John the Baptist spots his cousin off in the desert distance and beckons with excitement:

John the Baptist spots his cousin off in the desert distance and beckons with excitement:

“Look, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!” (John 1:29)

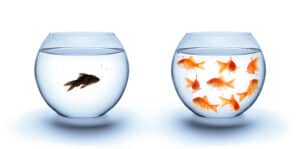

John’s words are worthy of our attention, because he articulates the future vocation of Jesus in a single sentence — a vocation that has been lost to many contemporary Christians, particularly those who reduce salvation to merely “personal” experience. Belief systems shaped by modern values like rugged individualism often lack the imagination needed to see the expansive hope Christ offers to creation.

When sin is reduced to personal transgressions alone, it only requires a personal salvation as its antidote. But this understanding fails to grasp the scale of Christ’s vocation — and with it, the scale of salvation itself.

Jesus comes to take away the sin of the world, John proclaims. World here literally means the cosmos. While individual transgressions are certainly included, the meaning is clearly wider. John’s contemporaries would have understood the cosmos to include malformed systems that curtailed collective liberation and wholeness.

Making this connection matters. In this sense, sin cannot be confined to individual wrongdoing; it also names the systemic inequalities embedded in lived oppression. As the scope of sin expands, so too does the scope of salvation. Christ’s work encompasses the righting of systemic wrongs that shape the lives of the many.

The malformed systems of sin at work in our world today are often described through overlapping forces such as capitalism, racism, ableism, colonialism, sexism, nationalism, and militarism.

When these systems work together against particular people and communities, they become the operating logic of empire. This is what John appears to be foretelling about the vocation of Jesus. Christ comes to counter the logic of empire with a new hope for wholeness.

Does this sound familiar? Hope amid hard times. Waiting with expectation for deliverance. These are precisely the themes of the Advent season.

Within the cultural context of Roman occupation and colonial expansion, hope for liberation was often imagined as material deliverance achieved through force. John seems to understand that Jesus will embody a different way. It is striking that John articulates Christ’s calling with such clarity, especially given how much difficulty the 12 disciples later had grasping it.

Yet this clarity should not surprise us. John carries forward a familial and prophetic legacy that begins with his aunt, Mary — the foundational prophetic voice of Advent, and one of the earliest voices of the Gospel itself.

Elizabeth, the mother of John the Baptist, and Mary, the mother of Jesus, anchor our expectations for deliverance. Mary’s song announces a hope rooted in resistance to the death-dealing ways of empire. In her Magnificat, we glimpse the renewed imagination Jesus will bring. She declares in Luke 1:50–53:

He shows mercy to everyone,

from one generation to the next,

who honors him as God.

He has shown strength with his arm;

he has scattered those with arrogant

thoughts and proud inclinations.

He has pulled the powerful

down from their thrones

and lifted up the lowly.

He has filled the hungry

with good things

and sent the rich away empty-handed.

Mary’s prophetic words are expansive and worthy of close attention. Mercy for all. The scattering of the proud. The lifting of the lowly. The filling of the hungry. These are the contours of the new logic Jesus ushers in — a stark contrast to the systems that distort human flourishing.

Here we find our hope for a renewed way of being: freedom from the forces that seek to make us less whole. This is Advent’s powerful invitation.

Advent is the prelude to God’s decisive intervention and declared solidarity with those on the margins. It holds out an expansive hope — one that includes material salvation and directly confronts the death-dealing ways of empire.

In an age where hopelessness feels abundant, this hope is especially poignant.

Advent calls us not only to wait, but to resist — to refuse the narratives of inevitability that empire relies upon. When we align ourselves with the vocation of Jesus, as first articulated by Mary, we embody postures that systems of domination ultimately fear.

Those possibilities emerge when people across difference align themselves toward collective liberation. Each act of resistance, each rejection of empire’s logic, participates in the unfolding hope that these forces will not have the final word. Our hope is not passive. It is practiced. And our full, material salvation awaits.

Rohadi Nagassar is the author of five books, including Whole & Human: Forty Meditations for Liberating Body and Spirit and When We Belong: Reclaiming Christianity on the Margins (2022). He serves as a part-time vocational minister and lives in Calgary, Alberta, on Treaty 7 land. Listen to his podcast, Faith in a Fresh Vibe (featuring the “Farewell Evangelicalism” series), or connect via rohadi.com and @rohadi.nagassar on Threads and Instagram.

Rohadi Nagassar is the author of five books, including Whole & Human: Forty Meditations for Liberating Body and Spirit and When We Belong: Reclaiming Christianity on the Margins (2022). He serves as a part-time vocational minister and lives in Calgary, Alberta, on Treaty 7 land. Listen to his podcast, Faith in a Fresh Vibe (featuring the “Farewell Evangelicalism” series), or connect via rohadi.com and @rohadi.nagassar on Threads and Instagram.