Originally published October 4, 2020

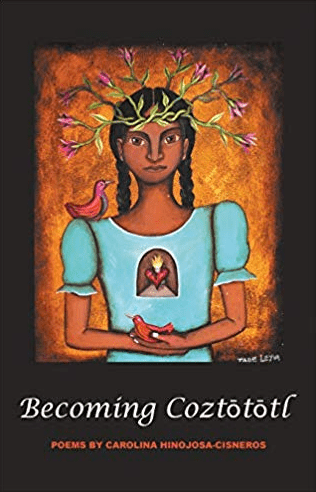

My first encounter with Tejana writer Carolina Hinojosa-Cisneros was through her Twitter account, where she asks thoughtful questions and offers kindness in her comments to poets, Christian writers, and anyone else who engages with her. Since our initial connection online, we’ve met at conferences and readings, and our work has shared pages in the same anthology. Though I am familiar with her prose, Becoming Coztōtōtl was my first time fully engaging with her poetry. “My life and passion are in poetry,” Hinojosa-Cisneros says. So it’s no wonder that she chose poetry for her book debut.

In Becoming Coztōtōtl, Hinojosa-Cisneros explores ancestry, spirituality, family, domesticity, immigration, and the body with open hands, taking the word “becoming” in her title seriously. Her use of Spanglish throughout the collection shows her familiarity with in-betweenness, but the tension there does not consume her. Indeed, Hinojosa-Cisneros embraces it. In the poem “In Lak’ech” (one of the meanings for this Mayan phrase is “I am you and you are me”) the speaker addresses her daughter, “Mi’ja, you are/of madre tierra. You are/trenzas por la madrugada.” Neither Spanish nor Nahuatl are translated into English.

In “Becoming Coztōtōtl,” Hinojosa-Cisneros explores ancestry, spirituality, family, domesticity, immigration, and the body with open hands.

In her poem “Fiesta,” Hinojosa-Cisneros shows she shares a common frustration with how Cinco de Mayo is celebrated on the U.S. side of the border. The only Spanish words she uses are “papel picado,” the name for the holey, colorful papers that hang during Mexican festivities. Her otherwise use of almost exclusive English shows that she wants to make sure every English-speaking reader understands. Nothing is lost in translation. She ends the poem:

The onlooker convinced

I am a beautiful piece of décor

to adorn the walls

on Cinco de Mayo.

As a Tejana, she is from a place better acquainted with the border, even if her own family’s crossing happened generations before her. While many of her poems explore a very personal, very intimate connection with her ancestors, her daughters, and the land, she explores a more universal outlook in others. In her poem “Decolonial Cartography of the United States of America,” she imagines new Americas “where the/north is not/pregnant/with empire.” In “Blessed Be the Mother,” she speaks of a woman crossing the border and being separated from her “hijitas and hijitos,” and includes the refrain from a well-known song written by Mexican composer and singer Tomás Méndez. This refrain is repeated every few stanzas, like a lullaby, first to her children and then to herself when she’s alone. “Cucurrucucú paloma/Cucurrucucú no llores,” the mother sings (translated to “Coo-coo dove. Coo-coo don’t cry”).

Hinojosa-Cisneros is not coy about where she stands regarding family separation at the border. Towards the end of the poem she writes:

Blessed be

the mother who spreads her wings in resistance.

Blessed be

the mother who reclaims her land.

Blessed be

the mother who meets the devil nose to nose

until her hijitas and hijitos are returned to her.

Bendita sea la madre.

There is no doubt Hinojosa-Cisneros is aware of her surroundings—growing up by the border, running in circles with poets and Christian writers. She knows that many have claimed God is more on the side of law and order than on the side of the suffering. And she has written in response to this in her articles in various publications. In her prose, she’s done the hard work of questioning the powerful and of speaking against structural oppression. But in her poetry, it is as if she rises above it, perhaps like the coztōtōtl (the Nahuatl word for canary) she’s becoming. This rising above is what most impacted me as I read her poems.

The land is older than we think. Lines drawn by newcomers do not affect how plants grow, how rivers travel.

Sometimes moving through life in the last few years—the news cycle, this administration’s decisions, the response (or lack thereof) from the Church—can feel too heavy to sustain. But Hinojosa-Cisneros reminds me of what is so easy to forget: The land is older than we think. Lines drawn by newcomers do not affect how plants grow, how rivers travel. She does not acknowledge a capitalistic, nationalistic God. Instead, she blesses the immigrant, the traveler, the suffering with certainty, as if she’s well-acquainted with a more ancient, more loving God.

Aline Mello is an immigrant writer. She was born in Brazil, moved to Massachusetts with her family, and then to Georgia, where she grew up. She holds degrees in English Literature and Spanish Language from Oglethorpe University. Her prose and poetry have appeared in On She Goes, St. Sucia, Saint Katherine Review, and elsewhere. She currently lives in Atlanta, Georgia with her sister and two pups.

Aline Mello is an immigrant writer. She was born in Brazil, moved to Massachusetts with her family, and then to Georgia, where she grew up. She holds degrees in English Literature and Spanish Language from Oglethorpe University. Her prose and poetry have appeared in On She Goes, St. Sucia, Saint Katherine Review, and elsewhere. She currently lives in Atlanta, Georgia with her sister and two pups.