Originally published June 19, 2018.

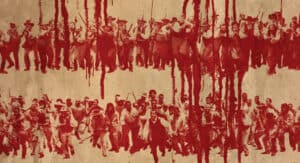

The statistics hang over the cities of America like a thick grey cloud, almost blotting out the light of hope and opportunity. One out of every nine young black males in the United States between the ages of twenty and thirty-four is behind bars. Today, more African American men are in prison than in college, an exact reversal of what it was twenty years ago. As a result of the failed “War on Drugs” and other get-tough-on-crime campaigns, the US now incarcerates more people than any country in the world.

Dr. Todd Clear, from the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York, has shown that these policy campaigns have compounded the problems they were intended to fix. In his masterful study, Imprisoning Communities: How Mass Incarceration Makes Disadvantaged Communities Worse, he has marshaled the evidence of a wide group of scholars in the fields of criminal justice and sociology to show that America’s current incarceration policies do more harm than good. That should alarm every pastor and spiritual leader in the country, to say nothing of those ministering on the front lines of our inner cities.

The Christian Community Development Association has developed an analysis for its members known as the CCDA White Paper on Mass Incarceration 2015. This assessment, intended to help urban ministry leaders think through issues related to criminal justice, highlights four major “drivers” that have fueled the explosive growth of prisons in America. They cite the War on Drugs, with its use of mandatory minimum sentences, the Private Prison Industrial Complex, the growth of Immigration Deportation Centers, and the School to Prison Pipeline. At the beginning of the war on drugs the fledgling DEA had less than 1,500 agents, but that number has now swelled to over 5,000 and the number of people in prison for drug offenses has increased by over fourteen hundred percent.

The use of mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines in drug cases has also forced judges to commit many non-violent drug users to lengthy sentences which have led to the dramatic expansion of prison populations. However, scholars have found that crime rates did not correspond to this dramatic increase in incarceration rates. There has also been an expanding use of incarceration for parole violations. In many cases, individuals have been returned to prison, not for a new crime, but for failing to keep an appointment with a parole officer, or missing a child-support payment, or even for losing a job.

All of these factors point to an increased population in our prisons, but the thing that brings the heaviest burden down on the backs of the poor is the way that bail is used in the whole process. Under historic usage, bail was intended to guarantee that an accused person would not flee jurisdiction, but would show up for trial. However, increasingly bail is being used, particularly in big cities, as a way to push the rate of convictions and “grease” the system to keep it moving. In the city prison where we serve in Philadelphia, approximately sixty percent of the inmates are awaiting trial. Many are too poor to pay for the unrealistic bail and so they sit in jail, whether innocent or guilty, for long periods of time while their cases languish for lack of good counsel. Many are then tempted to agree to a plea bargain, even if innocent, in order to gain release from the trauma of living in a crowded city jail. In a major expose article in the New York Times Magazine, Nick Pinto says, “as bail has evolved in America, it has become less and less a tool for keeping people out of jail, and more and more a trap door for those who cannot afford to pay it.”

In the city prison where we serve in Philadelphia, approximately sixty percent of the inmates are awaiting trial. Many are too poor to pay for the unrealistic bail and so they sit in jail, whether innocent or guilty, for long periods of time while their cases languish for lack of good counsel.

Today, many pastors seem to be immobilized by the enormous scale of these problems that they witness. However, we all need to be reminded that, just as in the days of the biblical prophets, we are part of a community that God cares about—and as representatives of that beloved community we can speak and act prophetically. In his classic volume, The Prophetic Imagination, Walter Brueggemann has shown the clear connection between a strong sense of community identity and the powerful expression of prophetic witness. The overwhelming testimony of scripture speaks of God’s concern for the family of believers, the community of the saints, and, through them, his love mediated to the broader community in common grace. “Such a subcommunity is likely to be one in which there is an active practice of hope…”

That sounds a lot like the church.

In her powerful book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in an Age of Colorblindness, professor Michelle Alexander states, “…it has been changes in our laws—particularly the dramatic increases in the length of prison sentences—that have been responsible for the growth of our prison system, not increases in crime.” She says, “The term mass incarceration refers not only to the criminal justice system but also to the larger web of laws, rules, policies, and customs that control those labelled criminals both in and out of prison. Once released, former prisoners enter a hidden underworld of legalized discrimination and permanent social exclusion. They are members of America’s new underclass.”

A Gospel response to such an unjust system of disparity requires not only coming alongside individuals in harm’s way and helping them to recover, but also prophetically facing the entire system and calling for a fundamental change in how we treat offenders and the restoration of our communities. That is exactly what we and our colleagues have done through Kingdom Care Reentry Network (KCRN) and its fabric of partnerships in the city. One church-based program could not do all that is needed, but by working together a variety of essential services can be provided to returning citizens. Through referrals within this new network of over sixty partners drawn from churches, faith-based community service organizations, and criminal justice agencies, KCRN has been able to provide a range of holistic supports.

A Gospel response to such an unjust system of disparity requires not only coming alongside individuals in harm’s way and helping them to recover, but prophetically facing the entire system and calling for a fundamental change in how we treat offenders and the restoration of our communities.

The most widely-recognized event associated with KCRN has been its sponsoring partnership of a U.S. Marshall’s program known as Fugitive Safe Surrender. The program was born in Cleveland, Ohio, when U.S. Marshall Peter Elliott dreamed of the possibility that the church might be a safe place for fugitives to surrender themselves. In the summer of 2007, we read a New York Times article about Pete Elliott and Fugitive Safe Surrender and sensed it might fit a need in Philadelphia. We invited some key leaders in our criminal justice system to a breakfast meeting to introduce them to the program and to discuss the prospects of bringing the program to Philadelphia at Bishop McNear’s church, True Gospel Tabernacle, Church of God in Christ, International.

The entire First Judicial District of Pennsylvania had to be mobilized. The city’s courts and its administrators, the district attorney’s office and its army of prosecutors, the hundreds of public defenders, and even the security officers and clerks joined this effort. The court records office with its thousands of files had to be plugged in to the church. Metal detectors had to be set in at every entrance to ensure a secure environment for the four courtrooms. Police had to seal off streets as well as provide armed security throughout the church. The U.S. Marshals brought in experts from their national office to coordinate the effort.

In a parallel process of recruitment and training of volunteers, we at KCRN embarked on a major effort with many of our ministry partners to have people ready to help, counsel, and direct these newly liberated folks toward needed help. Greg Thompson, KCRN’s program manager, trained and coordinated many service volunteers. The Department of Behavioral Health was there with professional staff. Philadelphia FIGHT, the region’s largest HIV/AIDS agency, was there with its doctors and outreach workers. Philadelphia’s Praise 101 Gospel radio station was also there with disc jockeys putting a sound of heaven over the whole scene. Many men and women came out of the church rejoicing and praising God that a burden which they had carried so long in secret was now lifted. In all, 1,248 people came through and had their cases processed by a judge. The unsolicited testimonial of a senior officer in the city’s Adult Probation and Parole Department, who wrote a reflective letter to Bishop McNear, impacted all of us deeply:

Dear Reverend Doctor McNear,

I am a senior administrator at the Adult Probation Department…I have worked here for 34 years and have seen a lot. I did go to your church last Friday morning to see what it was about. I was moved to tears. I was aghast at what I saw. The system set up there was a highly functioning microcosm of the entire criminal justice system. I worked that day until closing, interviewing and representing our department in court, things I have not done for decades. This was the practice of our profession in its highest form. It was humbling to see offenders cry with joy because they could walk out of your church without the millstone tied around their neck. Though I’m sure you would eschew such sentiments, this is a great thing you have done. It required no small amount of perseverance, but is its own reward. Those who proselytize about the separation of church and state should have been there too.

What have we learned from such a public / private collaboration? We have discovered a profound truth about the nature of biblical ministry and the complex systems required to govern a modern city. We have learned that by stepping outside the church into the moving stream of human needs that surrounds us, even a small to mid-sized church can impact an entire city as a testimony of their love for Jesus Christ and their willingness to serve the least, the last, and the lost. In a major article in the Philadelphia Inquirer, Bishop McNear said, “What we’re doing is living the Gospel, not teaching it. From my point of view, I think this is the perfect demonstration of law and grace.”

In terms of mass incarceration, we have been learning that there are many people who do not need to be in prison. Our court system and city jails are clogged with thousands of folks who have been retained on very minor offenses. Often, without sufficient means to post bail, many of these truly poor folks languish behind the walls while their cases drag through the system. At least for the thousand or so who showed up at True Gospel Tabernacle, one church was able to make a small, but significant, dent in a big problem.

However deep our country may be in a crisis that seems insurmountable, each church, small, mid-sized, or large, can do something. If every church that preaches the old-fashioned Gospel story on Sunday morning, would do something for these men and women on Monday morning, together we would make an enormous impact on this huge made-in-the-USA criminal justice problem. We believe that America has reached a tipping point in terms of mass incarceration. It’s time to turn it around.

One Response

I think this article will serve as a catalyst for Christians to show effective LOVE to the unreach in our communities who need to be shown the PURE love of God. The world need it.