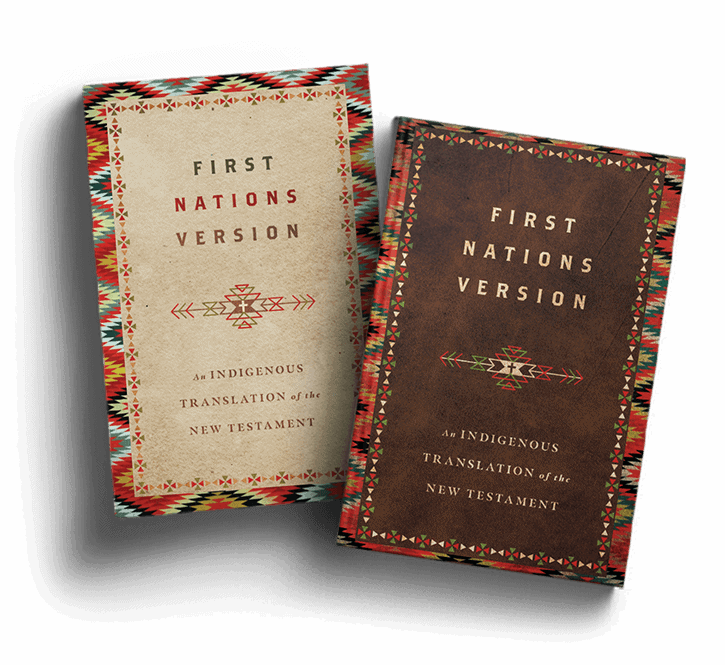

Intervarsity Press has just published the First Nations Version: An Indigenous Translation of the New Testament. We talked with Terry M. Wildman, who served as lead translator, general editor, and project manager of the First Nations Version (FVN). Wildman also serves as the director of spiritual growth and leadership development for Native InterVarsity and is founder of Rain Ministries. Here we talk about how this Bible version came together and some of the challenges First Nations people are facing today.

Intervarsity Press has just published the First Nations Version: An Indigenous Translation of the New Testament. We talked with Terry M. Wildman, who served as lead translator, general editor, and project manager of the First Nations Version (FVN). Wildman also serves as the director of spiritual growth and leadership development for Native InterVarsity and is founder of Rain Ministries. Here we talk about how this Bible version came together and some of the challenges First Nations people are facing today.

Tell us about the process of putting this new First Nations Translation of the Bible together. What did the editorial process look like?

In the Fall of 2015, our Translation Council gathered (with leaders from OneBook of Canada and Wycliffe Associates) in Florida for a week, and then in Calgary, Canada, for three weeks. We spent one week establishing how we would translate over 180 key terms used in the New Testament. We also determined how the translation process would proceed.

Since I had been working for several years developing the writing style, it was decided that I would prepare the initial draft of each book. I would then invite several reviewers to give feedback using Google Docs. When the review was complete, the text would be entered into ParaText, a software developed for Bible translators. Checks were made in reference to the key terms and other translation requirements.

After each segment review was finished, it was then turned over to David Ohlson, the FNV consultant (David is the former director of Wycliffe Canada and OneBook), who has more than 45 years of translation experience worldwide. David carefully checked each verse against other English translations and, when necessary, looked into the original Greek. The feedback was then given to me for revision. Final checks were run through ParaText again to prepare the text for publication or future revision if needed.

The FNV recounts the Creator’s Story—the Christian Scriptures—following the tradition of Native storytellers’ oral cultures. Talk to us about why it is important to integrate the traditions and cultures with God’s Word.

The FNV recounts the Creator’s Story—the Christian Scriptures—following the tradition of Native storytellers’ oral cultures. Talk to us about why it is important to integrate the traditions and cultures with God’s Word.

Many of our Native Nations still resonate with the cultural and linguistic thought patterns found in our original tongues. This way of speaking, with its simple yet profound beauty and rich cultural idioms, still resonates in the hearts of Native people.

We all learn best within the context of our own languages and cultures. All translations take this into account in one way or another, some less and others more. The many English translations we have are needed to adapt to changes in culture and language as communities develop in different regions. Since over 90 percent of our Native people no longer speak or read their original language, we try to capture linguistic thought patterns in English for the FNV.

The FNV takes into consideration contextual word choices, idiomatic expressions, and modifications in paragraph and sentence structure that clarify and facilitate understanding of the Scriptures. Our priority has been to maintain the accuracy of the translation and its faithfulness to the intended meaning of the biblical writers within a First Nations context.

It is not a word-for-word translation, but rather it is a thought-for-thought translation, sometimes referred to as dynamic equivalence.

Please share an example of how changing the text of a passage can speak more readily and powerfully to First Nation’s people.

The FNV doesn’t change the text; instead, it uses word choices that correspond to the meaning of the original Greek text. One of the most notable and powerful choices we made was to translate the meaning of the names of people and places. For example, Jesus is “Creator Sets Free,” Abraham is “Father of Many Nations,” Paul is “Small Man,” and Jerusalem is “Village of Peace.”

This corresponds to the traditional naming practices of First Nations people, and each name has a meaning. The translated meaning is derived from the Greek and Hebrew meaning of the names.

Another example is our translation of the word “sin.” For many of our Native people, the English word “sin” evokes the memories of boarding school, where “sin” was often the length of our hair, or speaking in our native language, or anything related to our cultures. The biblical concept of sin is expressed in the Greek word hamartia, which means “to miss the mark” or “to fail to do what is right.”

All human beings are broken and fail to live in Creator’s ways. Some try but fail, some don’t even try, and others give themselves over to evil ways. We have translated “sin” as either “bad hearts,” “wrongdoings,” or “broken ways,” depending on which one best fits the context.

You have a ministry called Rain Ministries that you founded with your wife. What is that and how are you educating and inspiring both First Nations people and the broader church through it?

Rain Ministries is our Arizona-based non-profit corporation founded in 2001. Through this ministry, Darlene and I are dedicating our time and the gifts Creator has given us to serve the First Nations People of North America; working and praying to see dignity and harmony restored to individuals, families, clans, and tribal nations. We believe that the message of Creator’s Son Jesus is for all people and will transform the lives of all who follow Him. But we also believe that the message must be embraced within the context of every culture to be effective.

Rain Ministries is the home of RainSong Music and the First Nations Version, where we have produced six music CDs and four books that provide a bridge between cultures. As RainSong, we have traveled for over 20 years working at bridging the gap between the Christian churches and Native communities. I have written a book on healing and reconciliation called Sign Language: A Look at the Historic and Prophetic Landscape of America. We have also created a children’s book called Birth of the Chosen One, and a harmony of the Gospels called When the Great Spirit Walked Among Us. Both Darlene and I volunteer as staff for Native InterVarsity as Elders in Residence mentoring the younger First Nations staff.

Share one big obstacle First Nations people are facing right now as well as one blessing. What is encouraging you personally these days?

One big obstacle facing our First Nations people is the number of Native girls becoming victims of sex trafficking in the U.S. Nearly 40 percent of all female sex trafficking victims are First Nations women.

One blessing is the increasing number of First Nations people being elected or placed in governmental positions of authority in the U.S.

I have been personally encouraged by the overwhelmingly positive response to the FNV New Testament and by its use in ministry at Cru Nations and Native InterVarsity. I just received a phone call from Pastor Casey Church of Good Medicine Way, a contextual Native church in Albuquerque. He told me they are using the Gospels and Acts as their preferred translation. That feedback and my role in helping to mentor young Native staff at Native InterVarsity have been both fulfilling and encouraging for the future of Native ministry.