I’m a member of a special task group on racial reconciliation that consists of a dozen or so pastors from around the Twin Cities. We’ve been meeting periodically for the past year or so in order to strategize how to help the church of the Twin Cities as a whole move forward in racial reconciliation. The other day we were discussing what we thought was the main obstacle(s) to the church becoming a reconciled, diverse community—one that manifests the truth that Jesus died to “tear down the walls of hostility” between people groups. I shared with the group my conviction that the main obstacle to reconciliation in the church in America is that the majority of white people don’t “get it.” What’s worse, the majority of white people don’t know that they don’t “get it.” Worst of all, the majority of white people don’t really know that there’s anything to “get.”

Most white people I know sincerely believe they live in a country that is, for the most part, a land of equal opportunity that is mostly free of racism. Yes, we all see the occasional overt racism that erupts now and then in America, and most of us are genuinely revolted by this. But we tend to see these events, and the attitudes behind them, as rather atypical of America as a whole. And, yes, most of us white folks know at least a little bit of the shocking statistics of disparity in America (e.g. young black males are statistically more likely to end up in prison than to go to college). But given our operative assumptions about America, we whites often either refuse to believe these statistics or, more commonly, we find ways to explain them away.

I honestly don’t for a moment think this is because white people are generally racist. I believe most white folks genuinely despise racism, so far as they understand it, and sincerely believe they are anti-racist, so far as they understand it. It’s just that they don’t understand it very far. Our awareness is stunted because our life experience tends to blind us to racism as a subversive structural issue.

My own life serves as an example of this. I grew up with a very progressively minded father. He strongly supported the civil rights movement and was one of the pioneers who fought to include African Americans in the Tire Union in the 1950s. I watched my father wail when Martin Luther King Jr. was killed, and I heard him incessantly curse George Wallace and other “stupid *&*% damn southern racists” throughout my upbringing. My point is that my own upbringing positioned me to be, at least on a conscious level, as free of racism as I could be. But I now see that, despite all this, I still didn’t “get it.”

Evidence of how little I “got it” is that I was genuinely surprised (and discouraged) when the church I founded and pastor (Woodland Hills Church) continued to be an almost exclusively white church for the first 10 years of its existence, despite my continual preaching that racial reconciliation is one of the central reasons God became a human and died on the cross. I honestly thought that if you simply announced to the world that you believed in the equality of all people and that God wants the church to be multicultural, it would happen. But I was wrong. I didn’t get it. And the reason is because, while my heart was in the right place and while I had some head knowledge of race issues, my life experienced had barricaded me from the real issue—the systemic, structural dimension of racism.

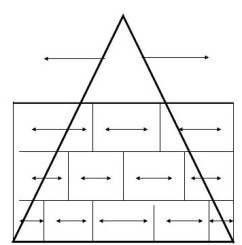

What I lacked, and what most white people lack, was a context where I was forced to notice something that almost all non-whites have to notice every day of their lives: namely, the reality of racist walls pervading the structure of our culture. As a white person, I didn’t have to deal with these walls. You see, for all our insistence that America is the land of equal opportunity, there is in fact a stratified “pecking order” of privilege that is largely structured by one’s access to power, social class, ethnicity, and even gender. We might think of it as a pyramid of privilege. The higher up the pyramid you are, the fewer walls you have to maneuver around. The lower down the pyramid you are, the more walls you have to maneuver around.

Here’s how I diagrammed it at the pastors meeting:

There are, of course, many variables that affect where one finds oneself on the pyramid—including how hard one works, how frugal you are, how talented you are, etc. This is why there are many exceptions to the observation that race is the primary determiner for where one falls on this socially stratified pyramid, and also why the exceptions are usually rather noteworthy (e.g. Michael Jordan, Oprah Winfrey, etc.). But all other things being equal, whites (and especially white males) enjoy the privilege of being at the top of the socioeconomic pyramid. This isn’t surprising, really, since America was founded (conquered) by Anglo-Europeans, and it has from the start been structured to their advantage. This is what is commonly known as white privilege.

There are, of course, many variables that affect where one finds oneself on the pyramid—including how hard one works, how frugal you are, how talented you are, etc. This is why there are many exceptions to the observation that race is the primary determiner for where one falls on this socially stratified pyramid, and also why the exceptions are usually rather noteworthy (e.g. Michael Jordan, Oprah Winfrey, etc.). But all other things being equal, whites (and especially white males) enjoy the privilege of being at the top of the socioeconomic pyramid. This isn’t surprising, really, since America was founded (conquered) by Anglo-Europeans, and it has from the start been structured to their advantage. This is what is commonly known as white privilege.

All of this means that, among other things, whites can move around freely and not bump into the walls that increasingly box people in the lower one goes down the pyramid. And this is why, all other things being equal, whites have trouble “getting it.” We simply aren’t aware of the walls. Indeed, many of us deny there’s even a pyramid that we’re at the top of. This is, after all, the land of equal opportunity. By virtue of the racialized structure we benefit from, we are, on a structural level, protected from the walls of racism. For all our sincere intentions, we are sheltered from a whole world of experience that non-whites, in varying degrees, are forced to live in. It is therefore hard, if not impossible, for many of us white folks to grasp with any depth the extent of (for example) racial profiling, red-lining, and job discrimination that non-whites experience. It’s simply not on our radar screen.

The radically different “worlds” of those who move freely at the top and those who confront walls toward the bottom were graphically illustrated during the O.J. Simpson trial. Close to 90% of African Americans thought O.J. should be acquitted. Close to that same percentage of whites thought he should be found guilty. It was an amazing moment in our history, uncovering the usually hidden chasm between the life experiences of whites and blacks.

During this trial I asked a close African American friend to explain to me how so many African Americans thought the case against O.J. Simpson was not sufficient to prove guilt. I was genuinely nonplussed. I didn’t “get it.” He proceeded to tell me about his experience as a black boy growing up in the Bronx. On three different occasions, he watched his father get beat up and humiliated by white police officers for no legitimate reason. “You can see why its not hard for me to believe that officer Mark Furman, a known racist, planted all that evidence against O.J.,” my friend told me. “And so it goes for a good many black folk.”

As a white guy, I’d never bumped into that wall. So the idea that a police officer would risk his entire career to bring down a famous black man seemed ludicrous. To black people who have had loved ones abused by police officers, or who have themselves been abused, the suggestion wasn’t ludicrous at all.

A coin dropped in the slot (or at least began to drop in the slot) that day. I began to “get it.” I’d had many non-white acquaintances before, but this was the first time I was close enough to hit a wall with someone. If white people are going to “get it,” I am convinced that this is how it is usually going to happen. Seminars and classes and books on racism are good and necessary. But in the end, I believe it’s going to come down to relationships. The racist system is structured so that we don’t notice the walls all around us—walls that are too invisible for most of us white folks to notice on our own. Not only that, but we benefit from not noticing the walls, for to notice them makes a demand on our life.

For us whites to really wake up to the reality of the thick, oppressive, demonic, but (to most of us white people) invisible walls that pervade our culture, we must develop peer relationship with non-whites who will call into question some of our most basic assumptions about American culture and perhaps about ourselves. This is not easy. It certainly doesn’t happen by cultivating cross-cultural relationships where non-whites are once again in a position of dependency on the whites. The relationships that whites need (if there’s any hope of them “getting it”) are relationships premised on equality, mutual trust, and respect.

It might seem artificial and odd—even perhaps quasi-racist—to seek out a friendship based primarily on race. Yet this is precisely what I would like to challenge all white people to do. Even if you are sure you already “get it.” If you have never significantly shared life with a non-white person, I strongly suspect you don’t. Even if your upbringing and education was uniquely anti-racist, as mine was, it’s far more probable than not that you’re blind to a racialized world that benefits you and oppresses others.

If the church is ever going to significantly manifest the beauty of God’s diverse humanity, it’s going to take place one life at a time. Reach out. Cross ethnic and culture lines. Watch how it challenges your paradigms, enriches your life, and expands your worldview.

At some point, you just might find that you truly begin to “get it.”

Greg Boyd is an internationally recognized theologian, preacher, teacher, apologist, and author. He has been featured in the New York Times and on The Charlie Rose Show, CNN, National Public Radio, the BBC, and numerous other television and radio venues. This article was republished with permission from ReKnew.