I think every painter labors long, meticulous hours for those little encounters, brief as they may be, when their work surprises and disrupts the viewer. The piece of art suddenly seizes the viewer, who exclaims something like, “This image! I can’t explain. It’s doing something to my soul.” Sometimes their face is even filled with an expression of catharsis and relief. I know I’ve experienced it myself as a viewer. It is the sense that a piece of art, a film, a song, a story seems to read me while I interact with it.

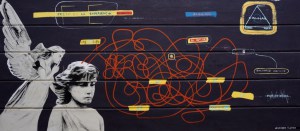

So I was a bit taken back when I showed a fellow artist my painting “In the Presence of My Enemies” (right), in its earlier stages, and she exclaimed, “Wow! I don’t like looking at this painting at all. It makes me feel deeply uncomfortable. It’s hard to look at it.” We were together at an artists’ retreat in Oxford, UK. Surprised and perplexed by her intensely visceral negative reaction, I urged her to elaborate. What provoked such a response?

She explained that a few years back she had been in a place of severe depression. The apparent loss of her faith and any semblance of mooring within her soul had left her feeling raw. She was vulnerable and terrified. She still wanted to believe. She simply could not muster the rational intellect to “just believe.” Showing up to church was excruciating for her. It was all she could do to attend services despite feeling empty inside. Yet, she continued to show up.

The grimace on her face while recounting this revealed what a dismal time it had been for her. She shared the one thing that carried her along in this period of loss: the Eucharist. This ancient tradition didn’t feel like something she needed to wrap her head around intellectually. She was free to simply embody faith independent of her mind’s full cognition. All she needed was to show up, receive and partake. She knew beyond the haunting shadows of her doubt that if mere intellect abandoned her, a beautiful, embodied liturgy of sacred ingestion could tether her fearful and frail soul to the truth of our Lord’s physical grace. Her faith was in his faithfulness.

My painting had re-enlivened those forgotten fears. She said with a low terror in her voice, “I hate the thought that someone could choose not to receive the very thing that kept me alive. The Eucharist was hope for me. I feel sick to my stomach knowing that someone could feel unworthy to take advantage of grace—the very thing that frees them.” I hadn’t intended to depict something so disturbing to my fellow victims of shame. I merely sought to share my experience of feeling unwelcome at the Lord’s table.

I’m a gay man who loves Christ, and I desire to live life as a faithful disciple of his. Yet, the poisonous words and messages from his self-proclaimed gatekeepers that have accumulated in my heart and body have long caused me to shrink back. His grace has felt so often felt like a bait-and-switch to me. These “gatekeepers” have wielded his name as a weapon of threat, so why would I not uninvite myself from the table of his hospitality? How could I not question my right to be there?

Despite the reality that these “gatekeepers” no longer physically surround me, their remembered words can still paralyze me with anxiety and panic. These ghost voices sound like snippets of memory: the time an older Christian leader, pivotal in my life at that time, said that gay men’s voices were “unnatural, and potentially caused by demonic possession”; the time a fundamentalist friend matter-of-factly stated that “capital punishment should be enforced for homosexuals.” The collection of these statements pile up and haunt me. They’ve scurried their way through my psyche over the years and continued to whisper. You’re too depraved to be loved and treated with dignity. God’s judgment is upon you! Any suffering and sadness in your life is God punishing you…, You don’t belong here. They’ve ensured a constant sense of danger in my mind. And the real horror? I’ve agreed with them. I’ve hung my head, and I’ve pushed my chair out from the table. I’ve wished I was allowed to participate in the meal. I’ve wished that this table was a safe space for me. But I’ve wholeheartedly agreed with the ghosts from my past.

In the 23rd Psalm, the psalmist writes that the Lord has prepared for them a table that they may feast in the very face of their enemies. The very same enemies who have long tried to shame, oppress and scorn their worthiness must now watch as God honors them. The enemies do not get to feast; they do not get to be celebrated…they must only watch and witness their victim’s vindication and embrace by God.

I’ve wanted to partake in this honorary supper. I’ve wanted to ingest the body and the blood that heals through the power of the resurrection. I’ve wanted to dine upon the reality that Christ has conquered the oppressive regimes of power hungry leaders, doctrines of injustice, and even my own participation in the broken sin patterns of our world. I’ve wished to delight myself on the concrete truth that God is good, gentle and kind. I’ve wanted to sit at this table as if I’m supposed to be here, as if my name is intentionally written on the placeholder. I’ve wanted to simply be me, to “come as I am,” and know that I’m safe. I’ve wanted to trust in the goodness of Christ. And yet, because of shame, I’ve refrained from the very banquet that was set for my own celebration at God’s victory over my enemies.

My fellow artist in Oxford was right: It is a dreadful thing to sit on the precipice of honor and to choose shame instead. The ravages of shame, along with the love and grace shame withholds us from, must be grieved.

Perhaps grief is the first counter-measure against these violent voices. The feast is laid out. The grace is poured for me like wine. It waits for me and all who, like me, doubt our place at the table . What will it take for us to partake?

Joel Richard Briggs is a fine arts painter working predominantly in contemporary figurative representational oil painting. His work currently explores the intersection of traditional religious symbolism with the present-day embodied experiences of shame, faith and sexuality. His influences range from Byzantine iconography, contemplative Christian practices, Jewish history and mysticism, shame psychology, linguistics, and Romantic and Neo-Romantic art movements. He is passionate about creating safe spaces of hospitality for LGBTQ+ Christians. He has a diverse and growing group of queer and straight folks that he calls his chosen family in his home of San Diego, California. His work can be found on Instagram @joelbriggspaints.