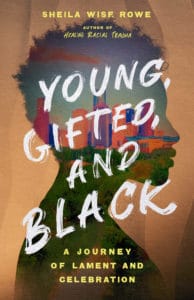

This month, we will be introducing you to some incredible Black authors and thinkers who are helping us find a pathway to sustainable peace-building, ongoing reconciliation, and honest reflection. Today we talk with Sheila Wise Rowe, the author of Healing Racial Trauma and the upcoming Young, Gifted, and Black, which releases this month through InterVarsity Press. Sheila holds a master’s degree in counseling psychology and has ministered to abuse and trauma survivors in the United States for over 25 years and in Johannesburg, South Africa, for a decade. She has also taught counseling and trauma-related courses. Sheila and her family live in the Boston area, where she is a writer, speaker, and spiritual director.

This month, we will be introducing you to some incredible Black authors and thinkers who are helping us find a pathway to sustainable peace-building, ongoing reconciliation, and honest reflection. Today we talk with Sheila Wise Rowe, the author of Healing Racial Trauma and the upcoming Young, Gifted, and Black, which releases this month through InterVarsity Press. Sheila holds a master’s degree in counseling psychology and has ministered to abuse and trauma survivors in the United States for over 25 years and in Johannesburg, South Africa, for a decade. She has also taught counseling and trauma-related courses. Sheila and her family live in the Boston area, where she is a writer, speaker, and spiritual director.

What do you see in this generation that compelled you to speak hope into their lives?

This generation of Black millennials and younger adults is not a monolith. They have similarities and differences in processing their Blackness, Americanness, giftedness, and faith. We are all unique, gifted, and at-risk in one way or another. And we certainly need more initiatives to help those most at-risk identify and nurture their gifts and aspirations.

Yet, there are Black millennials and younger adults who are at-risk but in a different way than the usual understanding of “at-risk.” We celebrate them for their academics, arts, sports, trades, leadership, and entrepreneurship. They appear to be self-sufficient and high functioning, but they also need support.

I wrote Young, Gifted, and Black: A Journey of Lament and Celebration as a love letter to them. It seeks to help gifted ones see, hear, and validate their inner lives and experiences. This includes complexities such as lament, celebration, and becoming.

I hope my book will help gifted ones to embrace their whole story and discover they aren’t as alone as they thought, nor do they have to be perfect. They can hope again because, in reading stories of other gifted ones, they see how healing is possible. They also discover how the Lord is committed to strengthening them on the healing journey, and along the way, there will be friends and helpers.

You talk about the South African concept of Ubuntu: what is that, and why is it critical to find a pathway for young, gifted, Black women and men?

The Zulu word Ubuntu loosely translated is “I am because we are.” Dr. Martin Luther King alludes to this in his “Letter from the Birmingham Jail”: “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.”

Black young folks who embrace and embody a posture of Ubuntu soon discover that to heal and move forward, they really need God and others. Black young adults are trying to find a footing in their families, communities, this country, and around the world. They need support, especially as they grapple with issues around race, equity, reconciliation, mental health, and revolution.

Over time, gifted ones can help and comfort others with the help and comfort they receive. My book also aims to identify and better equip friends, parents, pastors, educators, and allies to walk with gifted ones as they pursue healing and more well-rounded lives.

Why is scripture critical for our navigation of trauma?

In 2 Timothy 3:16, we read how scripture empowers us. It instructs and corrects, gives us strength, direction, and leads us deeper into the path of godliness” (TPT). Increasingly, studies are validating the positive effects of scriptural principles and promises. The Scriptures can reveal how we show up authentically; and where we don’t and invite us to journey toward healing.

They tell how faith in God, who loves and strengthens us, can help us persevere, navigate, and overcome hardship and trauma. Most importantly, we have Jesus, who is familiar with our suffering, and in our time of need, we can boldly pray for help and wisdom.

As we reflect on Scripture, we gain insights and recognize joy, beauty, and blessings. We see how Emmanuel God has been, is, and will be with us, so we can celebrate how far we’ve come on the journey and where we are going.

What is the role of the local church in caring for and raising Black girls and boys, men and women, who deeply believe they can change our world?

Going forward, young activists will face indignities and trauma. The local church can be a safe harbor for Black girls and boys, young women, and men to find respite. Churches need training to better serve them and commit to being mental health advocates and anti-racists. With those skills, churches can help young activists heal fight another day. They can help build and nurture people, neighborhoods, and relationships, so they increasingly reflect God’s shalom–wholeness, justice, peace, nothing broken.

There are some critical elements that the local church can offer to foster this kind of shalom and community: listen, communicate, connect, and subversive celebrations.

When churches deeply listen and do not assume, they discover the individual and communal needs related to physical, mental, spiritual, and environmental health. Trust is built when they encourage open communication and value everyone concerned about best assisting gifted ones and the community. They can offer circles where gifted ones can lament and share their problems, grief, and pressures of being gifted.

They can also provide multi-generational connections where exchange and support are life affirming and powerful. Lastly, the church can be a place of subversive celebration where we remember and celebrate our faith and Black love and joy, all of which disarms and disrupts the peoples and narratives that seek to oppress.

Excerpt from Young, Gifted, and Black: A Journey of Lament and Celebration

Excerpt from Young, Gifted, and Black: A Journey of Lament and Celebration

The fighters on the front line are in the most visible position to combat the enemy. They are also at the most significant risk of capture or becoming a casualty. Young activists experience victories and face opposition and painful disappointments as they passionately fight injustice on the front lines. Shineika is such an activist.

Shineika’s story

Shineika says she was born a fighter and activist. She was raised in Haiti until 2010 when a devastating earthquake rocked the country. It is estimated that three million people were affected and many of the over three hundred thousand who died were buried in mass graves. Almost one million people were left homeless; some slept in donated tents while others were forced to scavenge for materials to create shelter. Shineika and her family, left broken and devastated, sought a visa to come to the United States. Because they had relatives already living here, they were able to immigrate.

By the time Shineika started college, she’d been in the United States for less than ten years.

As a clearly gifted student, speaker, and activist, Shineika experienced the physical and emotional strain from doing too much and running at a high level of excellence. The bar is set high, and she has internal expectations that she must maintain this high standard. After graduation, Shineika plans to apply to law school to become a civil rights attorney on the frontline serving people on society’s margins. Like so many of us, the balance between being and doing is hard to maintain.

Shineika’s plans shifted before the second semester ended as the Covid-19 was raging across the United States. Like many other colleges, Shineika’s closed and offered only virtual learning. She took it as a time to refocus, connect with God on a deeper level, and read a lot. Then less than a couple weeks later, George Floyd’s murder was captured live on video. Like many of us, Shineika was traumatized.

Although she felt the need to do something, she resisted due to Covid-19. However, every morning at 6:00 a.m., she felt prompted to pray. Shineika was still afraid, but then one day while praying, she felt a release to organize a protest in her town. Thousands showed up; almost the whole city marched in support of Black lives. Shineika was one of the front-line activists prominently featured in the press. She was quoted as saying, “We are fighting all the way. No matter how long it takes. This is not just a Facebook post. This is not just an Instagram post. It is our work. It is what we do.”

She later organized her peers to attend the city council meeting via Zoom to demand the statue of Christopher Columbus in the center of town be removed. Several opposers logged into the Zoom call and referred to them as hoodlums and all manner of disgusting words. However, the council voted to remove the statue, and when it came down, the Native American community celebrated on that spot.

After a long and traumatic summer, Shineika looked forward to returning to campus to resume her coursework and duties as the newly elected student council president. Because she supported the Black Lives Matter movement, the backlash on social media was swift. Shineika was accused of divisiveness and told that White supremacy and systemic racism no longer existed in America.

The social media slander was followed by a racial epithet found in her dorm. When it was discovered, Shineika broke down in her dorm hallway, doubled over in pain. She screamed uncontrollably. Her pain was not just about that incident; it was about all that happened in the spring and summer. It was about the murders and protests. It was about the two occasions the police stopped her and the terror she felt when they demanded her license and registration, asking if her two-year-old car was a stolen vehicle. All of this left her feeling unsafe and unsure of whom to trust.

Soul care

Soul care is essential to go the distance in the reality of the highs and lows of activism.

Research has shown that activists like Shineika can despair when efforts to reform fall short: “They seek equity, justice, and truth, and attempt to put these into place via unrealistic reforms and goals. The inability to make a difference may cause them to feel frustrated, angry, and depressed, and may also cause them to feel guilty because they have survived.”

November 18 was a difficult day for Shineika, given the racist incident on her campus. Then she was reminded that it was the date that her people, the Armée Indigène (Indigenous Army) defeated the French colonizers at the Battle of Vertières to obtain their independence. Shineika realized that, like her people, she has to keep fighting for justice, and the best way she would do that and get through life was by trusting and listening to God. This stance helps gifted front-line activists avoid burnout; so will including good soul care.

Shineika hears for herself Jesus’ reply to Martha about her sister Mary in the gospel of Luke: “You are worried and upset about many things, but few things are needed— or indeed only one. Mary has chosen what is better, and it will not be taken away from her” (Luke 10:41‑42). Mary models a balanced woman. Her priorities were straight; she knew how to engage in soul care. She knew there was a time to be and a time to do, and that time with Jesus was a time to be. The Lord had come to stay, and she soaked up his presence. This is a word for all of us to go and sit at Jesus’ feet. Unlike the busyness and the works that may or may not be well received, what we gain in this posture will not be taken from us, though often it is hard to stop doing and to just be.

A recent study found that burnout was prevalent in activists who felt responsible for eliminating structural racism. The burnout came after the fight to overthrow structural, systemic racism and White supremacy became overwhelming and seemingly impossible. Some activists burn out after experiencing backlash for their activism, putting their employment or bodies at risk. Other activists of color attribute their burnout to being overwhelmed by everyday experiences of racism and micro-agressions, while others were disillusioned by White allies who engaged in group power struggles with activists of color. Like Shineika, we begin to recognize that the Lord strengthens us to accomplish all that we do, but we can only push our bodies so far. As we submit to his loving care, we see that our healing rests on our relationship with God. So, we surrender our way of being and doing to him. We renounce the belief that our worth is found in how well we do or do not perform. The Lord increases our capacity to be and our power to do in a more balanced way. And he invites us to rest and play.

When we engage in healthy soul care, we know when and how to rest, de-stress, expose injustice, and advocate for our own needs and the needs of others. All of these help us to build resilience. Our soul care builds on what has worked in the past and in the present, on ways that create stability and recognize that in Christ we are and have more than enough. When we pray for forgiveness for ourselves and receive it, we are released to renounce the ways we remain captive to a state of perpetual doing.

The Scriptures also tell us to forgive our enemies, not just seven times but “seventy times seven” (Matthew 18:22), though we may still struggle with this while pursuing justice. We may fear that forgiveness means no accountability or justice. However, when our hearts are open, we can release bitterness and unforgiveness, allowing the Lord to render judgment and bring justice in his own way.

Adapted from Young, Gifted, and Black by Sheila Wise Rowe, this excerpt appears by kind permission of InterVarsity Press (Downers Grove, IL). Copyright 2022 by Sheila Wise Rowe.