As someone who is a member of the Reformed branch of the conservative evangelical church, I have been asking myself what I would like to see happen in the future for us straight Christians who hold to a Side B position on homosexuality. By Side B, what I mean is the view that God’s original intention at creation was for the marriage union to be between a man and a woman. How can we hold to our beliefs in a way that is more true to the Gospel of Jesus Christ and less true to our own fears, prejudices and human agendas?

Some years back when I was first seeking to hang out with more LGBT Christians, I realized my conservatism was going to be a problem. I didn’t want to bear a label that would make people feel uneasy, and being straight and Side B might shut down conversation before it could even get off the ground. So one day, feeling pretty stressed out about the whole thing, I just decided I was going to be Side A. No study or anything—I just wanted to be affirming. That way I could label myself as something that said to LGBT people, “See, I’m not hurtful, I’m not threatening.” Besides, there were a number of aspects to the affirming view that I found appealing.

Some years back when I was first seeking to hang out with more LGBT Christians, I realized my conservatism was going to be a problem. I didn’t want to bear a label that would make people feel uneasy, and being straight and Side B might shut down conversation before it could even get off the ground. So one day, feeling pretty stressed out about the whole thing, I just decided I was going to be Side A. No study or anything—I just wanted to be affirming. That way I could label myself as something that said to LGBT people, “See, I’m not hurtful, I’m not threatening.” Besides, there were a number of aspects to the affirming view that I found appealing.

That experiment lasted only about two months. I was having trouble meshing the Side A view with my broader understanding of the Bible, in which I see a Creation-Fall-Redemption-Consummation progression. To my understanding, the doctrine of the Fall sets the stage for our need for redemption, becoming the occasion for God to show his love for us so dramatically by sending his Son. So it is tied in with my understanding of the Gospel message. I currently understand same-sex sexual orientation as fallen, but not sinful. “Fallen but not sinful” is about the best way I can describe something that, I have found, seems to defy all theological categories and language.

In the end, I decided to embrace the Side B label for simplicity’s sake, and yet I’ve always been torn between the two views, Side B and Side A, because both seem to have legitimate things to say about how gay Christians should practically live out their lives. I’ve become friends with godly gay Christians on both sides of the debate.

The apostle Paul recognizes in the fourteenth chapter of Romans that there are certain issues on which Christians will take opposing sides, yet both sides are able to hold their position in good conscience. He says the key to having a good conscience is faith. In Romans 14:22-23 Paul writes, “The faith which you have, have as your own conviction before God. Happy is he who does not condemn himself in what he approves…whatever is not from faith is sin.”

The Apostle Paul says the key to having a good conscience is faith.

Because Side B gay Christians believe God originally intended marriage to be between a man and a woman, they seek to honor Christ by embracing the vocation of celibacy, or by being faithful in a mixed-orientation marriage, or by seeking out deeper friendships within the church. That takes faith. Side A gay Christians believe God created them to be gay and that there can be nothing sinful in loving another human being. They seek to honor Christ by being in a loving, committed same-sex relationship. That also takes faith. There are gay Christians on both sides who have confided in me that they wonder if it’s really the other side that is correct, yet both Side B doubters and Side A doubters put themselves in God’s hands trusting that he will lead them in the right path. That is yet another expression of faith.

Considering the theological issues, the human issues, and the conscience issues involved, we will never be in total agreement, yet we can still recognize the Christian unity we all share even in the midst of our diverse experiences and viewpoints. So when I think about what’s next for the conservative evangelical church, that’s the direction I would like to see us head. I would like to see us work toward greater unity even amidst our disagreements over faith and sexuality.

That could be the end of this article, but I realize that I have only raised more questions: Why aren’t conservative evangelicals headed in a more understanding and reconciling direction? Why do evangelicals say similar stuff to what I’m saying about the Fall, redemption in Christ, and walking by faith, yet instead of seeking greater Christian unity, they draw a line in the sand, treating LGBT people with attitudes that range from cold aloofness to open hostility?

To answer that question, I’d have to talk about where I think evangelicals have been in the past, where they are right now, and why we haven’t moved toward a more conciliatory relationship with the LGBT community. And although I say “LGBT,” I regret that I don’t have much to say that even would be relevant to bisexual and transgender Christians, not to mention those who identify as queer, intersex or asexual. The fact is, the conservative church is still only talking about the L and the G, and isn’t even having conversations about the other identities. Or, if there are such conversations, they haven’t reached a level decent enough to be worth mentioning.

I’m not an ordained minister; I do not hold an ordained office of any kind. I’m just a layperson with some theological education who serves faithfully in my church while being a wife and stay-at-home-mother. I offer you the following as my personal observances.

Slogans v. truth

I remember a time, particularly in the 1980’s and ’90s, when all I ever heard from evangelical pulpits in America was that homosexuality was a “sinful lifestyle choice.” The explanation for the existence of gay people went something like this: They were people who at some point in their lives, whether out of naïve curiosity or driven by perverse lust, engaged in same-sex sexual behavior against their natural heterosexual desires. They then became addicted to this lifestyle and soon made themselves so abhorrent to God that he “gave them over” to their lusts so that they could no longer turn away from their chosen lifestyle. In other words, they were a category of people who were beyond redemption, and so words like “depraved” were thrown around liberally to describe those who apparently fell into this fearful spiritual condition.

As these ideas were being accepted without question in the church, there was another movement that was also gaining some ground, though more quietly and gradually. Ex-gay ministries were beginning to grow in prominence and popularity. And as these ministries seemed to thrive, it became increasingly difficult to explain why so any people who were supposedly choosing to be gay were at the same time choosing to join ministries that promised to make them straight. Why people who were supposedly beyond repentance were flocking to ministries that would help them do something so repentance-like. So many terrible tragedies came out of ex-gay ministries, and yet the temporary popularity of these ministries also effectively called into question some of the worst accusations leveled by straight conservatives at gay and lesbian people.

Now, when the conservative church gets the feeling that they might have been wrong about something, we don’t apologize. Instead we shift ground. We tell ourselves we’re still basically right, we’re just fine-tuning, and we kind of pretend that we never made some of those outlandish statements in the past, even though we tolerate perfectly well those who continue to make them.

Around the early 2000s I began hearing a new slogan circulating among evangelicals that went something like this: “Even if being gay isn’t a choice, how you act upon it is.” The idea is: “See, we’re not giving up on the idea that it’s a choice, we’re just saying if it’s not a choice. And even if it isn’t a choice, we still reserve the right to point out the obvious, which is that you have to make good choices about what to do with your gayness.” What is considered a good choice? You may ask. Church leaders directed people to the options advocated by ex-gay ministries: Seek orientation change, and if possible enter into an opposite-sex marriage. There’s also celibacy, but that option was viewed as only half-satisfactory.

As the years passed on, an increasing number of ex-gay leaders became ex-ex-gay leaders, and one ex-gay ministry after another began admitting their low to non-existent success rates in changing people’s sexual orientation. Even as the former leaders of these ministries were stepping forward and apologizing for the damage done, it is telling that most straight Christian leaders who had once supported them turned their backs on them for not keeping the faith. Yet there is no doubt that, currently, we are at a place where we can say that the hey-day of ex-gay ministries is over.

And now, just as before, an old slogan has been abandoned for a new one with hardly an explanation given. These days I’ve been hearing a saying that goes like this: “You shouldn’t call yourself gay, because your identity is in Christ.” Another version I hear: “Calling yourself a gay Christian is an oxymoron.” I’m still trying to figure out why so many in the church have latched onto this mantra, as if getting it wrong on the issue of choice and getting it wrong on the issue of change somehow puts us in the credible position of now being able to dictate to gay people about such a personal matter as what to call themselves. My guess is that because the label “ex-gay” has fallen from grace—and this was the one label conservatives felt comfortable using—the only thing left to do is attack the term “gay,” even though I don’t hear anyone suggesting any viable alternatives.

What healing can softened language and a change of emphasis bring when our original claim—that homosexuality is a chosen lifestyle driven by spiritual rebellion and unnatural lust—has never been officially taken off the table?

Given all the slogan changes, the thinking of the evangelical church about homosexuality appears to have made some progress, but it seems to me that progress has been superficial. The public face of evangelicalism has softened its language, and many leaders are now putting more emphasis on the need for love instead of beating the drum of condemnation. But what healing can softened language and a change of emphasis bring when our original claim—that homosexuality is a chosen lifestyle driven by spiritual rebellion and unnatural lust—has never been officially taken off the table? How is simply making adjustments in our language an appropriate remedy for having made the kinds of accusations that destroyed family relationships, ruined reputations, stripped people of their faith, crushed their hope, and in some tragic cases, compelled people to take their own lives? I am aware of no public apology articulated by the conservative evangelical church, nor of any significant acts of repentance that we have performed collectively, to show that we have made a clean break from the many false accusations we have leveled against gay and lesbian people for so long in our recent history.

We have taken half-measures to deal with this situation, telling ourselves we are okay because we have embraced what is supposed to be a kinder, gentler brand of evangelicalism. For example, I’ve noticed these days that some straight Christians will take care to emphasize that all of us, whether heterosexual or homosexual, are sinners who need to hear the gospel message. They may even go as far as explaining that sometimes hearing the truth about our sin may come off as hurtful, but it is meant to be loving and should not be taken as hatred of gay people but as speaking the truth in love. Yet when these Christians say they are “speaking the truth in love,” what do they understand to be the truth about homosexuality? Because if that understanding isn’t accurate, then what one has to say could hardly qualify as loving, no matter how loving a tone is used to speak it.

When it comes to exercising Christian love, we so easily convince ourselves that being loving has to do with our own good intentions and wanting the best for the other person according to where we think they should be at spiritually. What we don’t always take care to examine is the content of what we’re saying, whether it is factual, whether it is accurate, or if it even makes any sense at all to another person’s life.

What we don’t always take care to examine is the content of what we’re saying, whether it is factual, whether it is accurate, or if it even makes any sense at all to another person’s life.

I have heard some straight Christians say in a very sympathetic tone, “You know, we’re all sinners, and homosexuality is just another sin.” And then they would add, “Like murder.” Now, how does loving a person of the same sex even compare with taking someone else’s life? Or I would hear people say that they view the same-sex marriage issue just as they would any sexual sin, like adultery or fornication. And yet, how are these valid comparisons when you consider that same-sex marriage is the formation of a committed relationship, whereas adultery is a betrayal of that commitment? Fornication is sex outside of marriage, whereas same-sex marriage allows for sex inside of marriage.

Many straight Christians have come to understand that being gay is about having same-sex attractions and doesn’t necessarily mean that one is sexually active. But then I hear them characterize same-sex sexual attraction as a temptation that must be continually struggled against. All Christians struggle with temptation, they say. As for those who have same sex-attractions, what we are requiring them to do is no different than what any Christian is required to do in their daily struggle against sin.

But here is my problem. A struggle against temptation implies that a battle must be fought to return things to a state of normalcy. Insisting that same-sex sexual attraction itself should be viewed as a temptation to be continually struggled against raises the question of what gay Christians should be struggling to achieve? What does victory look like should they succeed?

Should they rid themselves of all sexual feeling whatsoever, only to replace it with nothing, to exist in an emotional vacuum? Straight Christians don’t think that’s what they’re saying, but in reality that’s the only conclusion many gay Christians can practically come to. I’ve seen people throw themselves into work, into various addictions, and into despair and destructive behaviors because they felt they weren’t allowed to feel and exist as sexual beings. They were being asked to do something humanly impossible.

Or are we saying their struggle should lead them to becoming heterosexual? That is just another road back to ex-gay therapy. Yet our nearly four-decade experiment with ex-gay ministries ought to have shown us how wrong we were about people’s ability to change their sexual orientation. Imagine for a moment what would happen if there were a government-funded experiment that ran for nearly four decades. This experiment utilized a sample size of participants that reached into the thousands, maybe even tens of thousands, all of whom are highly motivated and who had everything to gain in seeing the experiment succeed. Yet in the end, experts estimated the failure rate to be around 99.9%. Now suppose some government officials still insisted on continuing the program because they thought the participants hadn’t been trying hard enough to succeed. Wouldn’t there be the biggest public outcry over the blindness and the stupidity and the waste of taxpayer money, with memes sent around everywhere and social media about to explode?

Evangelical Christians need to realize that our failed experiment with making gay people straight ought to result in a major paradigm shift in our thinking. It means admitting that we were wrong about so many things. It means repenting. And repenting means changing our ways and changing our thinking. It means making a clean break from the old threads of thought and starting someplace new.

I would suggest that the most helpful place for the conservative church to begin anew is by thinking of homosexuality as simply a sexual orientation. Because sexual orientation is something that applies to all people. I have a sexual orientation; you have a sexual orientation. We differ in our respective orientations, but what we have in common is our human sexuality. Those of us who are Side B may believe that the existence of same-sex sexual orientation is a result of the Fall, whereas those who are Side A may believe that God created people to be gay. But whichever view you hold to, we should be able to agree that aside from differences in orientation, gays and straights both experience sexuality in the same way. That is why the best analogy you can use to understand homosexuality is not adultery, not fornication, not struggle or temptation. The best, most useful analogy you can use to understand homosexuality is heterosexuality.

The best, most useful analogy you can use to understand homosexuality is heterosexuality.

I have heard a lot of stories from my gay friends about what it was like when they first came out to friends or family members. Often the first question they were asked is, “How do you know you’re gay?” Interesting, because I don’t think anyone has ever asked me, “How do you know you’re straight?” I would bet that most straight people have never been asked that question.

How do I know that I’m straight? It’s because I feel an attraction toward men—not all men but certain men—and it’s something that I never feel toward women. You can call it attraction, appreciation, fascination. It’s not just a good feeling toward that other person but something that reflects back and makes me feel good about me. I first noticed it in elementary school. I was around 10 years old, and I kept noticing a boy who was a part of our neighborhood carpool. He and his family had just moved in next door, and sometimes my older brother would go to his house to play basketball. Now, I wasn’t one of those girls who viewed crushing on a boy as some fantastic emotional wave to be riding high on. I felt threatened by it. I had no idea where these ridiculous feelings came from, and I also found it confusing that some boy would have that kind of effect on me when I didn’t really know him that well. In fact, there was nothing he or I did, as far as I could tell, to cause this to happen.

As the years passed and I made my way through my teens, I repeated the same pattern through various other crushes—boys in high school I took classes with, the young men I met at college Christian fellowship groups. I knew how to exercise self-control, but I also began to understand that sexual feelings are not something that can be ignored or switched off. It was something I needed to understand about myself, and I was well aware that my friends were going through it too.

So did I choose to be straight? Does it sound as if I made a choice there when I was 10? Am I pushing my sex life in your face by talking about this? But you see, I haven’t talked about sex, I haven’t mentioned having sex. I’m talking about my feelings of attraction toward the opposite sex and how I first became aware of them. All I’ve talked about was my sexual orientation.

People who try to explain their sexual orientation are going to tell stories similar to mine, and thousands of these stories have already been told. But as a straight person you sometimes don’t recognize that if you were to tell your story of your first opposite-sex crush, it isn’t going to sound a whole lot different from the story of someone explaining how they first knew they were gay or lesbian. This recognition is the starting point not just for conversation but for relating, for understanding just how parallel our experiences are.

The best definition I have found of what it means to be gay or lesbian is in R. Holben’s book What Christians Think about Homosexuality. He writes:

Most importantly, in referring to the gay, lesbian or homosexual person…I will be speaking of [someone] in whom not only the sexual drives but also the deepest emotional and psychological urges for self-revelation, intimacy, and connectedness, bonding, closeness and commitment—all that we call romantic/erotic love—find their internal, spontaneous fulfillment not in the opposite sex but in the same sex.

It’s a definition that heterosexuals can relate to as well.

Most straight conservative Christians I know view Side B gay Christians as second-class citizens and Side A gay Christians as not Christian at all. But understanding who gay Christians are in light of Holben’s words should cause us to esteem those who are Side B as living by a sexual ethic that far exceeds what we expect from ourselves, as well as to recognize that those who are Side A have desires and goals for their lives that are the same as our own.

The Bible v. the Bible

I have spent all this time explaining how I think straight evangelical Christians should view homosexuality, and yet we all know perfectly well why the majority of them would respond to my proposal with anything from reluctance to outright rejection. It can be summed up in two words: The Bible.

The Bible seems to give a different presentation of people who seek after or engage in same-sex sexual relations. There is the story of the lustful men of Sodom. There are the abominations of Leviticus. There are the condemnations of Paul in Romans 1, 1 Corinthians 6, and 1 Timothy 1. Those of you who have studied these passages in depth know that in these last two passages the highly debated Greek term arsenokoitai is listed with many of the heavyweight sins: fornication, idolatry, adultery and murder. So, in spite of living at a time when so much exposure to the stories and perspectives of gay people ought to make you think twice, many straight Christians will still automatically compare gay relationships with these heavyweight sins because the Bible seems to do it. When you have the inspired, inerrant, authoritative Word of God on one hand against the subjective experience of fallible people on the other, it’s obvious which one you go with. You go with the Bible.

I’m trying not to be dismissive of that choice, as if “going with the Bible” is always done out of brainlessness or blind orthodoxy. For all Bible-believing Christians, whether gay or straight, we know it’s much deeper than that. The word of God is closely intertwined with our own spirituality. As you grow and mature as a Christian, your understanding of the Bible, combined with years of learning to walk with Christ by faith, teaches you to reflexively and instinctively interpret the things we see and experience in the world through the lens of a biblical understanding.

There are thousands of examples of how we look to the Bible for encouragement and a spiritual perspective. The Scriptures are like lenses that we hold up in front of near-sighted eyes so that by faith we can see God’s truths more clearly. For instance, when I feel like violence in the world is escalating out of control, I pick up my Bible and read, “The LORD reigns, let the earth be glad” (Ps. 97:1). It doesn’t feel as if God is reigning, but it must be true because the Bible says so, and I need to adjust my perspective accordingly. When I see people victimized by those in power, I read, “The LORD performs righteous deeds, and judgments for all who are oppressed” (Ps. 103:6). It doesn’t seem like God cares for the oppressed, but I trust that he does, because the Bible says so.

And so what happens? You read something in the Bible that has to do with same-sex sexual relationships and you figure this must be the real truth about homosexuality, even if gay people are saying otherwise. Nothing is more natural to the evangelical Christian than to interpret human experience through the lens of Scripture.

Nothing is more natural to the evangelical Christian than to interpret human experience through the lens of Scripture.

There are examples in church history when we realized the direction of the interpretive lens needed to be reversed, where human experience and observation informed and clarified our interpretation of Scripture. Most famously, Galileo’s defense of the Copernican Theory that the earth revolved around the sun seemed to contradict biblical passages that appeared to say God had established the earth as a stationary body. Yet over time we learned to interpret those passages metaphorically to accommodate a heliocentric understanding of the solar system. So even though that isn’t the usual interpretive direction we take, there is precedent for adjusting our understanding of Scripture rather than our understanding of what we observe in the world.

At this point someone might object: Well, it is one thing when scientific observations are being made using a telescope, but how can that be compared with having some conversations with gays and lesbians about how they experience their sexual orientation? Their experience isn’t objective scientific fact. It is just the self-report of sinners, and just like any sinner they would be motivated by self-interest. They may be tempted to make their sin look better than it really is. Or they may be influenced by worldly ideas from the secular gay community. Or maybe they are just rebelling against the Word of God and don’t really care what it says. How can you possibly justify putting more weight on fallible human testimony versus the infallible testimony of Holy Scripture?

Here’s how: Because when you start listening to the stories of gay people and forming meaningful friendships, the real dilemma you run up against is much worse. The dilemma is not the testimony of gay people versus the testimony of Scripture. The real dilemma is the application of Scripture versus the testimony of Scripture. Application versus testimony. What do you do when applying the biblical command to love people leads to you the conclusion that the Bible seems to be portraying those people in a worse light than they deserve? That is the true dilemma. It’s really the Bible versus the Bible.

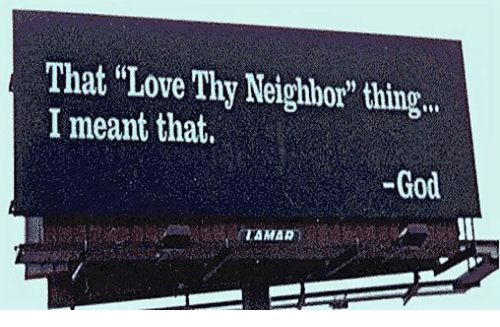

Both the Old and New Testaments teach that the way you love your neighbor is by being as concerned for him or her as you would be for yourself. Leviticus 19:18 says, “Love your neighbor as yourself.” In Luke 6:31 Jesus reiterates the same teaching when he says, “Treat others the same way you want them to treat you.” By wording these commands in this way, the Holy Spirit is instructing us to use our own standards for how we would want to be treated as a reference point for how we should relate to others.

To accomplish this you have to put yourself in the other person’s shoes. You have to imagine yourself as that person, in that situation, dealing with their particular challenges. You may have to interact with that person in a way that draws them out to give you insight into what their perspective and situation and challenges are. Then you ask yourself, ‘How would I be feeling if I were them? How would I want to be understood? What kind of response would I need if I were in their shoes?” Then you have to pull back into yourself and try to give that person what they need based on what you have understood from going through that process. All these steps are implied when you unpack these simple biblical commands to love that are so familiar to us all and so central to our Christian faith.

If straight Christians were to love their gay brothers and sisters in Christ like that, there would probably be no need for an organization like the Gay Christian Network, because the regular old church would be doing its job. So why don’t we love like we’re supposed to? I have even heard some conservative Christians speak of love somewhat cynically and even disparagingly, as if love is the mushy watchword of those who have no interest in doctrine and objective truth.

I have even heard some conservative Christians speak of love somewhat cynically and even disparagingly, as if love is the mushy watchword of those who have no interest in doctrine and objective truth.

Perhaps we say this because we already sense that heading down this path of love could lead us to conclusions about homosexuality that would put us at odds with what the Bible seems to be saying. To avoid this conflict, we withhold the full-measure of empathy from our gay friends, family members or acquaintances, because we don’t want to get sucked into their perspective. We must discover homosexuality to be deviant and disordered. If we aren’t seeing it that way, it must be because gay people aren’t telling us everything, or they aren’t trying hard enough to see their condition for what it is, or because their disorder is so deeply entrenched only God sees it, but we know it’s there. We stockpile an arsenal of protests and arguments to unleash upon our own minds whenever we feel that dangerous empathy coming over to us. The empathy that could derail us from the truth.

But is that approach true to Jesus’ command about how we should love one another? He said, “Treat others the same way you want them to treat you.” And so you are obligated to ask: How would I feel if I were trying to explain a deeply personal experience to someone who did not share that experience, and that person dismissed what I had to say as either a lie, a product of self-deception, a delusion, or proof that I lacked faith—all because they had a prior commitment to a set of theological beliefs?

I once had a gay atheist friend, now deceased, with whom I shared many common interests. He was very decent when it came to discussing religion, yet I knew that, privately, he viewed Christians who claimed to have a relationship with Jesus Christ as, essentially, suffering from a psychosis. Sometimes I’d wonder about that. I’d be thinking, “He’s gotten to know me pretty well. Does he really think I’m psychotic? Does he really think I’m the kind of person to just make up stuff about relating to a deity?” I never really knew for sure, but I learned from that experience that when someone has decided to believe something about you—regardless of what their interactions with you should have told them about your true character, and it’s all because they have a prior commitment to a certain belief system—it sure is hard to have a meaningful relationship with them. You certainly would not say you feel loved with the love of Christ.

I think that many straight Christians know, deep down, when they are withholding from gay and lesbian people the full measure of Christ’s love, but they do it out of devotion to God’s word, to shield it from being questioned, from being possibly wrong, and it seems like a noble and justifiable reason. What it boils down to is that they are afraid to obey God’s command to love fully because they fear it may open the door to discrediting God’s word.

They are afraid to obey God’s command to love fully because they fear it may open the door to discrediting God’s word.

There was once a man who found himself in a similar dilemma. In fact, it was far worse. It was a situation where, if he obeyed God’s command, he would destroy God’s promise. God promised Abraham that he would make him into a great nation, and he would accomplish this by giving him a son. Isaac was the embodiment of all that God had promised. Kings and nations would come from him. Through him, Abraham’s descendants would become as numerous as the stars of the sky and the sand of the seashore. Everything Abraham had hoped for and suffered in his long and painful life was worth it because God had fulfilled his promise by giving him Isaac.

Then one day, when Isaac was only 12 years old, God came to Abraham and commanded him to take his son and offer him as a burnt offering on one of the mountains of Moriah. Now Abraham was faced with the mother of all dilemmas. If he obeyed God’s Word, he would destroy all the promises of God through Isaac.

In his younger years Abraham might have argued with God, tried to bargain with him, or tried to take a shortcut through the dilemma. But this was the mature Abraham, and he considered no such schemes. As soon as he received God’s command, he got up early the next morning, saddled his donkey, collected some wood, took Isaac, brought along a couple of servants, hiked the mountain, bound his son on the altar, and raised his knife to slay him.

I’m sure you remember how the story ended, but if you don’t, look it up. It’s in the book of Genesis, chapter 22.

The point we are interested in is this: Why did Abraham obey so immediately, so decisively? Didn’t he fear destroying the promised son? Wasn’t he distraught over the apparent contradiction? Wasn’t he cognizant of the disaster his obedience to God’s command would bring about?

Sure he was, but his attitude was: Not my problem. It’s not my job to resolve whatever disaster or apparent contradiction results from obeying a clear command from God. That’s God’s problem. My job is to obey.

And so it is here.

Loving gay and lesbian people the way God commands may lead to problems in our understanding of certain Bible passages. It may also lead to problems with seeing eye to eye with our fellow Christians, with preserving our good name in the church, with staying employed at the Christian organization where we work, or with knowing what’s up and what’s down anymore in the Christian life in general. But if we are going to have to face these problems, at least we can do it with confidence of knowing we are obeying God’s clear command.

One thing I do know: God does not command us to love in order to undermine the Scriptures, compromise the truth, blind us from discerning sin, drive our faith over a cliff, or whatever the imagined spiritual consequences may be. Even if those consequences seem inescapable, we still need to trust him as fully as Abraham did. I’m sure Abraham felt like he was driving his faith over a cliff. Yet he got in that car, turned on the ignition, put in in gear, and floored it. What is faith if not obeying in the face of your fears?

Everyone thinks the problem with evangelical Christians is that we believe the Bible too much. I don’t think so. Our real problem is that we don’t believe it enough.

Everyone thinks the problem with evangelical Christians is that we believe the Bible too much. I don’t think so. Our real problem is that we don’t believe it enough.

Author Robert Brault said, “Today I bent the truth to be kind, and I have no regret, for I am far surer of what is kind than I am of what is true.”

We evangelical Christians believe in objective truth. We are desperately interested in knowing the truth, presumably so that we can obey it. But perhaps God is showing us how we have made an idol of pursuing truth, and the proof is that we seem to be more interested in being right than in being obedient. It is possible that God is deliberately keeping the answers we want just out of reach, so that we would be forced to return to the true things we do know: that loving one another is the second greatest commandment next to loving God, that love is the fulfillment of the law, and that this is love, not that we loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the propitiation for our sins. Beloved, if God so loved us, we also ought to love one another.

Misty Irons is a blogger, wife, and mother of three. She has been writing about the relationship between the conservative church and LGBT community for the past 15 years. She has a masters in Biblical Studies from Westminster Theological Seminary, California. In 2002, her essay “A Conservative Christian Case for Civil Same-Sex Marriage” sparked widespread controversy within her very conservative denomination. After 18 months of debate, discussion, and judicial proceedings within the ecclesiastical court, she and her husband, Rev. Lee Irons, were forced to leave the denomination and disband the church they had been planting for 10 years.

This article is adapted from the plenary she gave at the 2016 Gay Christian Network Conference. It is reproduced here by her kind permission. (You can read/share this article in Spanish!)

13 Responses

The question I’ve been asking in the past few days (and the reason I read this article) is Does God speak conflicting moral “truths” to his children? My assumption is that this is impossible. If my brother and I are honestly and sincerely asking God to reveal the truth of Scripture about a moral issue that must be either right or wrong, and I say God tells me Yes while my brother says God tells him No, then one of us isn’t hearing from God. That means one of us is hearing, listening to and identifying another voice as “God”. So my brother and I are hearing different voices. God does not contradict himself, so I have to reason that one or neither of us is hearing from God, while one or both of us is hearing from a false god. But we both cannot be hearing from God. Assuming one of us is hearing from God, how can the true follower have unity with someone who is following the voice of a different god? Unity of the Body of Christ is important. But are people who follow a voice that is not God really a part of the Body of Christ? I just don’t see how it can be.

Thank you, Scott. I too ask this question! Why, if we are all informed by the same Holy Spirit, do Christians disagree on so many issues? Whether women should be welcomed into or excluded from leadership, whether we should embrace or ban divorced people from our denominations, whether we should condone a “just” war or refrain from any form of violence. It’s hard to know what God makes of all our disagreements and various interpretations of what the Bible is really calling us to in each and every situation and on every issue. I find Eugene Peterson’s expression of the difficulties of church (in his book Practicing Resurrection) particularly compelling:

“I want to look at what we have, what the church is right now, and ask, Do you think that maybe this is exactly what God intended when he created the church? Maybe the church as we have it provides the very conditions and proper company congenial for growing up in Christ, for becoming mature, for arriving at the measure of the stature of Christ. Maybe God knows what he is doing, giving us church, this church.”

There is much pain in the divisions the church manifests. But in each conflict lies the possibility of Christ polishing us through the rub. May we continue to seek Christ’s truth, live in and out of our convictions, but never forget to follow one of Christ’s greatest commands: to love each other as we love ourselves. Given that there IS disagreement, how do we love each other well amidst that? If we each dig in and day “I’m right, you’re wrong,” what does that look like? Is there a way to love that doesn’t diminish our deepest convictions?

Wow, that’s a really interesting thought. I have often said that it’s arrogant for a person to assume that they are correct in their theology and interpretation of scripture, but when the question is re-framed as hearing the voice of God and/or the prompting of the Holy Spirit, it takes on new meaning. I guess in that context, I would say that we need to be cautious when we hear the voice of God. Perhaps in some situations, God may say yes to one person and only respond with silence to another who, believing he knows what God sounds like, imagines that he hears a no.

Irons is right to turn our attention to Scripture and the apparent contradictions there, and Komarnicki is right to remind us that the Spirit is present at precisely those places, enabling the church to see what appeared to be a contradiction as a paradox.

But I find Irons’ description of the tension (we are to love AND we are to oppose same-sex activity) to miss the mark. Better, I think, to describe the apparent contradiction in a way that isn’t quite so subjective: the church is to welcome those seeking to follow Jesus AND the church is bear witness to the wisdom of God’s creation.

Misty Irons sets forth important points on orientation. I would add that Christians should affirm SSA members who share affectionate lives within their orientation. Such people contribute gifts into the Church.

The elephant in the room that is avoided in these discussions, it seems, is the issue of actual homosexual intercourse. For males, this might involve anal penetration. There are many who think such an act is disgusting, and therefore display animus toward practicing homosexuals.

Marriage in various forms has existed throughout history in all cultures. From an anthropological perspective, marriage solidifies a given society by protecting sexual exclusivity, thus deescalating violent male competition. The animal kingdom gives plenty of examples of violent sexual competition, nature’s way of bolstering the genetic line. Human societies, thankfully, have survived due to marriage.

Same sex marriage, then, is a new social experiment based upon an evolving redefinition of marriage based upon intimate affection rather than traditionally maintaining a lineage through progeny (which often involved strengthening inter-tribal bonds, etc.).

David and Jonathan had a deeply affectionate, soul-intimate relationship. Numerous Christians throughout history have and do find such relationships within monastic communities, religious orders, and shared families. Celibately. The celibate life has always been the calling for single Christians irrespective of orientation. The God-given need for soul-intimacy must be met, and tragically, the western Church tends to be highly individualistic. An affirming Church will nurture affection while safeguarding sexual exclusivity and discipline. It’s a tall order that scripture is clear in its calling.

I can’t thank you enough for this article. I have read it aloud so I could HEAR it. In 1964

I married a loving man, had a child and came to understand he was gay just 4 years later.

I have struggled as an evangelical believer, read, listened, shared my story, but this is the

best I have read. Thank you, deeply. This gives me encouragement, confidence, that what

I have believed and walked thru has truly been in the loving arms of my Lover, not matter

what the labels surrounding my journey.

Thank you! The piece reveals that you’ve invested heavily in the lives of gay friends/family, enough to listen, hear, and understand. You get it. Finally, something from a fellow Christian who doesn’t discount me because of what they don’t like about me. I’m blessed. I’ve posted the article at my blog: http://www.lifeincocoon.wordpress.com.

There is much discussion about homosexuality and the church. I would like to see a biblical approach to homosexuality explained by a Gay Christian to help me understand the issue. I am a heterosexual and have worked well with Gays, but I struggle with the changing perspectives, though I am glad that LGBTs are being shown more love than they used to, which to me was very un-biblical.

We would recommend Oriented to Faith by Tim Otto, Torn by Justin Lee, and God and the Gay Christian by Matthew Vines.

This is, by far, the best and most thorough and nuanced article I have ever read about this topic. Thank you, thank you.