(1552-1610)

(1552-1610)

Conversion of the Chinese people to Christianity seemed a fruitless cause in the late 16th century. The early influence of Nestorian missionaries in the 7th century and Catholic monks in the 13th and 14th centuries had withered completely, and recent missionary efforts by various Catholic orders had been stonewalled by Chinese authorities.

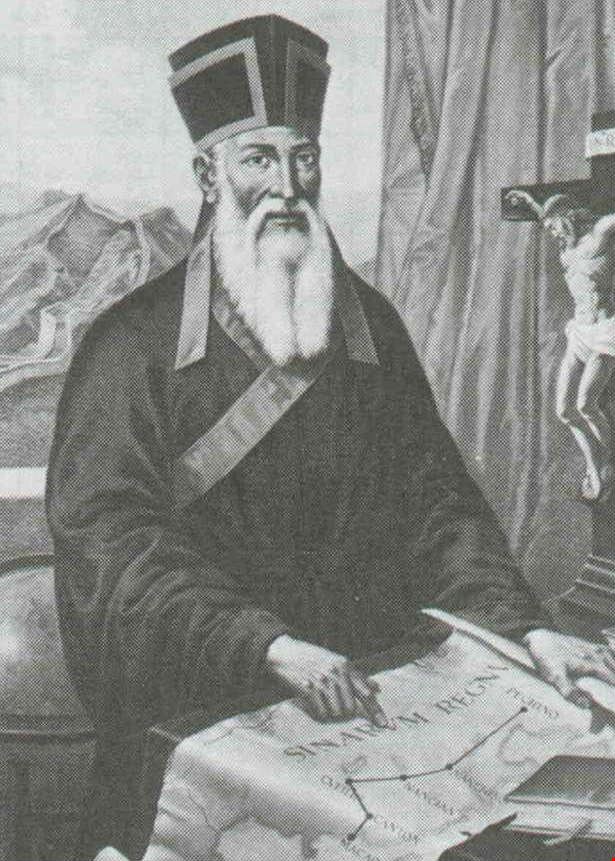

Into this atmosphere came an Italian Jesuit priest, Matteo Ricci, who confounded his coreligionists by taking a different tack in bringing Christianity to China. Rather than taking the attitude that he was bringing enlightenment to an ignorant people, he armed himself with knowledge about the culture he was entering and demonstrated respect for the profound intellectual curiosity he encountered. He also demonstrated infinite patience and tact, knowing that the message he was carrying was worth the wait.

Ricci was born in 1552 in Macerata, Papal States. Discussion of religion was prohibited in his home, but the young boy was increasingly drawn to the theological teachings at the local Jesuit school he attended. At the age of 17 he went off to Rome to study law but soon yielded to the call of the priesthood, entering the Society of Jesus at the College of Rome in 1571. In addition to studying philosophy and theology, he also studied mathematics, cosmology, and astronomy under the celebrated Christopher Clavius, studies that would later serve him well in China.

In 1577 Ricci announced his desire to become a missionary to the Far East, and the following year he was dispatched by the Jesuits to the Portuguese Indies, where he spent the next four years in ministry and teaching. Finally he received the summons to come to Macao and prepare to enter China. There he waited for five years, enduring obstacle after obstacle, until the authorities finally admitted him and a fellow Jesuit, Father Michele de Ruggieri, to take up residence at Chao-k’ing, the administrative capital of Canton, in 1583.

While waiting in Macao, the Jesuit fathers had applied themselves to learning the Mandarin language and had also learned something of the Chinese mindset. While they did not hide their faith or the fact that they were priests, they knew they had to overcome Chinese pride and fear of foreign influence before they could take the initiative in sharing their Christian message. Their first step was to display in their house a picture of the Virgin Mary with the infant Jesus in her arms. Chinese visitors always inquired about the meaning of this picture, and this gave them an opportunity to share the basic tenets of Christianity.

Realizing that the Chinese had a natural intellectual curiosity, they also displayed other things they had brought with them—clocks, mathematical and astronomical instruments, books, paintings, maps, and architectural drawings. Word soon spread of the marvels the European priests had in their home, and the object that drew the most interest was a beautifully drawn map of the world. The Chinese had maps, too, but they showed the world beyond China as consisting only of a few islands totaling a size less than the smallest of the Chinese provinces. Although Chinese scholars at first protested the validity of the European map, they eventually accepted that it had been carefully constructed by learned geographers and asked Father Ricci if he could draw a replica with the names of the countries, rivers, and oceans in Chinese. When it was completed, the governor of Chao-k’ing had it printed and gave copies as presents to his influential friends.

Father Ricci wrote in his journal of the importance of this map to his missionary efforts: “This was the most useful work that could be done at that time to dispose China to give credence to the things of our holy Faith. . . . Their conception of the greatness of their country and of the insignificance of all other lands made them so proud that the whole world seemed to them savage and barbarous compared with themselves; it was scarcely to be expected that they, while entertaining this idea, would heed foreign masters.”

“The authentic way of the Church is man: a way intertwined with profound and respectful intercultural dialogue, as Father Matteo Ricci taught us with wisdom and skill.” ~ Pope John Paul II

Soon the Chinese were evincing interest in what the Jesuit fathers had really come to lay before them: their Christian faith. The Jesuit priests were careful to show respect for their audience’s beliefs, explaining how the laws of God conform to reason and to many of the teachings of the ancient Chinese sages. After this introduction, they talked to them about the falseness of idolatry and about the love of Jesus and the promise of eternal life. For those wanting to know more about Christianity, the fathers printed a Chinese translation of the Ten Commandments. This moral code found favor with the Chinese, and thousands of these translations were distributed, along with a catechism in which the rudiments of Christian doctrine were explained in a dialogue between a pagan and a European priest.

Father Ruggieri was called back to Europe in 1588, and Ricci carried on with only the assistance of a young cleric. He experienced a setback the next year, when a Chinese official took over his house and expelled him from Chao-k’ing, but he soon set up residence in Shao-chow, where he dismissed his interpreters and began wearing the dress of the educated Chinese. After a failed attempt to enter Nan-King, he went instead to Nan-ch’ang, a city famous for its great number of learned men. There he established a Christian church and gained a hearing among the intellectuals by the deep knowledge of Confucianism that he had acquired along the way.

For the next decade, Ricci worked steadily toward his goal of gaining a hearing for Christianity in the capital city of Peking. When he was finally allowed to enter the capital in January, 1601, he befriended the emperor, Wan-Li, by repairing two small clocks for him. This and his map-making skills impressed the emperor so much that he opened doors for him, and Ricci was allowed to stay in the capital for the next 10 years while he carried on his apostolate.

Although now accepted by the Chinese and their government, Ricci drew fire from the Catholic hierarchy in his later years. Wanting to honor local traditions, he allowed his converts to carry on their tradition of burning incense in honor of their dead, concluding that it was not really ancestor “worship” but rather a way of showing respect for family members who had gone before. Ricci was criticized for this, especially by other orders that had not enjoyed his success. The affair became known as the “Chinese Rites Controversy,” and Rome took the side of the other orders and tried to curtail Ricci’s work. Peking, however, sided with the Jesuit priest, now known to them as “Li-Ma-Teu,” and he continued his work with government protection until his death in 1610.

During his 27 years in China, Ricci wrote many books and tracts that were widely used in the mission field, but the most influential was his T’ien-chu-she-i (The True Doctrine of God). Reprinted four times before its author’s death, it led countless numbers of Chinese to Christianity, and the perusal of it led a later emperor, K’ang-hi, to issue his edict of 1692 granting liberty to preach the gospel. In 2000, Pope John Paul II paid tribute to Ricci with these words: “The authentic way of the Church is man: a way intertwined with profound and respectful intercultural dialogue, as Father Matteo Ricci taught us with wisdom and skill.”

~ Leslie Hammond