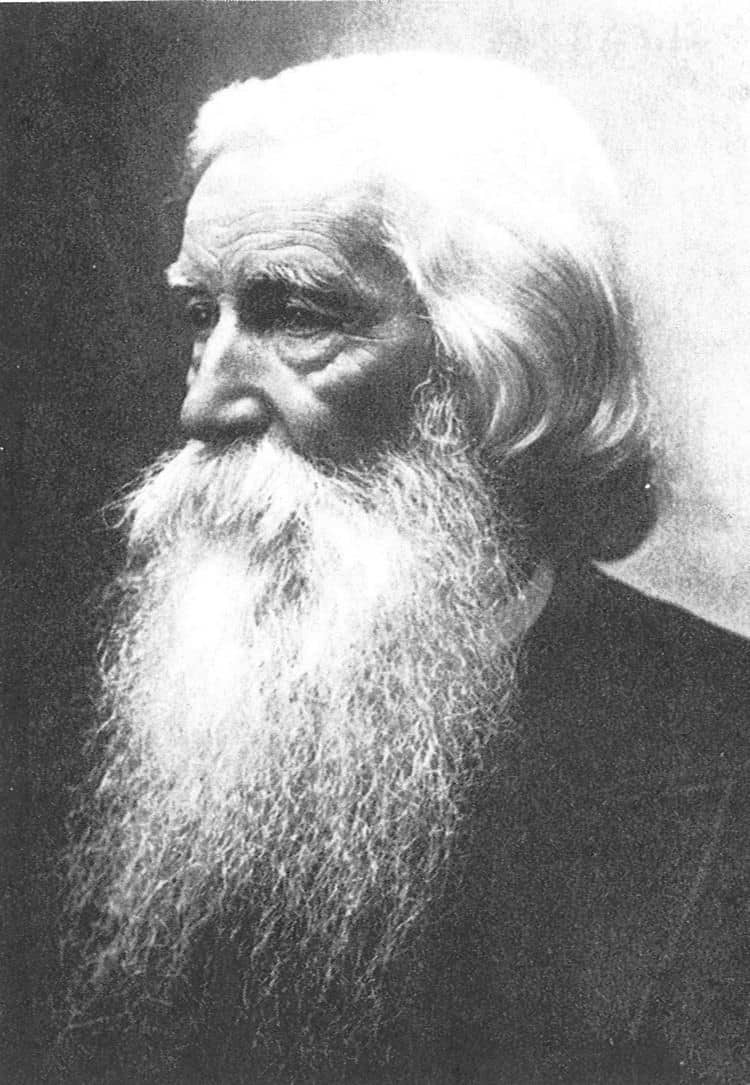

(1824-1907)

(1824-1907)

Spear-carrying cannibals setting his house afire, an irate chief stalking him for hours with a loaded musket, a native suddenly rising up from a sickbed and holding him captive with a dagger to his heart—the life of John Paton reads at times like a lurid adventure story, with the hero saved at the last possible moment by his own death-defying heroics. But it was not derring-do that carried the Scotsman through—rather a steadfast faith in God and a total willingness at each cliffhanging juncture to either meet his Maker or pick up his Bible and plow forward with his work among the tribes of the New Hebrides.

John Gibson Paton was born in 1824 near Dumfries, Scotland, to a humble, God-fearing family of the Reformed Presbyterian tradition. As the eldest of 11 children, he was forced to leave school at age 12 to work alongside his father in the family trade of stocking-making, but he pursued serious religious studies whenever time and money permitted.

Seeking a wider influence than his small village could offer, young Paton obtained a position as district visitor and tract distributor for a church in Glasgow, with the privilege of attending the Free Church Normal Seminary. In addition to his divinity studies, he studied medicine at Andersonian Medical University.

In 1847 Paton began an enormously fruitful ministry as a city missionary in one of Glasgow’s poorest districts. He brought hundreds of unchurched people to his Bible classes and services, and his admirers were shocked when he announced after 10 years that he intended to leave Glasgow and volunteer for the mission field in the New Hebrides. It was a hazardous field: The first missionaries to this South Seas island chain, sent by the London Missionary Society, had been killed by cannibals immediately after going ashore in 1839, and the next team (1842) had been driven off after seven months. Missionaries sent from Nova Scotia in 1848 and Scotland in 1852 fared far better, with about 3,500 people on the island of Aneityum renouncing their idols and accepting Christ, but assignment to the New Hebrides was still perilous when Paton made his decision.

Events moved swiftly. Paton was ordained as a missionary in March of 1857, married Mary Ann Robson a week later, and set sail for the South Seas with his bride two weeks after the wedding. After a brief landing on Aneityum, the young couple was sent to Tanna to establish a new mission station. The Patons found themselves surrounded by “naked and painted wild men” who had no regard for human life and no sense of ordinary human kindness or orderly conduct. A few months after their arrival, Mrs. Paton gave birth to a son, but she suffered immediate attacks of ague, fever, pneumonia, and delirium and died three weeks later. Two weeks after her death, the little boy succumbed to the same sickness, and John Paton dug a second grave beside the little house he had built upon their arrival.

Paton toiled on alone for the next four years, coming back to the graves of his wife and son whenever he needed comfort. “That spot became my sacred and much-frequented shrine,” he wrote in his autobiography, “during all the following months and years when I labored on for the salvation of the savage Islanders amidst difficulties, dangers, and deaths … But for Jesus, and the fellowship he vouchsafed to me there, I must have gone mad and died beside the lonely grave!”

During these early missionary years, Paton suffered repeated bouts of the same fever and ague that took his family from him, but the main danger to his life came from the very natives he was trying to convert. Over and over he was attacked by angry tribesmen with spears, axes, and muskets, but each time his life was spared. “Looking up in unceasing prayer to our dear Lord Jesus,” he wrote, “I left all in his hands till my work was done. Trials and hairbreadth escapes strengthened my faith, and seemed only to nerve me for more to follow; and they did tread swiftly upon each other’s heels.”

Even though Paton won the confidence of several warrior chiefs during these years and made many conversions, the superstitious natives blamed the “white devils” for an epidemic that swept the islands in 1861 and all his progress seemed to come undone. A Canadian missionary and his wife were slaughtered on neighboring Erromango, and the emboldened Tannese intensified their attacks on Paton. After several narrow escapes, including a miraculous deliverance from fire, he was finally rescued by ship, taking with him only his Bible and some translations he had made into the native language.

Cannibalism, widow sacrifice, infanticide, ancestor and idol worship: “Their whole worship was one of slavish fear. And so far as ever I could learn, they had no idea of a God of mercy or grace.”

After a brief respite at Aneityum, Paton sailed to Australia and immediately began making fervent pleas on behalf of missions to the New Hebrides. His eloquence and rather startling experience gained him a rapt audience and much-needed financial support. From there he went back to Scotland to recruit missionaries for each of the islands and to raise money for the construction of a sailing vessel to help them in their evangelical work.

Arriving back in the New Hebrides in August, 1866, Paton brought with him a new wife, Margaret (“Maggie”) Whitecross Paton. Together they established a mission station on Aniwa, the nearest island to Tanna, living in a native hut until they built a home for themselves as well as two houses for orphan children. On Aniwa they found the natives to be very similar to those on Tanna—practicing cannibalism, widow sacrifice, infanticide, and ancestor and idol worship. Chiefs were deified and had great influence for evil. “Their whole worship was one of slavish fear,” Paton wrote. “And so far as ever I could learn, they had no idea of a God of mercy or grace.”

Introducing Christian ideas into such an atmosphere often seemed impossible, but the couple pressed on. Paton learned the Aniwa language and reduced it to written form, then trained native teachers and sent them to outlying villages to preach the Word of God. His wife organized classes of women and girls and taught them Christian hymns as well as how to read and sew. Together the couple ministered to the sick and dying, held worship services, and instructed the natives in the use of tools. Tribal members continued to launch plots against the missionaries, but the Patons lived to see the entire population won for Christ.

Six of the Patons’ 10 children were born on Aniwa, but sadly four of them died in infancy or early childhood. The missionary couple stayed on the island until 1881 and then began making frequent pilgrimages to Australia, Great Britain, Canada, and the United States to promote interest in New Hebrides missions. Paton was an incredibly successful fundraiser, particularly after his autobiography was published in 1889, but he always insisted on frugal use of the moneys raised. Paton also wielded his influence to get British and American authorities to crack down on local traffic in firearms and alcohol and was vociferous in fighting a proposed annexation of the islands by the French.

In 1899 he saw his Aniwa translation of the New Testament printed and the establishment of missionaries on 25 of the 30 islands of the New Hebrides. Attending the Ecumenical Missions Conference in New York City in 1900, he was hailed as a great missionary hero. Mrs. Paton died in Melbourne in 1905. Although quite frail by now, John Gibson Paton continued to preach the cause of missions in churches across Australia until his death in 1907.

~ Leslie Hammond