drop our walls a bit and consider their shared humanity.

I’m highly suspicious of corporations foraying into justice messaging, because they are primarily at the service of their bottom line, and in their hands justice is just another sales tool. When you blur the lines between message and motive, you should expect folks to be a bit skeptical. For example, as much as I admire the message of Dove’s “Real Beauty” ad campaign, which assures women that their value lies in their individuality and not in their conformity to mainstream (read: impossible) beauty standards, their motive is clearly not love for women but the desire to sell Dove products. The fact that Dove’s parent company, Unilever, also owns the Axe brand for men, for which it long created ads depicting highly sexualized and commodified women’s bodies, makes it obvious that profit—not women’s mental health—is the driver here.

So I completely understand the desire to give the Heineken ad the side-eye, as some have. This writer has some very valid points, although I don’t find her tone particularly helpful—a tone I work to keep out of the Oriented to Love dialogues I facilitate. But despite the reservations, I’d like to take a look at what’s worthwhile in the ad.

1) The ad reveals how desperate we are for an alternative to disembodied ideological conflict—to the kind of over-the-top demonizing that is too often “business as usual” in both our personal and political arenas. What if we all agreed on—and rallied around—our desire for true conversation? True conversation, as Westboro Baptist Church refugee Megan Phelps-Roper sees it, involves not assuming ill intent of one’s opponent, asking questions, staying calm, and crafting a good case for one’s view. If Phelps-Roper can do it, after a lifelong indoctrination in hate speech and ideological terrorism, surely anyone can.

2) The ad demonstrates the essential goodness of working together. Participants are required to follow instructions and help each other reach a goal that is not immediately apparent, putting them on equally vulnerable, uncertain footing. In order to succeed, they must communicate, collaborate, and trust each other. They learn things about each other by observing how their partner responds to the directions, the physical challenges, and the need to cooperate.

Want to get to know and love your neighbors? Work side by side with them. Build something together; plant a garden; clean up a park. That is the premise behind the Interfaith Youth Corps, which helps young people connect toward a common goal and along the way discover that their religious differences are opportunities to delight in and learn from each other, rather than reasons for suspicion and division.

3) The ad highlights the incredible courage of people like the ones who apply for and take part in our Oriented to Love dialogues (OTL). Because unlike the people manipulated by Heineken, OTL dialoguers know from the outset that many of the 11 people with whom they will spend 48 hours in an intimate setting hold theological convictions very different from their own. They know they’ll be sharing a meeting space and long hours and many meals with people of sexual and gender identities unlike their own, people who in some cases come from denominations or institutions that have been the source of great pain for them.

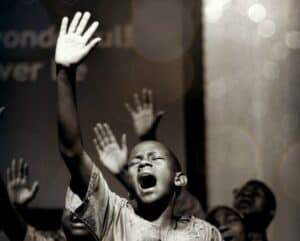

And they come not in spite of those deep differences, but because of those differences. They come nervous but hopeful, afraid but willing to risk being vulnerable, wary but open to being surprised. And what happens at these dialogues can never be captured in a four-minute ad or even in words on a page. Because it’s the work of the Holy Spirit, who like the wind moves things around in a powerful way but is invisible and mysterious. But the results are undeniable: OTL dialoguers leave the experience not just as friends but as deeply connected siblings in Christ—their minds often unchanged on doctrine, but their hearts always transformed towards those they once called “other” and now call sister or brother.

And I think that’s worth raising a glass (or a cold bottle of brew) to: Here’s to ideological conflict transformed into compassionate curiosity, to hearts converted to love.

Kristyn Komarnicki is the director of CSA’s Oriented to Love dialogue program.