Editor’s note: Originally published March 3, 2022, we believe Liz’s suggestions below, after completing a month-long celebration of Black authors, can be a meaningful way to both kick off Lent and to continue to honor and learn from our Black brothers and sisters.

Editor’s note: Originally published March 3, 2022, we believe Liz’s suggestions below, after completing a month-long celebration of Black authors, can be a meaningful way to both kick off Lent and to continue to honor and learn from our Black brothers and sisters.

A year or so ago, as Ash Wednesday 2021 approached, I considered whether there was anything I wanted to give up for Lent. Past years’ choices included chocolate, meat, and Facebook. (I’m not sure which was the most difficult of those three.)

As I thought about it last year, however, I thought about how much I had been reading. When I graduated from seminary in 2019, I was quite aware that the vast majority of my seminary-assigned readings were written by men. And so, after graduating, I had been intentionally seeking out female authors. Unfortunately—partly because I’m White and partly because many of my circles are White-dominated and partly because living in the U.S. means dealing with White Supremacy—“female authors” too often means, by default, “White female authors.”

I believed (and still do believe) that our theology, spirituality, and communities are severely warped if we’re only learning from White folks, just as surely as these things are severely warped if we’re only learning from men. But it didn’t necessarily come naturally to put this belief into practice.

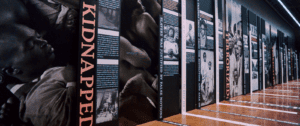

And so, for Lent 2021, I fasted from White authors. Not because all White authors are bad—just like Facebook isn’t necessarily bad, and chocolate definitely isn’t bad—but because they were vastly overrepresented in my reading. And that’s a problem. It’s a bigger problem than 40 days of fasting can solve. But Lent can be a place to start. (And when I speak of fasting from White authors, feel free to replace “authors” with “podcasters” or “preachers,” etc.—the point is to consider whom we’re listening to, learning from, and regarding as experts.)

We need this kind of practice—Lent or otherwise. Wealthy, White, Christian men—the ones who have disproportionately shaped the Western Christian tradition for so long—have gotten us into a complex mess of White supremacist hypercapitalist patriarchy. Sometimes our reflex is to turn to these same wealthy White Christian men to lead us out of this mess, to take us somewhere new. But often they are not able to.

We need different thought leadership. We need the wisdom and spiritual authority of those who have been on the underside of power structures and know the things that only those on the underside know.

We need to ask ourselves, as Ijeoma Oluo asks in Mediocre: The Dangerous Legacy of White Male America: “What does it look like to respect qualified women of color as thought leaders instead of waiting to turn to them in dire times as saviors? What does it look like to recognize that the ideas we have to help our communities might just benefit all communities? What does it look like to recognize that we are more than warriors, more than survivors—that we are innovators and leaders?”[1]

Authors of color, and especially female authors of color, are helping me think in new ways. They’re helping me become aware of the things I was (and am) missing. They are the people best equipped to lead us out of the things that have not served us well, and forward together into something new.

If Lent is a time of repentance, then fasting from White authors can help us repent from White Supremacy, from colonialist and imperialist ways of being. If Lent is a season of lament, then fasting from White authors can help us grieve our complicity in White supremacist ways of organizing our world. It can help us mourn the ways our theology and spirituality have been misshapen. It can help us lament the fullness of God that we have missed out on by only listening to some voices.

Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return, the Ash Wednesday liturgy goes. In Lent, we remember our mortality. We are reminded that we don’t have all the time in the world to figure out how to live. Given this reality, we urgently need to listen to the people who can best move us towards beloved community, justice, joy, and abundant flourishing for all people.

The season of Lent is short. But Lenten fasts can help us see more clearly how we want to live throughout the year. Fasting from White authors for a time can help us better seek out authors of color all the time.

For White folks, this is part of how we repent and turn away from the White Supremacist ways of being that have taken root in most of us. As we listen—really listen, dropping our defenses and being open to change—we may hear difficult things. That’s okay. It’s good, and it’s necessary.

I would also suggest, though, that we will not only hear hard things. For me, my efforts to learn from people of color have also been full of joy. Authors of color are doing so much amazing work that has resonated with me, challenged me, opened my mind, ministered to me, and made me angry about injustice in a way that makes me want to do something good with that anger.

I have missed out on so much when I have missed out on learning from them.

The White supremacist air we breathe has poisoned White people differently from people of color, but it has poisoned us all. Most of us are in desperate need of a detox. Consider a Lenten fast as one small step in the right direction.

[1] Ijeoma Oluo, Mediocre: The Dangerous Legacy of White Male America (Seal Press, 2020) 224.

Liz Cooledge Jenkins is a writer, preacher, chaplain, and former college campus minister who lives in Burien, WA. She has a BS in Symbolic Systems from Stanford University and an MDiv from Fuller Theological Seminary. She regularly posts justice-minded biblical reflections, poems, “super chill book reviews,” and more at lizcooledgejenkins.com; she can also be found on FB (Liz Cooledge Jenkins, Writer) and Instagram (@lizcoolj). Her sermon on Ruth and Boaz was included in Sojourners’ collection of immigration sermons, El Camino.

Liz Cooledge Jenkins is a writer, preacher, chaplain, and former college campus minister who lives in Burien, WA. She has a BS in Symbolic Systems from Stanford University and an MDiv from Fuller Theological Seminary. She regularly posts justice-minded biblical reflections, poems, “super chill book reviews,” and more at lizcooledgejenkins.com; she can also be found on FB (Liz Cooledge Jenkins, Writer) and Instagram (@lizcoolj). Her sermon on Ruth and Boaz was included in Sojourners’ collection of immigration sermons, El Camino.