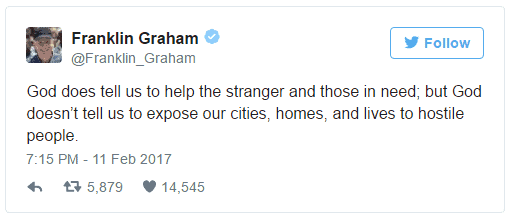

Last week I was lazily scrolling through my Facebook feed when I ran across yet another of Franklin Graham’s ignorant xenophobic statements. As a Latina evangelical it made me so angry I almost threw my phone across the room.

Then again, I saw the many responses of white evangelicals denouncing his xenophobia and appalling misunderstanding of the gospel.

They renewed my conviction to stay in the church and not abandon it because of its worst elements. I do not say this to limit the worst elements to people like Graham; there are plenty of unknown white evangelical pastors that are also ineffective and complacent.

But amidst these harmful voices are the 19% of white evangelicals who did not support Trump. Add to these the many evangelicals of color like me who also did not support him.

I work for an evangelical organization whose work in the U.S. is primarily in refugee resettlement and immigrant legal services. Most of my colleagues are white evangelicals, and after the election a bunch of us had an informal time of lament during our lunch hour.

I heard my white colleagues express their shame at the election of such a man by other evangelicals. They grieved for the state of the church and the vulnerable immigrants who would suffer under his vitriol and policies. The lament of these colleagues and friends was like water to my injured soul. As an immigrant myself, I saw the election of Trump as a very personal attack on my humanity. These colleagues give me hope, which is no small thing for a pessimist like me.

The lament of these colleagues and friends was like water to my injured soul. As an immigrant myself, I saw the election of Trump as a very personal attack on my humanity. These colleagues give me hope, which is no small thing for a pessimist like me.

The white evangelical church in the U.S. finds itself in a place of crisis where it needs the 19% for its renewal and, quite possibly, survival—if it wants to continue to be known as a church that follows the way of Jesus.

In my interactions with the 19%, I have seen white evangelicals who fight the racism and white supremacy found in the church, who take the side of vulnerable immigrants and refugees and protest xenophobia, and who want to see the patriarchy burned to the ground so that women are included at all levels of church ministry.

I recognize this is a small group of people within the evangelical church, but as Margaret Mead is believed to have said: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.”

One of the more difficult realities of life is losing a valued relationship. I have experienced this phenomenon on more than one occasion and know from experience that one of the losses is permission to speak into another person’s life. To put it simply: your voice no longer matters in the conversation because the relationship has been severed.

I believe the same is true of cutting ties with a church. It is true that I could leave the evangelical church and take my progressive convictions with me, but then the church loses my prophetic voice, which is necessary for its health.

I could leave the evangelical church and take my progressive convictions with me, but then the church loses my prophetic voice.

I say this not to overstate my importance, but the importance of all the progressive voices. However much prophetic voices are despised, unwelcome, and unheeded, they are needed and always have been.

Of course, there are costs to remaining. You may experience, as I have, the disappointment and sadness of watching yet another leader refuse to speak out against injustices or stand up for vulnerable people who are not fetuses. I do not want to minimize how painful it can be to stay.

But I am heartened by what Parker Palmer describes as the “tragic gap,” the place between the hard realities and the possibilities we know because we have seen them with our very own eyes.

Palmer describes our tendency toward either “corrosive cynicism” or “irrelevant idealism” as unwise and unhelpful. The place between them is the “tragic gap.”

Staying in the evangelical church means living in the “tragic gap,” for sure, and this is a place of ambiguity and uncertainty. But having seen the possibilities within the church, I also find it a place of great hope and joy as I get glimpses of what the evangelical church could be: a place of inclusion, love, truth, and mercy. I have caught some of these glimpses in big and small ways.

I have seen it in prominent evangelical writers who, at great professional cost, publicly affirm LGBTQI rights and call these relationships sacred. I have seen it in a church in my city that re-examined its exclusion of women from leadership, and though they lost hundreds of congregants, invited women to their pulpit.

And I have seen it over dinner, in a conversation with a friend where we speak the truth to each other graciously.

And truth be told, the “tragic gap” is the place I would have to live no matter what church I attend. All are imperfect, so I choose to remain in the church I believe needs me and those like me.

I was baptized in the Catholic Church and raised as a nominal Catholic, but I began to follow Christ in the evangelical church. I know there are faithful Christians in the Roman Catholic Church and in every denomination. But my journey of faith started in the evangelical church.

It was there that I learned language about God that I could understand and relate to. It was there that I learned that faith did not have to be formal and rehearsed—it could be spontaneous and conversational. It was there that I experienced God not just in words and in performing good deeds but in the experience of a vibrant relationship with a Creator who loves me.

It was there that I found community and acceptance after my mother died. It was there that I read and studied the Bible for the first time, and it came alive as a document that was written not to me but for me. And it was there that I first heard about God’s love of justice for the oppressed and marginalized.

…it was there that I first heard about God’s love of justice for the oppressed and marginalized.

I recognize that I learned things that were harmful, too. I am still kissing purity culture good-bye, and I am often ashamed and embarrassed at the lack of sound biblical scholarship that can easily be found in the evangelical church.

I am also still fighting the good fight for women’s inclusion in leadership, and for the church to support Black Lives Matter and LGBTQI rights. So I understand those who have chosen to leave, and I do not blame them.

But I am staying because it is the family I know and love. For me, the good within it is still worth fighting for.

Karen Gonzalez is is an immigrant from Guatemala, a writer, and an immigration advocate in in Baltimore, Maryland. She’s also the co-host of the Dovetail Podcast and can be found on Twitter musing about theology @_karenjgonzalez. This article first appeared on The Salt Collective.