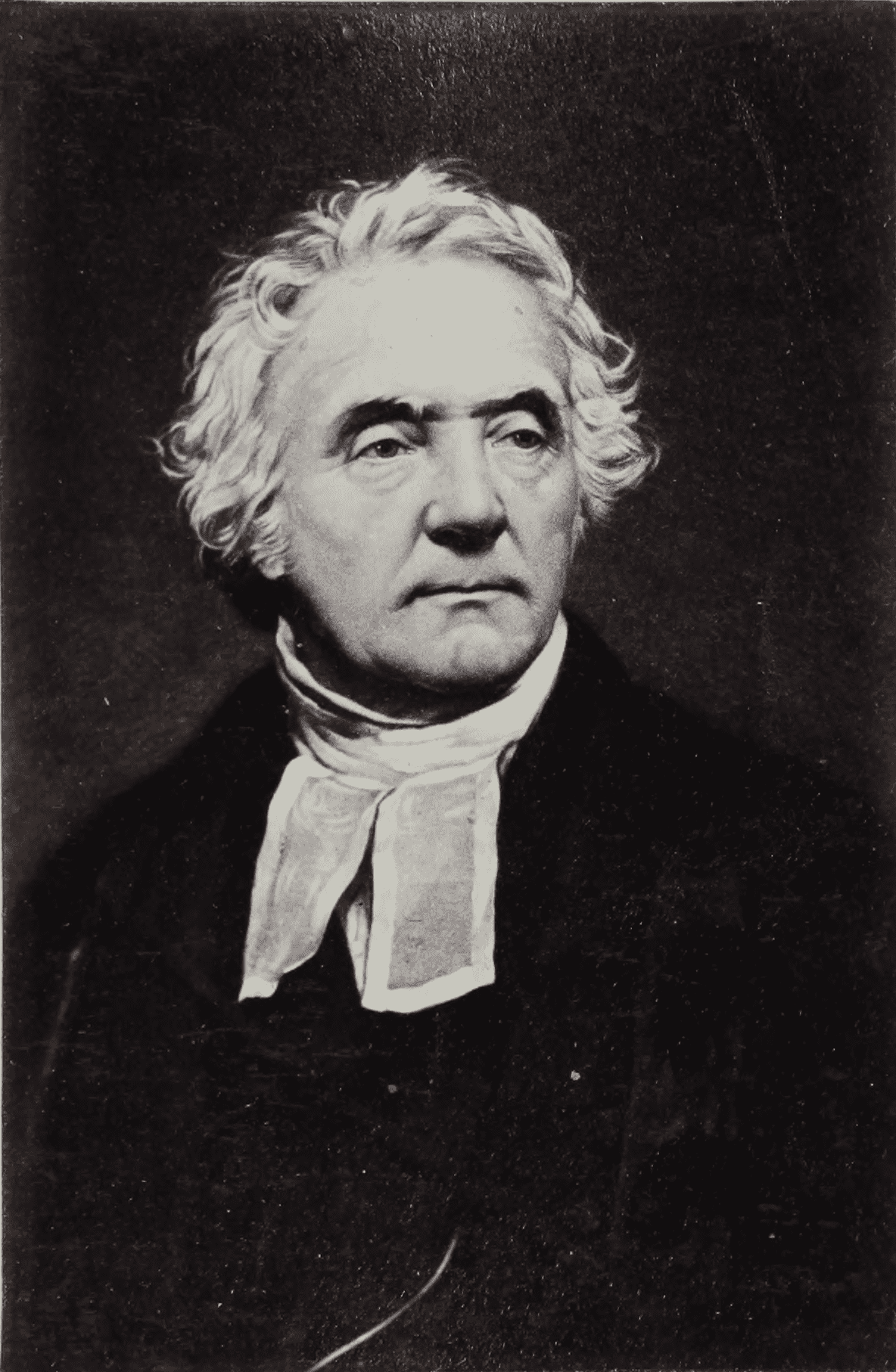

(1780-1847)

(1780-1847)

Although best known for his role in the “Disruption of 1843,” which led to the creation of the Free Church of Scotland, Thomas Chalmers was a man of diverse talents and undertakings, to each of which he brought enthusiasm, energy, and a power to arouse others to action. One biographer called him a “theologian who could speak to the man in the street.” Others cited his social projects, his powerful oratory, his gift for mathematics, and his prolific writing. There was no single occupation: Chalmers was a teacher, a preacher, a church statesman, a scholar, a social reformer, and, above all, a man who looked to the Bible as a guidebook for living.

Born in 1780 in the small Scottish fishing village of Anstruther Easter on the southeastern coast of Fife, Chalmers was the sixth of 14 children in a middle-class merchant family. His parents enrolled him at age 12 in the University of St. Andrews, where his natural enthusiasm and curiosity found its focus in the study of mathematics, politics, and ethics. At age 15 he took up a course in divinity and at age 19 graduated with a presbytery license to preach the gospel.

The ministry was put on hold while he spent two years studying higher math at the University of Edinburgh, but in 1802, after a brief stint as an assistant minister in the Scottish Borders, Chalmers was given the living of the parish of Kilmany, not far from St. Andrews. Here he managed to serve two masters, preaching at Kilmany on Sundays and working as assistant professor of mathematics at the university during the week. Although he was noted for eloquence in both roles, his sermons tended to follow the high moral tone of the day rather than stemming from any real commitment to the gospel.

After nine years of able but uninspired ministry, a bout with serious illness—coupled with the reading of William Wilberforce’s A Practical View of Christianity and Blaise Pascal’s Thoughts on Religion—finally brought Chalmers to a spiritual awakening. He realized that it was acceptance of the message of salvation that brought about real change within a person and that moral exhortations from the pulpit had “no more weight than a feather.” A new fervor came to his preaching, and people streamed from the outlying districts to hear him speak on the saving grace of Christ. He also began to demonstrate a leaning toward evangelism and became an enthusiastic supporter of Bible societies and foreign missions.

Marriage to Grace Pratt in 1812 produced a lively household of six daughters, a prolificacy matched by the writing that began to pour from his pen. Beginning with an 1813 article on Christianity in the Edinburgh Encyclopedia, Chalmers’ published works would run to 32 volumes over his lifetime. In 1815 he was appointed to the Tron Church in Glasgow, where his natural warmth and passionate preaching drew overflow crowds at both morning and evening services. A series of midweek talks on “God, Man, and the Universe” was hugely popular and sold 20,000 copies when distributed in printed form. A second lecture series, entitled “The Application of Christianity to the Commercial and Ordinary Affairs of Life,” was also printed and widely distributed.

Chalmers’ fame began to spread, and in 1817 he was invited to speak in London, where his talks were attended by prominent political, literary, and religious figures, including William Wilberforce, who had been instrumental in his spiritual rebirth. “All the world has gone wild about Chalmers,” Wilberforce wrote at the time.

Although this celebrity status led to talk of a leadership role in the evangelical faction of the Church of Scotland, Chalmers was leery of fame and spoke of the “treacherous quicksand” of popularity. Instead of focusing his attention on the fashionable people who came to hear him preach, he began to concentrate on the poor. He was keenly aware that one of the most dreadful slums in Europe lay within sight of the Tron—a place called the Calton, which was a labyrinth of dilapidated tenement buildings housing 13,000 of the city’s most impoverished citizens. Chalmers believed that parish churches should be responsible for the poor within their boundaries, and so he convinced the Glasgow Council to build him a church in the very heart of the slum. He was released from his charge at the Tron on June 14, 1819, and inducted as minister of the new St. John’s Church the same day.

Calling upon his motivational and organizational skills, he assembled a dedicated squad of elders and deacons, many of them from the Tron, whose job was to visit and reclaim the destitute, teaching them the redemptive power of Christ and the power also of self-reliance. Sabbath schools were created, and two day schools were built to supply a full education to the children. The seats of the new church were soon filled with district residents brought to active Christianity at the same time that they were brought out of the trap of poverty.

The ongoing legacy of Thomas Chalmers: The Chalmers Center is a research and training organization that equips churches around the world to empower people who are poor. By changing the way churches think about poverty and training them in practical poverty alleviation tools, the Chalmers Center supports local churches as they proclaim the gospel in both word and deed. As a result, the poor experience lasting transformation, rediscovering their God-given dignity and supporting themselves and their families.

The Chalmers Institute in St Andrews, Scotland, exists to resource and equip men and women to exercise faithful biblical leadership in the church and in society.

In 1823, worn out from ceaseless toil in the parish and assured that his well-trained team could carry on his work, Chalmers left St. John’s Parish to lecture on moral philosophy at St. Andrews. There his evangelistic spirit was influential in inspiring the first generation of Church of Scotland missionaries to India. In 1828 he became professor of divinity at Edinburgh and poured his still considerable energies into lecturing, preaching, and writing. When the Church was split by the Disruption of 1843, which came about as a result of longstanding interference by the State in church matters, Chalmers became first moderator of the Free Church of Scotland.

Just four years later, at the time of the General Assembly, Dr. Chalmers was missed at the morning session, and someone was sent to his quarters to check on him. There it was found that he had “suddenly and unexpectedly slipped peacefully away.” His funeral was the largest ever seen in Edinburgh, with thousands of his fellow Scots paying their respects as the cortege took his body to its resting place in Grange Cemetery.

~ Leslie Hammond