Rethinking the mission paradigm in favor of bearing witness to the Gospel

The question of responsible Christian political engagement is one that has occupied my life and work over the last three decades. I guess this was inevitable, as I served in various leadership roles in international and national organizations, focusing attention on the work of the Gospel in Africa, more broadly, and in Uganda more specifically. Several dimensions of what Christian political engagement means have troubled me, one of which is why Christianity seems incapable of disrupting political narratives of injustice, oppression, exclusion, plunder and gross inequalities in society.

Africa has been the theater of conquest, extraction, violence and dysfunctional states since the colonial era. This is the same Africa that is commended as a great success of the modern missionary movement and is now characterised as a new center of World Christianity[1] and home to “potentially the representative Christianity of the 21st century.”[2] It should trouble us that “despite the growth of Christianity and the social activism of the churches, Africans are in general 40 percent worse off than they were in the 1980s.”[3] I share Emmanuel Katongole’s angst when he asks why Christianity, in recent history, “despite its overwhelming presence, [has] failed to make a significant dent in the social history of the continent.”[4] My experience of Uganda during my lifetime gives credence to this angst: I have witnessed 50 years of fear, violence, death and trauma, in a turbulent Uganda, with militarism defining the management of the Ugandan state—and this in a country reputed to be one of the success stories of Christian mission, where over 80 percent of the population claims to be Christians today.[5] How can it be that Christianity, which heralds the gospel of love and justice, is also part of the story of violence and an attack on human dignity?

Sadly, modern and contemporary history is rife with similar stories and experiences around the world. The United States of America, though portrayed as a country founded on Christian values of life and liberty, bolstered by the myth of the Pilgrim and Founding Fathers, was in fact founded on war, bloodshed and wanton plunder of the native nations.[6] The Canadian myth of peaceful colonization has likewise been exposed as the systematic genocide of the native populations.[7] The post-Reformation so-called “Christian” wars— between Catholics and Protestants in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, during which they killed each other by the hundreds—is well documented—as is apartheid in South Africa, a system of racial segregation and white minority rule that was built, justified and sustained by Christianity for decades. Countless such stories abound.

Writing in the 1940s, African-American author, philosopher, theologian, educator, and civil rights leader Howard Thurman, a grandson of slaves, put the question well:

Why is it that Christianity seems impotent to deal radically, and therefore effectively, with the issues of discrimination and injustice on the basis of race, religion and national origin? Is this impotency due to a betrayal of the genius of the religion, or is it due to a basic weakness in the religion itself? The question is searching, for the dramatic demonstration of the impotency of Christianity in dealing with the issue is underscored by its apparent inability to cope with it within its own fellowship.[8]

In other words, is the absence of responsible Christian political engagement a betrayal of the gospel? Or is it what the gospel teaches?

The Lausanne Covenant affirms that “the Gospel is God’s good news for the whole world”[9] and thus suggests that the problem does not lie in the nature of the gospel itself. In fact, the same Covenant is clear that those who “believe the Gospel is God’s good news for the whole world” and “are determined by his grace to obey Christ’s commission to proclaim it to all [hu]mankind and make disciples of every nation”[10] ought to share in God’s “concern for justice and reconciliation throughout human society and for the liberation of [humanity] from every kind of oppression.”[11] I submit that the impotency of Christianity lies in a betrayal of the mandate “to proclaim” the gospel, by misnaming our place in the world in terms of mission rather that bearing witness. I am suggesting that the “Great Commission” as a paradigm for understanding the gospel and its mandate distorts the gospel and misplaces the believer and believing community in the world. I concur with Christopher J. H. Wright, who identifies this important fault line in the mission paradigm:

In missionary circles the Great Commission is frequently surrounded with military metaphors … This text is said to provide the church’s marching orders, for example, not to mention the whole range of other military metaphors that follow—warfare, mobilization, recruits, strategies, targets, campaigns, crusades, frontlines, strongholds, the missionary “force” (i.e. personnel) and the like. The language of authority seems easily converted into the language of mission, with the military metaphor functioning as the dynamic connector.[12]

It is not surprising then, that “mission” has disabled responsible political engagement by being oriented towards conquest and domination. Moreover, as those schooled in the original languages of the Scriptures have pointed out, the correct translation of Matthew 28:20 does not place the imperative on go, but rather on make disciples (“going” could be read “as you go”).[13] Therefore, “all the emphasis on the word go in much mission rhetoric is undermined by the recognition that it is not an imperative at all in the text, but a participle of attendant circumstances…”[14] The paradigm which is consistent with accounts of the four gospel writers is testimony or bearing witness.

The work of believers and believing community in society is not to impose either the Gospel or its vision of a society shaped by that story, but rather to discern the signs of God’s work (within and without), to bear witness and to commend it—to “let your light shine before others, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your Father in heaven” (Matt. 5:16). In bearing witness, the believer and the believing community become the visible presence of love, peace and justice in the political arena, because the One who is the light of the world shines through them. In engaging with systems and structures of power in society, they testify to the vision of the flourishing of all life and creation in God (eternal life), “on earth as it is in heaven” (Matt. 6:10). They live the story, as Jesus embodied God’s good news (incarnate); it is their pursuit. Additionally, in pursuit of the flourishing of all of life and creation, the believer and community in Christ confront and are confronted by the powers in the world that negate and oppose God’s reign of love and justice.

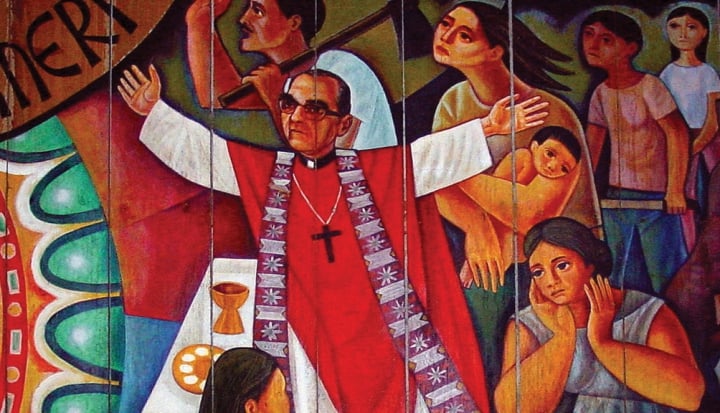

David Zac Niringiye (Ph D.) is an Anglican bishop from Uganda and a Senior Fellow in a nascent think tank, The Institute of Religion, Faith and Culture in Public Life (INTERFACE). Bishop Niringiye’s passion for the Gospel and his burden for justice brought an early retirement, in 2012, from serving as Assistant Bishop to serving the cause of social justice and good governance in Uganda. He now speaks internationally on the Gospel imperative for social justice in a broken and estranged world.

He has previously served at Makerere University, as a Visiting Fellow in the Human Rights and Peace Centre (HURIPEC) Department, in the School of Law, where he was leading a project on Religion, Human Rights and Peace. Prior to this, he served as Assistant Bishop for Kampala Diocese in the Church of Uganda for 7 years. He also served as the Africa Regional Director of Church Mission Society (CMS) and Regional Secretary for the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students (IFES) in English and Portuguese-Speaking Countries in Africa.

Currently researching for and writing a book called The Gospel and the Common Good, Dr Niringiye has authored numerous articles and three other books: Uganda Today: Crisis and Hope for Re-birth (Niringiye Publications, 2017);The Church: God’s Pilgrim People (The Langham Global Library, 2014) and his doctoral research, The Church in the World: A Historical-Ecclesiological Study of the Church of Uganda with Particular Reference to Post-Independence Uganda, 1962-1992 (Langham Monographs, 2016).

[1] In Kwame Bediako, Jesus in Africa: The Christian Gospel in African History and Experience (Carlisle: Paternoster Press, 2000), later published as Jesus and the Gospel n Africa: History and Experience (Orbis Books, 2004); Lamin Sanneh, Whose Religion Is Christianity? The Gospel Beyond the West (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2003).

[2] Andrew Walls, The Cross-Cultural Process in Christian History (Orbis Books, 2002), 85.

[3] Paul Gifford, African Christianity: Its Public Role (Indiana University Press, 1998), 15.

[4] Emmanuel Katongole, The Sacrifice of Africa: A Political Theology for Africa (William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2011), 40.

[5] According to the Uganda National Population and Housing Census of 2014, Catholics and Church of Uganda followers constituted 71.2% of the population. Religious affiliation was as follows: Muslims 13.7%, Pentecostals 11.1%, Roman Catholics 39.3%, Church of Uganda 32.0% (of a population of 34.6 million).

[6] There are several texts on this story. Gary Clayton Anderson’s account in Ethnic Cleansing and the Indian: The Crime That Should Haunt America (University of Oklahoma Press, 2014), is comprehensive.

[7] See essays in Colonial Genocide in Indigenous North America, Andrew Woolford, Jeff Benvenuto, and Alexander Laban Hinton (eds.) (Duke University Press, 2014).

[8] Howard Thurman, Jesus and the Disinherited (Beacon Press, 1996), xix.

[9] J. D. Douglas (ed.), Let the Earth Hear His Voice: International Congress on World Evangelization, Lausanne Switzerland (World Wide Publications 1975), 3.

[10] Douglas, 3.

[11] Ibid, 4.

[12] Christopher J. H. Wright, The Mission of God: Unlocking the Bible’s Grand Narrative (InterVarsity Press, 2006), 52.

[13] Craig S. Keener, Matthew: The IVP New Testament Commentary Series (InterVarsity Press, 1997), 400.

[14] Wright, 34-5.