Originally published 16 February 2021

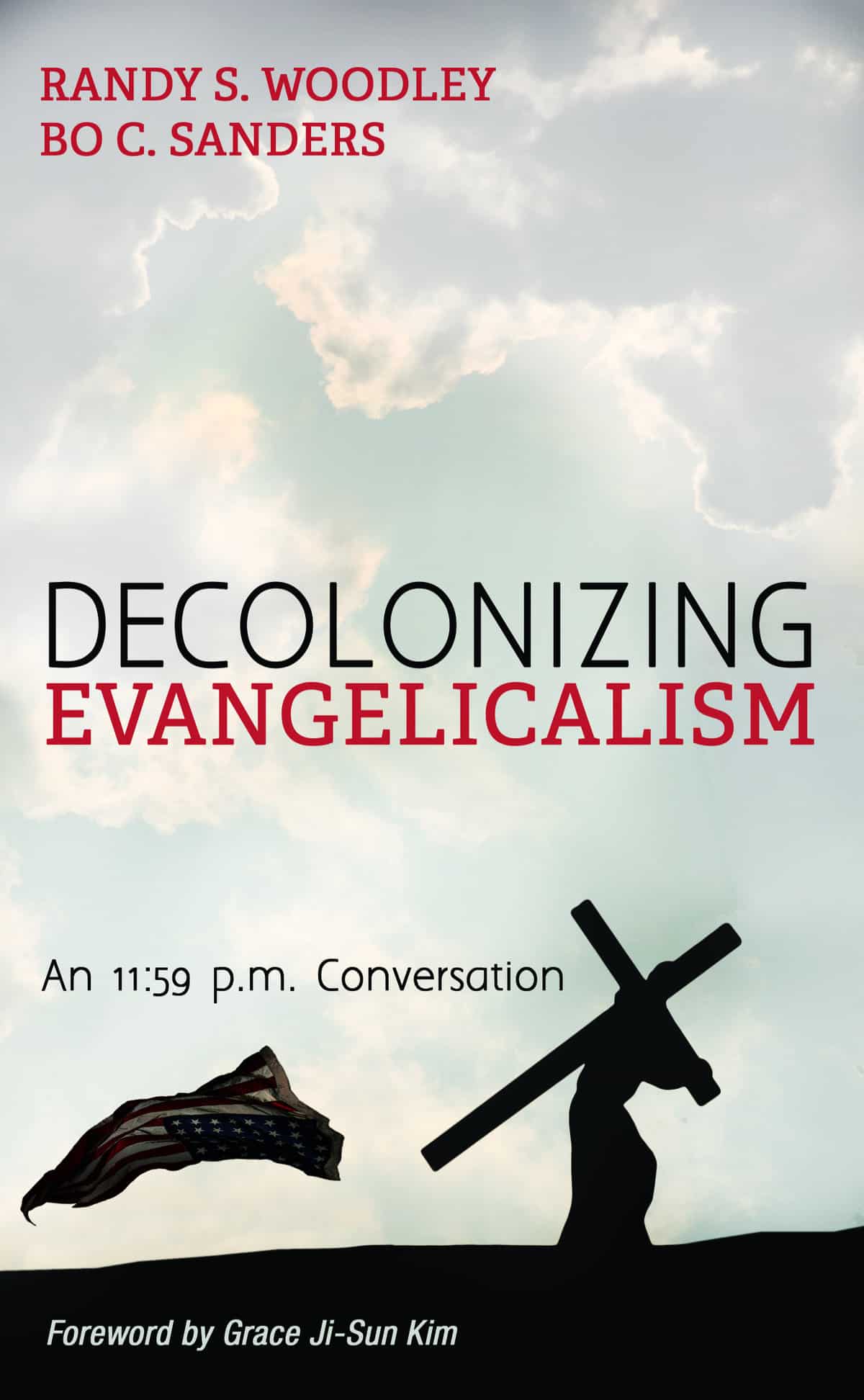

A Review of Decolonizing Evangelicalism by Randy S. Woodley and Bo C. Sanders

Shortly before he passed on, my friend, Diné (Navajo) scholar Larry Emerson, said to me, “You should write about decolonizing Christianity. Use that word, ‘decolonizing.’ It’s a powerful concept.” I felt honored that he would make the request, and I wanted to honor his memory. I also felt inadequate to the task. As a queer white woman, raised by evangelical missionaries in Navajo Country, I’ve had my own struggles with how colonization has compromised Jesus’ message. I grappled with Larry’s “commission” for a few years before finally coming to the realization that there are many ways to engage this vital topic, one being to elevate what others are writing on decolonizing Christianity. This review is my first attempt at just that.

In Decolonizing Evangelicalism: An 11:59 p.m. Conversation, Randy Woodley (Keetoowah Cherokee) writes that postcolonial theology should be written “from and for those who have been most negatively affected” by colonization. This is exactly why I felt I must write about what people like Woodley were saying, not what I might say. On the other hand, in the Americas, we are all affected by colonization, whether we descend from the colonizers or the colonized, and not least those of us who profess to follow Jesus. As Desmond and Mpho Tutu say in The Book of Forgiveness, “To walk the path of forgiveness is to recognize that your crimes harm you as they harm me. To walk the path of forgiveness is to recognize that my dignity is bound up in your dignity, and every wrongdoing hurts us all.”

Decolonizing Evangelicalism is written as a lively dialog between two friends who share a long history as leaders in evangelical faith communities: Woodley and Bo Sanders, a non-Native. Central to Woodley’s vision of decolonized Christianity is Jesus’ kingdom of shalom, which he calls the “Harmony Way.” Living in the Harmony Way means extending hospitality, doing away with cherished doctrines that perpetuate a culture of “who’s in and who’s out.” Thus, the authors point out that decolonizing Christianity necessitates learning from theologies of all marginalized people—Indigenous, African American, Latinx, queer, disabled, and female, and others.

We in North America who aspire to shalom, the Harmony Way, are obligated to participate in reversing the effects of the European invasion and its philosophical foundation, the Enlightenment, which is based in the mind—thinking rather than doing. By contrast, shalom is something that must be done. Jesus’ shalom and the Indigenous Harmony Way require cooperation above competition, community over the individual, reciprocity with the land and all of creation, and diversity over uniformity. Shalom is about love, and Woodley suggests that “love can be the essence of postcolonial mission. The first step of shalom is vulnerability in welcoming people, especially those different from us, through hospitality.” There is no us vs. them, no more “who’s in and who’s out” in God’s kingdom of shalom.

Colonization has shown itself on the mission field in a failure to recognize that Indigenous people already had a viable theology before the missionaries came–by and large a creation theology. Woodley points out that indigenes did what Jesus did: they observed and learned from creation, surely a praxis we can all learn from. Woodley goes on to amply demonstrate support for creation theology and its path to knowing God through scripture. The Good News is not bound by our human cultures; in fact, Jesus called Jews to follow him as Jews, Gentiles to follow him as Gentiles. I once heard a Diné Christian say, “I wonder what Christianity would look like in Navajo Country today if the missionaries had brought us the Good News and then left.” In other words, how would the faith look if Westerners had not layered their colonizer culture on top of and indeed kneaded it into and through the gospel? I suspect that Native Christians would then have been free to walk the Jesus Way as themselves, as Jesus intended.

The choice to write Decolonizing Evangelicalism as a conversation is no accident. Its very structure invites Jesus followers into the same conversation with one another. Lists of penetrating questions are shared throughout the book to help us examine how our faith communities have participated, and participate still, in the legacy of colonialism. Questions about council decisions –“How did one get invited to the council?” and “Were there any voices not present?”—need to be asked when examining the history of our own denominations. Looking at colonialism, we may ask, “We know that there were victims–but when do we hear from the victims?” This book offers itself as a guide to churches, small groups, and faith partners longing to live into Jesus’ kingdom of shalom–needing to begin or continue with the hard but rewarding conversations, needing to be transformed.

Anna Redsand is the author of To Drink from the Silver Cup: From Faith through Exile and Beyond. Shorter published works engage with issues of identity, culture contact and conflict, and with the healing of the effects of colonization. These works and her blog can be found on her website, AnnaRedsand.com.