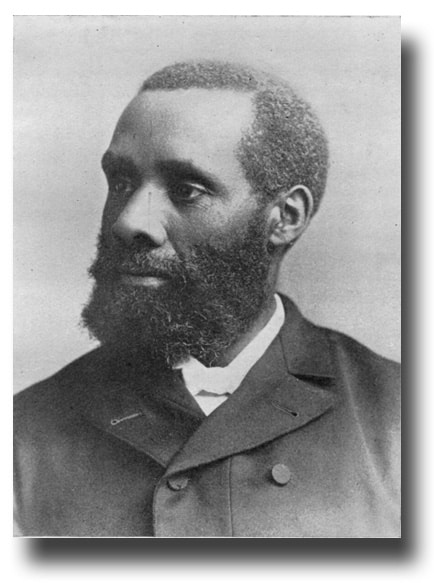

(1845-1928)

In 1879, Matthew Anderson was an energetic and ambitious young pastor on his way from Yale to the South to lead a school when he accepted an invitation to meet with Dr. John Reeve, the senior pastor of Philadelphia’s Lombard Central Presbyterian Church. Dr. Reeve wanted to meet Anderson, believing the young man was divinely equipped for a greater challenge, right there in Philadelphia, than any the South could offer. As an educated man of color who had forged a path for himself in spite of widespread systemic racism, Anderson possessed the rare gifts so desperately needed to bridge the racial gap that was widening in the North.

Thousands of African Americans were streaming north to escape the Jim Crow system and take advantage of America’s Industrial Revolution following the Civil War, only to be disappointed by inadequate housing and limited employment options. Socially conscious white leaders, trying to cross a chasm of suspicion, were failing to reach the city’s African American population.

Born in 1845 to free people of color in Pennsylvania, Anderson learned high expectations from childhood. His family owned a lumber mill and farm. From their home—a “station” on the Underground Railroad—Anderson witnessed history in the making during his teenage years. The Andersons counted back five generations of Presbyterians, members of integrated congregations that believed in the Calvinist work ethic. They taught their children to expect equality and provided Matthew a secondary education, a rarity for many Americans—of any race—at that time.

The young man attended Oberlin College in Ohio, one of the few integrated, co-educational colleges in the world at the time. Working at manual labor jobs, Anderson earned his way through college, mastering the ancient languages (a prerequisite for Divinity School), and applied to Princeton Theological Seminary in 1874. The application form did not request any ethnic identification, so Anderson did not notify them of his race. Impressed with his qualifications, Princeton accepted him, an offer that included full room and board in the seminary’s dorm. All went well until Anderson appeared at the seminary, his letter of acceptance in hand. The faculty member who greeted him hedged, proposing accommodations in the “colored” neighborhood of Princeton, but Anderson insisted on the original offer. Supported by fellow seminarians, he integrated the dorm and completed his studies there and eventually went on to earn his Doctor of Divinity at Lincoln University in 1904.

While at Oberlin College, Matthew Anderson met his future wife, Caroline Still, daughter of a leader of the Underground Railroad. While he completed his divinity degree, she became one of the first African American women doctors, graduating from the Women’s Medical College of Philadelphia. Their marriage was a partnership of pioneers.

Accepting Dr. Reeve’s invitation to serve Philadelphia’s mission of racial reconciliation with the same audacity he had applied to his education, Anderson advocated a vision for self-determination and pride for African American people. He called his vision the Berean Enterprises, and its three-pronged approach involved building a congregation, encouraging home ownership, and developing a school.

Anderson called his vision the Berean Enterprises, and its three-pronged approach involved building a congregation, encouraging home ownership, and developing a school.

When Anderson welcomed wealthy industrialists to contribute, he determined to “resolve from the very first to compel respect for himself and the congregation he represented.” He vowed that if he encountered prejudice he would “never allow an insult to pass unnoticed.” Once snubbed by a railroad executive, he wrote the man a scathing letter, saying “five hundred souls as small as yours could dance on the head of a needle.” Stunned by Anderson’s courage, the official apologized, sending a contribution.

Anderson’s first step in realizing his vision was to establish Berean Presbyterian Church, an independent congregation. Next, he undertook his mission to offer better housing to people of color. From the church basement, Reverend Anderson began the Berean Savings & Loan Association to collect savings. The first home was bought with a $1,000 mortgage.

Then he tackled education. Anderson organized the Berean Manual Training and Industrial School, starting with 35 students at the tuition of a dollar a month. Within two years the student population grew to over 300. Anderson wrote, “No people becomes strong financially which neglects the industrial training of its youth.”

Ahead of his time, Anderson envisioned a future, which he described in a speech in 1902, “when the American people will not ask whether the workman is white or black, but whether he has the qualifications and the skill to do the work required as well…as any other man.”

Matthew Anderson died in 1928. Berean Presbyterian Church still serves its congregation near Temple University.

William Allison is a retired school administrator who writes about history, religion, and travel from his home in Narberth, Pa.