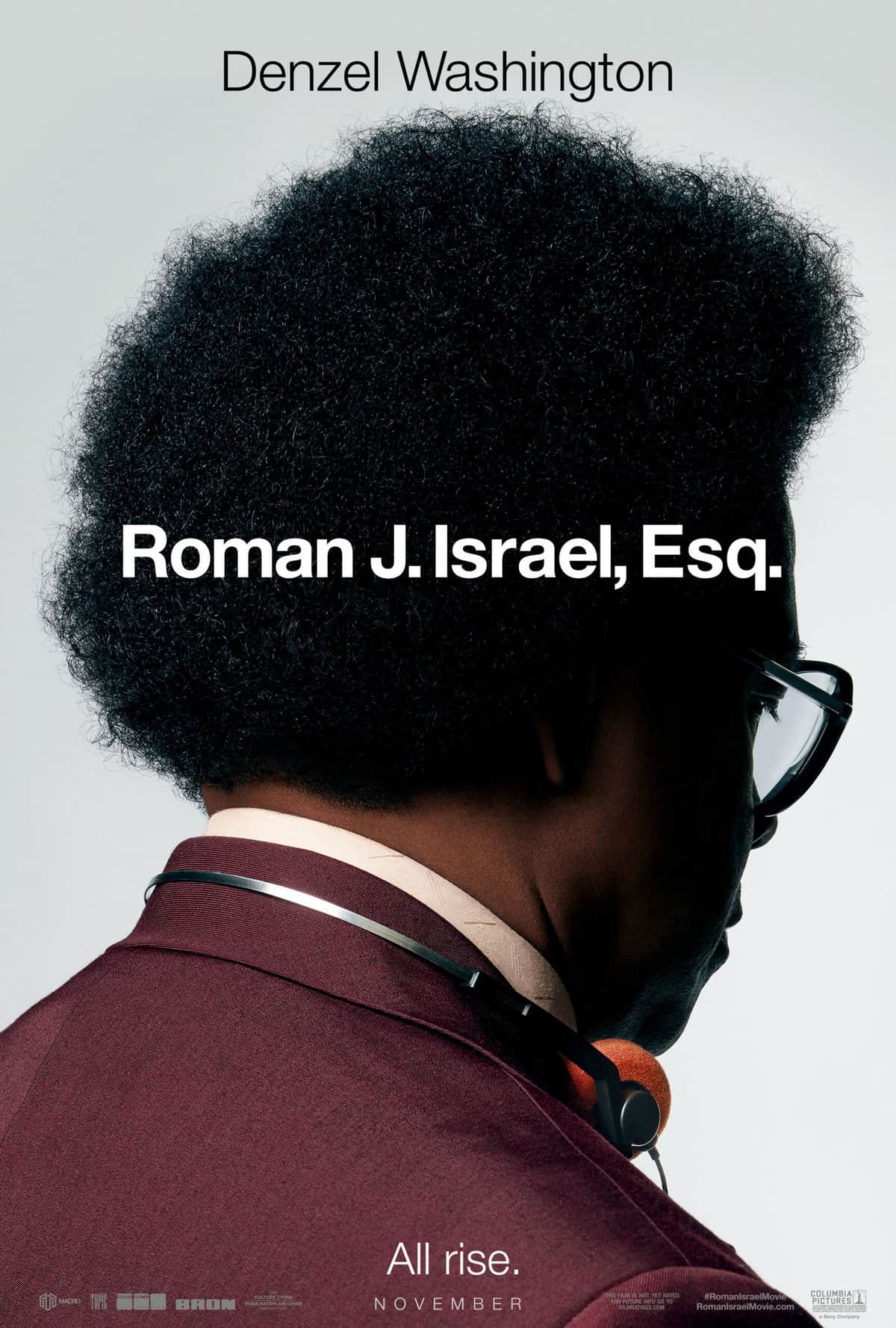

What we do behind the scenes often shows our truest intentions, especially when advocating for the marginalized. The film Roman J. Israel, Esq. (directed by Dan Gilroy, in theaters now) opens with its namesake writing a legal briefing in which both the plaintiff, and the defendant, are himself. Through examining his conscience in private, Roman reveals his intentions: He feels he’s made a grave mistake, but seeks absolution. What he truly seeks, splayed across the screen in large boldface letters, is Judgment.

What we do behind the scenes often shows our truest intentions, especially when advocating for the marginalized. The film Roman J. Israel, Esq. (directed by Dan Gilroy, in theaters now) opens with its namesake writing a legal briefing in which both the plaintiff, and the defendant, are himself. Through examining his conscience in private, Roman reveals his intentions: He feels he’s made a grave mistake, but seeks absolution. What he truly seeks, splayed across the screen in large boldface letters, is Judgment.

For what, exactly? His own actions? Oppressive systems? Complacency? The remainder of this uneven, yet periodically poignant film provides answers to some of these questions. Other answers are left to the viewer to decide.

With savant-like qualities, Roman J. Israel (in a magnetic performance by Denzel Washington) is a lawyer who prefers working in isolation. When his boss (and friend) suffers a heart attack, he is left under the tutelage of a well-intentioned but potentially misguided white lawyer named George Pierce (Colin Farrell, capping off a stellar year). As Roman settles into Pierce’s high-end law offices, he simultaneously connects with Maya Alston (radiantly played by Carmen Ejogo), a leader of the Los Angeles branch of a civil rights organization.

On the surface, Roman J. Israel, Esq. seems to cater to audiences like myself: young, justice-centered, progressive liberals. To my disappointment, however, the film seems to raise a number of good questions regarding justice, yet fails to provoke much thought or give further insight. At one point, the empathetic civil rights worker Maya asks, “Why do I care so much that our humanity is connected?” In response, Roman gives a speech heavy on his signature cocktail of riddles and legal jargon. This formula is applied to a number of situations, in which Roman responds to a thought-provoking question or anecdote with sentiments that would make more sense to someone who both loves solving riddles, and went to law school.

One instance where this is not the case, though, is a powerful scene in which Roman and Maya discover what seems to be a dead body on the street. After the police arrive, Roman attempts to place his business card with his personal number in the dead person’s pocket, against the officers’ direct instructions. Tension abounds as there is a nonverbal standoff between the two factions. Is it worth it, as Roman says, that the person doesn’t get cremated alone, slipping wordlessly into the system? As we learn from Roman’s actions, the interest of the person who is lying on the ground supersedes the importance of the law.

The scenario harkens to the parable of the Good Samaritan, with an emphasis on the systems of oppression (police, how the government engages with the homeless community) that harm people, even after their death. Not only was this an emotionally effective moment, but it showed, rather than told, the nuance and importance of true activism, even when you’re not marching or protesting—even in private.

What happens when we lose our fire for the cause?

For Roman and Maria, questions surface about people who have been doing the work of activism long-term—both in public and in private. What happens when we lose our fire for the cause? Or what happens when we give into the system? At one point, Roman says he is “tired of doing the impossible for the ungrateful.” As a person of faith who is also passionate about justice work, I’ve found that my motivating force is my understanding of the example of Jesus. I’m often tempted to give in and simply live an easy life, yet a sense of calling toward something greater than myself beckons me back towards advocating for the marginalized. I often have to be reminded that a group of people united for the welfare of another can bring about social change.

Roman attempts to create change in a vacuum for a large portion of his life. Sure, he chips away at his work, but in the end he needs community to discover the fullness of what he has to offer. It’s interesting that in individual cases, Roman’s relentless pursuit of true justice—often with a disregard for the parameters of legal proceedings—wreaks havoc. Things fall apart, and often Roman’s efforts result in the very injustice he seeks to rectify.

Though his individual pursuits result in roadblocks, Roman finds a greater measure of success when he begins to tackle not just individual cases, but also the unjust system itself. Perhaps that’s the most important takeaway that Roman J. Israel, Esq. offers its viewers: justice is most often attained when we seek to dismantle oppressive systems, with others, in community.

Joe Tatum is the Philadelphia City Director for City Service Mission, a long-term volunteer with CineSPEAK, an Oriented to Love alumnus, and an avid consumer of high-quality film.