A beautifully orchestrated dance that explores our internal struggles and joys as they bump up against our physical reality

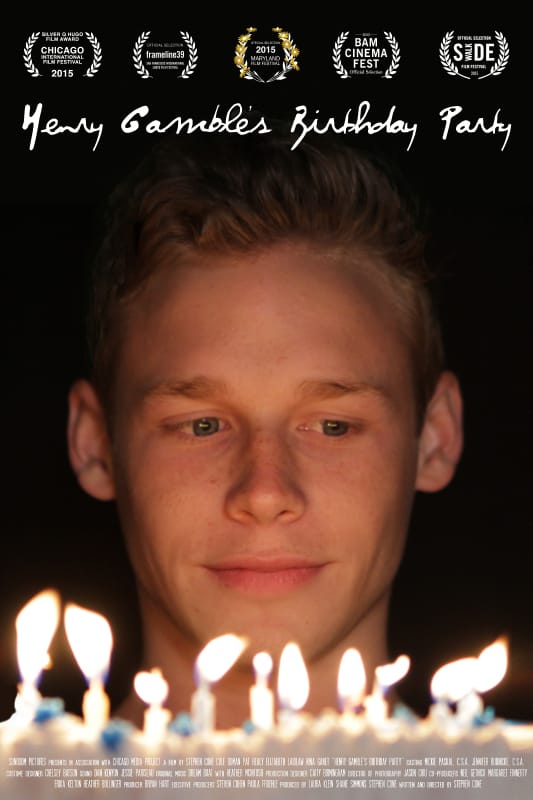

Set in in the microcosm of a pool party for the teenage son of a Midwestern megachurch pastor, Henry Gamble’s Birthday Party takes a macrocosmic look at the questions and concerns that confront many faith communities. Sexual orientation, infidelity, premarital sex, teetotalism, tribalism, self-righteousness, kindness, community, family, and love are all beautifully illustrated in this one-day portrait of intersecting lives.

Writer-director Stephen Cone (The Wise Kids, 2011) offers an appealing mix of insight and intrigue in his latest film. While the film is notable for its adept use of ensemble acting, beautiful subtext-driven cinematography, and well-curated synth-pop score, we will focus here on the spiritual impressions that Henry Gamble’s Birthday Party evokes.

Henry’s parents, Pastor Bob and Kat, spend the day navigating a number of tacit landmines. Their anxiety is palpable as love, fear, and resentment vie for the upper hand and as they struggle, with diminishing success, to keep face and present a reassuring façade for their guests as well as their children. Under Cone’s skillful direction, they convey the tremendous weight of all that remains unspoken as they dutifully fulfill their expected roles.

The rich cast of characters also includes Larry, the older but fun-loving associate pastor who, having observed the human drama played out at the party, at one point muses with compassionate sorrow, “So many stories.” Larry’s wife, Bonnie, on the other hand, is bound by a strict piousness that keeps her from being present to her own life; she is so disconnected from herself that she doesn’t notice the tears running down her face until another guest calls her attention to them. Bonnie occupies a lonely place of fear and judgment, having lost sight of God’s presence at work in the people and the world around her.

Appropriate to a story centered around an adolescent, the film pulses with an electric sexual undercurrent. Impressively, however, Cone never allows that undercurrent to become lurid or exploitive. It remains rooted in a deeper exploration, involving the characters’ need for intimacy, their desire to be desired, and the subsequent shame that weighs heavily on the hearts of many of the film’s characters. It is not the desires themselves that come across as negative and dangerous but rather the labeling of them as unnatural and shameful, which serves to alienate these friends and family members from each other and even from themselves. The shame causes them to withhold parts of themselves from those they love and makes it harder for them to be present for grace when it appears.

At the heart of the film is the suggestion that in our desire to be righteous—and for others to be the same—we can easily set ourselves up for a deadly cycle of self-absorption, judgment, and self-righteousness. In doing so, we fail to live up to the God’s highest call—to love with abandon, to be one with each other just as Christ and the Father are one. Focusing on behavior, whether our own or others’, we can easily miss the many opportunities we are given to experience joy and compassion, to offer and receive kindness and forgiveness.

At a certain point in the film, a breakthrough occurs, and Henry’s mother, sister, and Bonnie’s adult daughter Grace all get in the pool. For Grace, simply dipping her toe in the water is a huge triumph—a first baby step on what will be a long journey of needing to exorcise her mother’s demonized interpretation of the world around her.

The partiers enjoy the water, laugh, and delight in connecting with each other, but this is cut short as two young men from the church’s youth ministry, clearly uncomfortable with the earthy frivolity of the scene, take it upon themselves to lead everyone in a song of praise. Their good intentions are understood by the other characters, but the young men have nonetheless missed the mark; the moment of jubilant joy and gratitude for the gift of life is suddenly and irrevocably deflated. The unselfconscious praise that was expressed in their communal play has been replaced with an uncomfortable song of duty.

Meanwhile, Ricky, a socially awkward young man who is rumored to be “deviant” in his sexuality, is upstairs grappling with acute self-hatred, alienated from the group celebration both by their discomfort with him, which he experiences as covert rejection, and a jammed bathroom door that he is unable to force open. Henry himself is grappling with a similar issue, but he projects his shame onto the one person who is most likely to understand, a gay classmate named Logan who, as only one of two people of color in the group, is affected by a double whammy of marginalization within this Midwestern megachurch community.

Dedicated to endowing each of his characters with rich specificity, Cone has created a deeply human and complex depiction of Christ’s broken body as revealed in one church community. Cone’s respect and appreciation for people of faith, combined with his thoughtful direction, make Henry Gamble’s Birthday Party a poignant portrait of sin and grace, blundering and beauty.

Shannon Beeby is a writer, filmmaker, and co-founder of Bee Nest Films.