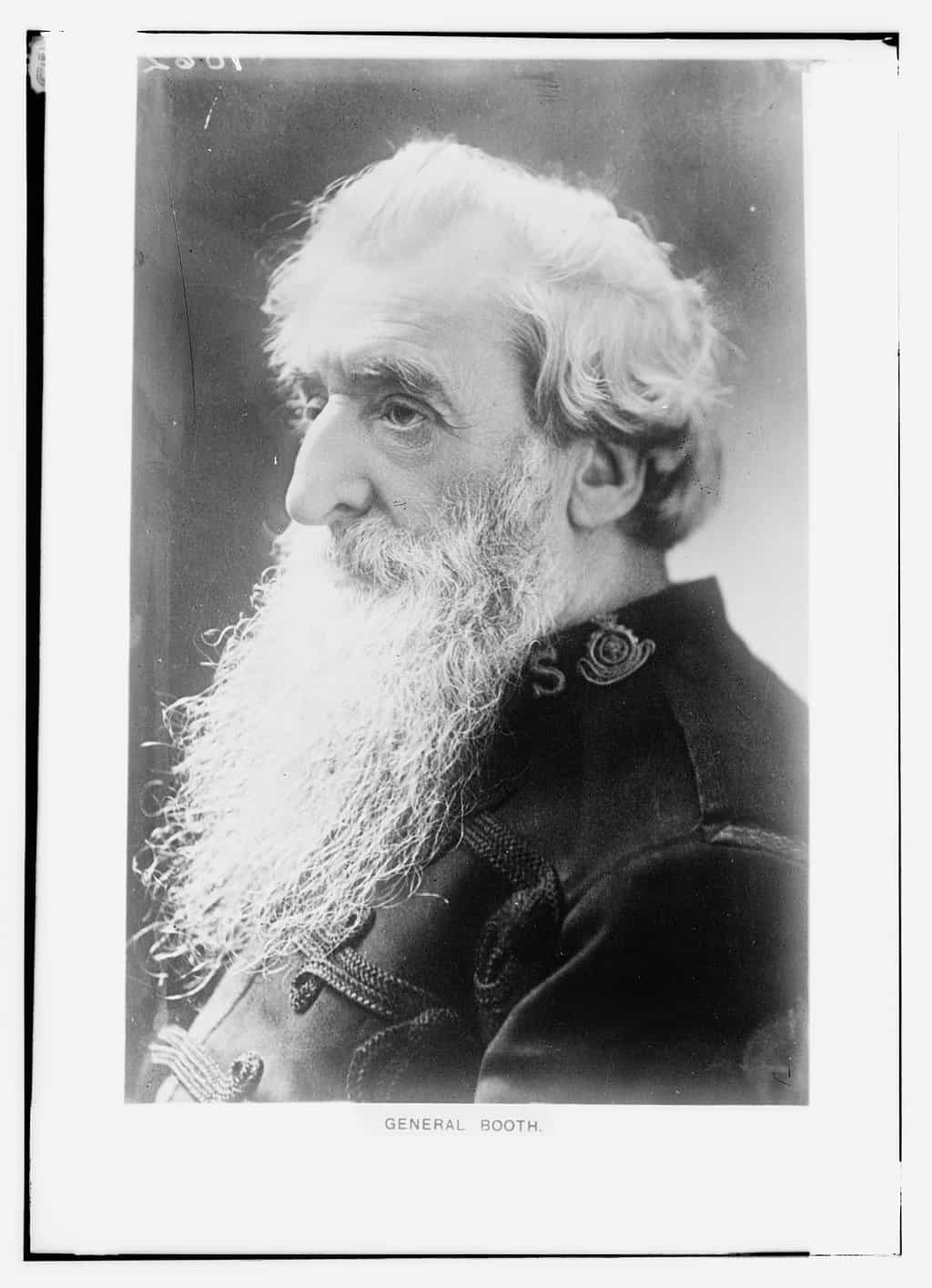

(1829-1912)

(1829-1912)

He captured the world’s imagination by putting his street-corner evangelists in military-style uniforms and sending them into town with marching bands. He gave his women members equal responsibility for preaching at a time when it was considered unseemly for the “weaker sex” to take such a role (“My best men are women!” he once said). He singled out the wrongs in British society and wrote a controversial 300-page book that outlined precisely how they could be made right.

William Booth, founder and leader of the Salvation Army, was determined to take people out of lives of degradation and bring them to new life in Christ. He believed that those who have been in the dark are often the best ones to describe how beautiful it is in the light, and many of his evangelists were the very prostitutes and drunkards he’d saved from the streets. But Booth did not reach out only to “sinners.” He was also the champion of those trapped in poverty by uncaring government and industry, and he fought in very practical ways to improve their lot.

Booth first became aware of the desperation of the urban poor when his father’s early death caused him to take a pawnbroker’s apprenticeship in his hometown of Nottingham at the age of 13. On a daily basis he saw men and women coming in to hock wedding bands to buy food for their families or to sell the coats off their backs to buy the intoxicating spirits that would numb their misery.

In 1849, at the age of 20, he moved to London to take work as an assistant pawnbroker, and there he met Catherine Mumford, the woman who would become a lifelong partner in his mission to help the downtrodden. They married in 1855, and two years later Booth, who had been converted in a Wesleyan chapel in his teens, became a Methodist New Connexion minister. His passionate revivalist style put him in constant demand as a visiting speaker, but conflicts with the Methodist establishment led him to resign from the New Connexion ministry in 1861.

Booth still considered himself an evangelist, however, and became an itinerant preacher, addressing crowds in the London streets. In 1865 two missioners observed his energetic soul-saving efforts outside a public-house and asked him to head up a series of tent meetings in Whitechapel. Later that same year he was given a modest backing to begin the Christian Mission aimed at reaching the poor of London’s East End. Booth won 60 souls his first year, but his chosen territory was a dangerous one, and Catherine wrote that he would often come home with his clothes “torn and bloody” and his head swathed with bandages “where a stone had struck.”

William Booth believed that those who have been in the dark are often the best ones to describe how beautiful it is in the light, and many of his evangelists were the very prostitutes and drunkards he’d saved from the streets.

Booth’s progress was slow but steady, and by 1867 his organization had 42 full-time evangelists and 1,000 volunteers. The real growth, however, was sparked by a simple change of name and image. While reading a printer’s proof of the group’s annual report, he noticed that his organization was described as a “volunteer army.” He crossed out the word “volunteer” and penned in “salvation,” and the group officially became known as the Salvation Army.

Workers were given ranks and uniforms, a banner was designed with the motto “Blood and Fire,” and the Salvationists marched into districts throughout London “to do battle with the devil.”Their goal of saving lost souls by bringing sinners to repentance struck a chord in the reformist atmosphere of Victorian England, and an 1882 survey showed that on a given night there were nearly 17,000 people worshiping with the Salvation Army as compared to only 11,000 in traditional churches. It was clear that Booth and his followers were reaching people that the church establishment could not.

With the Army firmly established, William and Catherine Booth used the years ahead to focus on social issues. Booth’s 1891 book about the plight of the poor, In Darkest England and the Way Out, sold 200,000 copies the first year and brought the support of several prominent businessmen.With their help, he and Catherine set up a labor bureau, purchased a farm where people could be given job training, offered meals and shelter to the homeless, established a bank that made small loans for the purchase of tools, and created a missing person’s bureau. Over the next nine years the Salvation Army served 27 million meals, lodged 11 million homeless persons, traced 18,000 missing persons, and found jobs for 9,000 unemployed.

By the time of William Booth’s death at the age of 83 the fiery evangelist saw his organization planted in 58 countries. Today it serves people in nearly twice that many nations.

~ Leslie Hammond