Over the past few months, many relatively-privileged people in the U.S. have experienced the terror and overwhelm of empire’s destructive violence in a highly personal way for the first time.

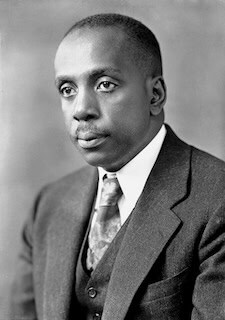

But others have been processing the horrors of living under the thumb of empire for a long time already. Those who have suffered under violent rule—and who have learned how to live meaningful human lives in its midst—speak into our present moment with wisdom and urgency. Black American theologian and pastor Howard Thurman (1899-1981) stands among them, and his thinking remains as relevant today as ever.

In his 1949 book Jesus and the Disinherited, Thurman explores the life and teachings of Jesus, arguing that for the Jewish people of Jesus’ day, the “urgent question was what must be the attitude toward Rome.”[1]

For Jesus’ audience, Thurman writes, “Rome symbolized total frustration; Rome was the great barrier to peace of mind. And Rome was everywhere.”[2] People of Jesus’ day wondered: “Was any attitude possible that would be morally tolerable and at the same time preserve a basic self-esteem—without which life could not possibly have any meaning?”[3]

These questions cut to the core of what we’re experiencing today.

We might find ourselves asking:

- How do we respond to empire’s oppressive actions in our time?

- How do we preserve our sense of self-value and self-worth under an administration that has no concern for it?

- How might we find inner peace—not a willfully ignorant, head-in-the-sand kind of peace, but one that acknowledges our violent reality and discerns how to live well within it?

As ever-tenuous social safety nets are cut from beneath our feet, as open proponents of white supremacist patriarchy consolidate power, as economic systems shudder and threaten to collapse, as the Department of Defense is renamed the Department of War—we might find our own sense of security fundamentally destabilized.

More and more of us might find ourselves, in different ways, among those “masses of [people]” who “live with their backs constantly against the wall”—that is, among “the poor, the disinherited, the dispossessed.”[4]

As our country’s and our world’s situation becomes increasingly dire, we might find ourselves encouraged by Thurman’s perspective that attending to our own inner state of being is an essential piece of resistance. “Anyone who permits another to determine the quality of his inner life,” Thurman reflects, “gives into the hands of the other the keys to his destiny.”[5]

For Thurman, “no external force, however great and overwhelming, can at long last destroy a people if it does not first win the victory of the spirit against them.”[6] No matter how powerful the oppressive forces that impact us may be, we can refuse to allow them this “victory of the spirit.”

Our current administration is surely waging the “perpetual war of nerves”[7] Thurman writes about. “There are few things more devastating,” he says, “than to have it burned into you that you do not count and that no provisions are made for the literal protection of your person…The underprivileged in any society are the victims of a perpetual war of nerves.”[8]

Acts of violence and threats of violence are constant and real. And the daily news that seems to get worse and worse all the time grates on our nervous systems. People in power intentionally throw so many changes at us at the same time that we cannot keep up with it all. Our nervous systems are overwhelmed.

In a time like this, Thurman suggests, grounding ourselves in our identity as God’s beloved children holds power. Finding a sense of security in God’s parental, personal, attentive love can cut through our despair[9] and can even make us fearless.[10] It “gives a note of integrity” to everything we do[11]—and it “tends to shift the basis of [our] relationship with all [our] fellows.”[12]

We learn to see one another as part of one human family, created with intention and held together by an infinitely loving Parent.

In light of this identity, we find ways to live with creativity and courage. We resist the impulse toward hatred—not because there aren’t good reasons for it, but because “hatred tends to dry up the springs of creative thought in the life of the hater.”[13]

We refuse to allow hatred to destroy us, or to cause us to “[do] to other human beings what [we] could not ordinarily do to them without losing [our] self-respect.”[14]

Now more than ever, we dig our heels deep into the “love-ethic” that, according to Thurman, was “central” to Jesus’ life and teachings.[15] We move toward “neighborliness” of a kind that crosses “barriers of class, race, and condition” to “[respond] directly to human need.”[16] We move beyond one-sided ways of ministering or giving and into “the simple practice of brotherhood in the commonplace relations of life.”[17]

Following the lead of many Indigenous thinkers, I would call this “kinship”: a way of seeing all people as equally deserving of the conditions that make human thriving possible. We see that we are all related to one another.

Thurman’s vision of shared humanity, non-retaliation, sincerity, integrity, kinship, and love speaks directly into our lives today. It makes a way for us to “live effectively in the chaos of the present.”[18]

For Thurman, “wherever [the spirit of Jesus] appears, the oppressed gather fresh courage; for he announced the good news that fear, hypocrisy, and hatred, the three hounds of hell that track the trail of the disinherited, need have no dominion over them.”[19]

For us today, this is good news indeed.

Endnotes

[1] Howard Thurman, Jesus and the Disinherited (Boston: Beacon Press, 1996), 12. Originally published by Abingdon Press, 1949.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., 3.

[5] Ibid., 18.

[6] Ibid., 11.

[7] Ibid., 29.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., 24-5.

[10] Ibid., 39.

[11] Ibid., 43.

[12] Ibid., 40.

[13] Ibid., 77.

[14] Ibid., 72.

[15] Ibid., 79.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid., 3.

[18] Ibid., 99.

[19] Ibid., 19.

Liz Cooledge Jenkins is a Seattle-based writer, preacher, former college campus minister, and the author of Nice Churchy Patriarchy: Reclaiming Women’s Humanity from Evangelicalism. She writes regularly at growingintokinship.

Liz Cooledge Jenkins is a Seattle-based writer, preacher, former college campus minister, and the author of Nice Churchy Patriarchy: Reclaiming Women’s Humanity from Evangelicalism. She writes regularly at growingintokinship.

One Response

I loved this piece, Liz. Thurman’s words are sadly just as relevant today as when they were first written.