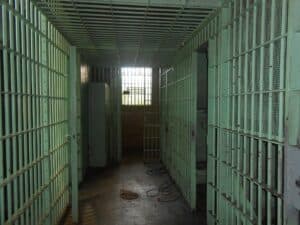

Inside most of the local jails, state and federal prisons, and detention centers that dot the landscape of the United States, on any given day, tens of thousands of incarcerated adults and youth are held in solitary confinement. For 22 to 24 hours a day, they are confined to a cell the size of a parking space for months, years, even decades. Meals are shoved through a small slit in a solid steel door. The cell may or may not have a window to the outside world. Those who have experienced this extreme isolation often describe it as being “buried alive.”

The United Nations and other developed countries consider prolonged isolation a form of torture. Solitary confinement often leads to self-harm and suicide, due to a lack of meaningful human contact. Such extreme isolation changes the chemistry of the human brain. As those in solitary suffer, so do their families and loved ones. Corrections staff working in such toxic environments experience levels of PTSD similar to veterans returning from war. Yet in the US, the practice is used arbitrarily and often.

Solitary confinement goes by many names, including restrictive housing, room confinement, isolation, segregation, the hole, and the box. Judges and juries do not determine whether a person will be placed in isolation: that decision is left to the sole discretion of corrections staff. And isolation is not a punishment reserved only for those who threaten themselves or others—it is also used in response to non-violent infractions of prison discipline, and for individuals with severe mental illness, LGBTQ individuals in “protective custody,” the elderly, and youth in adult facilities. Over the course of one year, it is estimated that nearly 1 in 5 incarcerated people in the US spend time in solitary confinement, totaling roughly 400,000 people annually. Most will one day return home to our communities, profoundly damaged by this costly experience. Additionally, racial disparities, profound at every level of the US criminal justice system from initial contact with law enforcement to harsher sentencing and conditions of confinement for people of color, extend to solitary as well, with a disproportionate number of people of color held in solitary confinement.

Isolation is not a punishment reserved only for those who threaten themselves or others. It is also used…for individuals with severe mental illness, LGBTQ individuals in “protective custody,” the elderly, and youth.

The harmful impact of solitary confinement has been recognized throughout history. In 1829, the Eastern Pennsylvania Penitentiary became the first prison to open in the United States with solitary cells. It was called a penitentiary with the idea that those who were held in isolation would deeply contemplate their crimes, and become penitent. Rather than becoming remorseful, though, those subjected to isolation quickly developed serious mental health problems, with many going insane. In 1842, Charles Dickens visited the facility and wrote, “The system here is rigid, strict and hopeless solitary confinement. I believe it…to be cruel and wrong. I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain, to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body.” The practice was largely abandoned in the 20th century. In 1890, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a man should be freed after being subjected to one month in solitary confinement. Even if the man had been convicted of murder and sentenced to die, the court ruled that the burden of one month in solitary confinement was such a devastating redress, it warranted granting his freedom.

The widespread return of solitary was a complex process. A dismantling of the mental health system without community-based alternatives, “tough on crime” criminal justice policies, mandatory minimum sentencing and the rapid expansion of for-profit prison and detention have all contributed to the rise of mass incarceration in the United States over the past forty years. The result is the largest incarceration system in the world, as well as the highest rates of solitary confinement globally. Yet there was no public call for an expansion of solitary confinement. Instead, a lack of both independent oversight and public engagement led to the creation of a widespread system of prolonged and indefinite isolation.

Today, calls for humane alternatives to solitary confinement are coming from unlikely allies—including the Association of State Correctional Administrators (ASCA), Republican and Democratic Governors, and a growing list of Supreme Court justices. Medical and mental health professionals have joined calls for an end to solitary, recognizing the public health impacts of isolation on families and communities. Interfaith religious leaders and faith communities have joined these efforts, making the moral case for an end to solitary. Through testifying to the horrors of solitary first-hand, currently and formerly incarcerated people and their loved ones have led the way in this groundswell. State by state, campaigns to end prolonged isolation are advancing.

People of faith have an important role to play in the growing movement to abolish solitary confinement. The National Religious Campaign Against Torture (NRCAT) has developed resources and action steps you and your faith community can take to support efforts to promote humane alternatives.

Here are some ways you can get involved:

- Host a screening of NRCAT’s documentary, Breaking Down The Box to hear from survivors of solitary and see how faith communities are joining them in efforts from coast to coast.

- Organize a vigil to speak out against solitary confinement and stand with survivors. Read and share first-hand accounts shared by Solitary Watch.

- Host a letter-writing campaign to your legislators to call for an end to solitary. Share with them the alternatives to solitary that are being implemented through the Vera Institute of Justice Safe Alternatives to Segregation Initiative.

- Host a chalk-in: Draw a 6×9 foot box with chalk and sit in it, symbolizing the average dimensions of a cell where people spend 23 hours a day for months, years and decades in solitary.

- Share photos and updates about your action on Twitter and Facebook. Follow us at @nrcattweets and use the hashtags #STOPsolitary #together

- Host a book club series on Hell Is A Very Small Place, a collection of powerful first-hand accounts from solitary.

- Sign and share the NRCAT Statement Against Prolonged Solitary Confinement.

Earlier this year, on Holy Thursday before Easter, Pope Francis visited the Paliano detention center, a maximum-security prison in his backyard, just outside Rome. He went to wash the feet of the incarcerated, including a visit to those in solitary confinement. His actions speak the words we are each called to preach through our living.

How will you wash the feet of those in isolation, and join the growing call to end the torture of solitary in your community?

Laura Markle Downton is campaign strategist for the National Religious Campaign Against Torture.

4 Responses