In evangelical culture, we sometimes learn to treat doubt and faith as opposites. We tell stories of how we used to doubt, but God rescued us and brought us to faith. Often, we think it is best to flee situations that challenge our faith and lead us into doubt.

But in my life doubt and uncertainty have become my best friends—and increasingly, rather than a hindrance, an encourager of my faith.

One evening, after I showed a film to half a dozen international students, my friend Haluk sat scrunched down on the couch. I was a bit embarrassed about the film myself.

“I wouldn’t have shown that one if I’d remembered some of those scenes,” I said to Haluk.

But Haluk didn’t care. To him, it was all just vocabulary practice.

“You’re a Christian, right?” he asked.

“Yep,” I replied, thinking how you might not have known that from the movie I’d picked to watch.

“So you read the Bible, right?” he continued.

“Yep. I love it.”

His next words caught me totally off guard. “I want to read it.”

I had told the truth. I love the Bible. I read it daily and listen to audio recordings of the Bible when I am at work. In the past six months I had easily listened to the whole Bible at least twice, and the Psalms more than that.

But I wasn’t used to other people saying that they wanted to read the Bible, not even most of my Christian friends. And here a Turkish Muslim was telling me that he wanted to read the Bible. How exciting!

“Sure,” I said, trying to act casual. I picked up a half dozen different translations from a chair. Carefully, I considered the merits of each. NASB was a great and very literal translation. Haluk is highly intelligent and might appreciate the faithfulness to the Hebrew and Greek idiom, I thought. But his English is shaky, so maybe not such a wooden and stilted version. I settled on an NIV as being best for an English learner. I held it out to him.

“Here, try this one. Let me know if you have any questions.”

Haluk looked at me as if I had misunderstood. “No, I want to read it with you.”

“It’s kind of long, you know,” I said. He was taking a very heavy load that year in college, and I had two jobs plus a family. When, I thought, would we have enough time together to read it?

But he was not to be dissuaded. In the end he convinced me to come to his apartment at 4am each day to read. Right, I thought, sure: you’ll be up at four!

But when I arrived the next morning Haluk had a large pot of coffee ready, and I brought in two copies of the same translation.

“I was up ’till 2AM working on a project for my Marketing Strategy class,” he chuckled. I knew Haluk well enough to know that he wasn’t complaining; he was bragging. He’d gotten less than two hours of sleep, but he was ready to read with me before his day of classes began.

And so we read. For the next few months we got up early and read together for three or four hours before I went to work and he got ready for school.

We read nearly everything. When we got to the “begats,” the long sections that list off the genealogy and who was the father of whom, I was tempted to skip them. How boring, I thought. But I couldn’t think of any way to explain to Haluk why we should skip them. After all, I had told him that I understood the Bible to be God’s Word. How could I now tell him that parts of it were God’s Boring Word and might as well be skipped? Far be it from me to admit to a sliver of doubt, and so I gritted my teeth as we plunged in and pushed through.

It all seemed different to me from before, knowing that the man reading beside me didn’t share my assumptions about the Bible.

What is he getting from all this? I wondered. It all seemed different to me from before, knowing that the man reading beside me didn’t share my assumptions about the Bible. How different did it seem to him? Often he would stop the reading and tell me that he recognized the name of a town that we were reading about. He’d tell me of an uncle whom he had visited near there, and how he hadn’t known at the time that it was in the Bible. Or we’d see some obscure name that seemed to me not even worth remembering and he’d say, “We still use that name. Not in Turkey, but in Syria where my family originally came from.” His memory of places and of names amazed me.

And then, more than a month into this adventure in sleep deprivation, we finally came into the beautiful Psalms. I was so relieved that Haluk had not yet gotten bored and quit.

One day we came to Psalm 42. I skipped the intro to the Psalm as being unimportant, and launched into the beautiful poem. I could recite it in the King James, but I read it so that it would match the copy of the NIV we each had in front of us.

“As the deer pants for streams of water, so my soul pants for you, my God,” I read.

“Wait,” Haluk interrupted. “You skipped part. It says this is a maskil of the Sons of Korah.”

I looked up. “Yup.” So what? I thought.

“Which Korah,” he asked. “The one that God killed in the desert? Or the one who is Esau’s son?”

Of course I had no idea. I didn’t know, because I hadn’t cared. I was worn out from all of these early mornings, and I was ready for the breakfast that we would make after reading and before we went our separate ways for the day. But again, I set my jaw straight, and we looked up the two Korahs. He was right. They were different. And since God had killed one of them, along with his children, it seemed likely that this referred to the other Korah.

But that didn’t make much sense to me. The other Korah was a son of Esau, who was a grandson of Abraham. But in my understanding, Esau dropped in importance as soon as he sold his birthright to his brother Jacob.

Their father’s blessing rested on Jacob (also called Israel), according to Genesis. I thought that God had forgotten about Esau’s family after that point as much as I had. From Jacob’s line came all of the Israelites; only with this line I saw God at work in the world.

But why then were Esau’s descendants writing God’s Word? And why, as we sat there staring at it, did God’s Word list Esau’s sons and grandsons and his lineage for many generations? And why, as my eyes scanned the page in 1 Chronicles, did the Bible also list the genealogy of Ishmael? He had been kicked out of Abraham’s home along with his mother, according to my memory of Genesis.

The fact is that I had long ago absorbed the idea that God had singled out the Jewish people for himself as his special nation. Through them the Messiah would come. To them God made covenants; to them God gave the law on Sinai; through their prophets God had given his word to the world.

And with this I had also accepted an altogether untested and unchallenged idea: that when God chose Israel he automatically chose to ignore everyone else. I knew of only one way for non-Israelites to learn truth about Yahweh; they could be taught by descendants of Israel; they could become Israelites. Surely other nations had no knowledge of the true God? Esau had lost the blessing; he must also have lost contact with God.

I had accepted an altogether untested and unchallenged idea: that when God chose Israel he automatically chose to ignore everyone else.

But as I sat there beside Haluk, I asked for the first time: Did God really ignore the rest of the world when he chose Israel? Why then am I staring at the genealogy of Esau and of Ishmael? Why did recording their lineages matter to God enough to be recorded for all time in God’s Word? Was it possible that some of their descendants became the authors of some of the Psalms? Was God working even then in nations other than just Israel?

These questions seemed crazy to me at the time. I felt guilty even asking them. I doubted my understanding of Scripture, and that doubt felt like a weakening of faith. My church stressed that we were saved by “faith alone.” For me there could be no more frightening position than to feel that my faith was weakening. That was the cord that bound me to Christ.

But after asking these questions now for many years, I am convinced that the answer is that God indeed remained actively at work among many peoples, maybe all peoples. Scripture has convinced me of this. Paul explains it in his Mars Hill discourse when he says:

From one man he made all the nations, that they should inhabit the whole earth; and he marked out their appointed times in history and the boundaries of their lands. God did this so that they would seek him and perhaps reach out for him and find him, though he is not far from any one of us. ‘For in him we live and move and have our being.’ As some of your own poets have said, ‘We are his offspring.’ (Acts 17:26-28)

Not only does Paul insist that God remained active and near to those in all other nations, but he goes even further. He quotes two of their own poets as having written rightly about the same God whom he was now proclaiming to them. Before Jesus’ time, Paul says, Epimenides and Aratus had each spoken correctly about God.

My childish notion that God’s choosing Israel required his rejecting every other people is just that. It is childish and requires that we set aside the abundant testimony of both the Old and New Testaments. Once the question was raised to prominence in my mind, I began to see contrary evidence everywhere.

My childish notion that God’s choosing Israel required his rejecting every other people requires that we set aside the abundant testimony of both the Old and New Testaments.

Because I questioned, God has been massively magnified in my eyes. My vision was too small; through doubt God stretched my mind to see more of his heart.

It is too small a thing for you to be my servant to restore the tribes of Jacob and bring back those of Israel I have kept. I will also make you a light for the Gentiles, that my salvation may reach to the ends of the earth. (Isaiah 49:6)

I am profoundly grateful to Haluk for planting that first doubt in my mind. Through simply opening the Bible with someone who didn’t share my assumptions about it, I have been blessed to see a more holy and patient, more gracious and beautiful vision of our Creator and Lord.

In the years since reading with Haluk I have opened the Bible with many Muslim friends. Without exception, I can say that every time I have come away with increased love for the book and greater awe and joy in the God I find in it.

May we all learn to seek out opportunities to have our assumptions challenged by those who don’t share them. But we won’t grow from discounting the doubt that may come from such encounters. Welcome the doubt. Some may tell us that doubting our assumptions is the same as doubting God. It is not. Doubt and faith are natural friends.

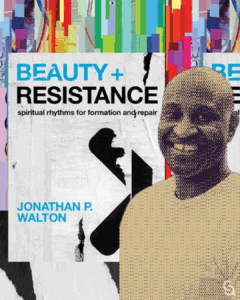

The father of four daughters, Doug Baker is the author of Covenant and Community and is passionate about increasing the connections between Christian and Muslim communities.

2 Responses

Wow! Wow! Really, wow! What a poignant expression of your journey in faith seen through your commitment (4 a.m.? Ahem!) to sharing your faith. You’ve opened my eyes too. First to ways that doubt (I understand you to mean uncertainty and incomplete knowledge) and faith can coexist and buttress one another. But also to that unremembered, unexpected fact, that Esau and Ishmael’s genealogies are listed in the Bible. Thank you for sharing! I will post this article to Twitter.