Editor’s note: Recent conversations about the ethics (and dangers) of “voluntourism” reminded us that these issues are as relevant today as when PRISM magazine first ran the following article in 2013. Do you have thoughts on voluntourism? Drop us a line; we’d love to hear from you!

There’s no doubt the church cares about orphans. For decades we’ve prayed, given money, and participated in international campaigns for “AIDS orphans” in Africa. We’ve supported orphans through child sponsorship, participated in drives to supply orphanages with items such as school supplies and clothes; and many of us have at one time or another gone on a short-term mission trip focused on caring for orphans in an orphanage or children’s’ home. And why not? The Bible is clear that God cares about orphans. In fact, God demands that we care and advocate for the “fatherless” and “widow” (e.g. James 1:27, Isaiah 1:17), just as God cares for us. Whether it’s a concern for local foster children, orphans in Asia, or other vulnerable populations, it is our duty to be concerned for men, women, and children who have lost their families.

When it comes to orphans, however, what the church hasn’t done particularly well is take heed of what history and research have to teach us about child development, child protection, and what it means to live in a sustainable and healthy family environment. Instead, we continue to hold on to the belief that the best way to help is through an orphanage model in which we (the church) care for orphans ourselves.

“When people start an orphanage, they tend to focus on the needs of the most vulnerable children… What we’ve found through our research was that vulnerability was not taken away as the children grew up. It was actually just delayed until the children left. In Cambodia, there are not orphanages because there are orphans, there are orphans because there are orphanages. The vast majority of the children living in orphanages in Cambodia have parents, have family, and the fact that they’re in the orphanage separates them from their families, alienates them from their communities to such an extent that when they leave the orphanages they are no longer part of those families.”

– Sarah Chhin, country advisor for Project Sky

Certainly, vulnerable children are in need of safety, care, and support; however, the idea that the primary way to do this is by building more orphanages and/or welcoming volunteers from overseas to “love” and work with orphans—regardless of the “good intentions” behind doing so—is not only antiquated (and somewhat biased) but also can be downright harmful. Research dating all the way back to the 1950s1 presents clear evidence that both orphanages and orphanage “tourism” can have serious detrimental consequences, not only for children but also for the community at large. And yet the Western church has played an active role not only in funding orphanages where they may not be needed but also in encouraging “orphanage tourism” disguised in the form of short-term mission trips.

A last resort

Please don’t misunderstand. In some cases, an orphanage model may be necessary, especially following a natural disaster or as a short-term solution when alternative safe housing for a child cannot be found. However, the reality is that in most cases there are alternative family solutions to institutionalization, even in developing countries,2 and orphanages should be considered a last resort. This is by no means a condemnation of the church’s involvement in overseas ministry or of Christians’ motives for helping orphaned children. Rather, we’re suggesting that we begin asking ourselves some challenging questions. “Why are orphanages unacceptable for children in my country, but acceptable for children in the developing world?” “Would I ever want my child to end up in an orphanage?” “Why do I visit orphanages?” “Is it in the best interest of children to have strangers and visitors coming in and out of their already unstable lives?” “What happens to the children once they become an adult and have to leave?”

Over 60 years of global research has demonstrated many adverse impacts of residential care (orphanages) on the development of children, including personality disorders, growth and speech delays, and an impaired ability to reenter society later in life.3 Orphanages have also been shown to place children at serious risk of physical and sexual abuse. Orphanages often turn to international donors and volunteers in hopes of raising money. As a result, short-term volunteers, who have not undergone background checks, are frequently given access to children, posing a significant risk to child protection. In addition, due to a high turnover of caregivers, children must repeatedly try to form emotional connections with different adults. When volunteers leave, these bonds are broken and children experience abandonment once again.4

One common misconception is that children in orphanages are “double orphans” (meaning both parents are deceased) or do not have families. The truth is, however, that because so many orphanages are funded by international donors who also provide good food and education, many children are in orphanages for other reasons, such as poverty, and many are brought to the orphanage by their own parents. These parents, often facing extreme poverty, illness, or lack of education, believe that by placing their child in an orphanage they are providing them with opportunities for a better education. It is not true that these families simply abandoned or do not care for their children. In many cases, they simply have no better alternative, especially in countries where there are few social services.

In Cambodia, for example, a 2011 study5 found that 44 percent of children in residential care were brought by their own parents, and 61 percent have at least one living parent or close relative. The single most contributing factor for placement in residential care was education, with 90 percent of those in the community saying they thought a family member should send a child to an orphanage for education if they cannot afford the local school. Contrary to the Royal Government of Cambodia’s recent policies stating that family and community-based care are the best options for children and that new residential programs should not be encouraged or pursued, the number of children in orphanages has increased by 75 percent since 2005, and the majority of these children were accepted by nonprofit international organizations (as opposed to the government). According to the same government database, over 45 percent of children placed in residential care since 2005 were placed there primarily due to poverty and not because they did not have living relatives. Ironically, Cambodia has a long tradition of caring for children through kinship care with extended family, but the rapid proliferation of residential care facilities threatens to erode these existing systems, placing more children at risk.

By investing in institutionalized care as opposed to alternative solutions such as foster care, kinship care, or by assisting families through community development (providing access to education, vocational training, employment, micro-finance, etc.), we perpetuate a reliance on institutions instead of family. Children who could otherwise remain in a natural family setting are instead placed in risky situations where their development and safety may be compromised. Advocates for community-based care argue that these alternative solutions are not only more cost-effective but are also much more sustainable and provide families with the opportunity to care for themselves without depending on international aid programs.

Orphanage tourism

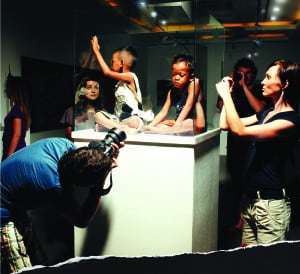

Orphanage tourism generally refers to Westerners who visit or volunteer to work at a residential care center (orphanage) in the developing world. These trips can be arranged by a tour or travel company, a nonprofit, or by a church and can mean anything from one person dropping in to visit children at an orphanage for a few hours or a group of a dozen people coming to work at the orphanage for several weeks or months. Sometimes visitors and volunteers pay the orphanage a “donation” to visit, or sometimes the group may pay the orphanage to stay on the premises during their visit. Orphanage tourism includes many different scenarios and generally occurs out of good intentions. Regardless of intentions, however, orphanage tourism can be extremely harmful and is usually not in the best interest of children.

In worst-case scenarios, orphanage tourism leads to significant misappropriation of funds. When tourists or groups visit an organization in a developing country, they are encouraged to leave a donation for the operations and programs of the organization. In some cases, the donation is redirected—not to the children or to the costs of the orphanage but into the pockets of opportunistic directors or leaders.6 In addition to requiring children in the orphanage to dance, sing, or perform for visitors (sometimes under threat of violence or neglect), there have also been cases in Cambodia of orphanage leadership sexually exploiting children in their care.7

Unfortunately, abuse and exploitation occur not only in orphanages where directors and leaders have self-serving intentions. Because of the lack of regulation and accountability in orphanages, abuse and neglect are often rampant. Orphanages that accept visitors or volunteers (regardless of whether they know them or not) overwhelmingly lack proper screening for people visiting their facilities. This can have multiple ill effects. First, the easier it is to access these children, the more people will do so. The higher the demand for these types of opportunities to visit an orphanage, the more orphanages will consider allowing visitors and even opening new orphanages. Because nonprofits and ministries are often competitive in their need for funds, it can be difficult to resist the wants and desires of potential donors. Second, easy access to children in orphanages means easy access for everyone—including predators, child sex tourists, and pedophiles who seek out vulnerable children. Predators rarely look or seem “dangerous” and can usually win the trust of groups who believe all volunteers have equally good intentions.

Even if visitors are not directly abusing children they are often not equipped to interact with traumatized or vulnerable children, and their well-meaning involvement can actually increase a child’s vulnerability to abuse in the future, especially if they perceive all Westerners as safe and well-meaning.

Personal motivations

Perhaps you’re thinking, “But I’m not going to visit just any orphanage. I’m going to my friend/church/known organization’s orphanage, so I will not fall into these voluntourism traps.” Perhaps you are moved by supporting or visiting an orphanage because it closely parallels your idea of a perfect vacation8 because you can connect with local children in a way that simply having a tour guide or purchasing goods from a shop owner does not afford. Or perhaps you simply want to help. Unfortunately, however, the reality is that orphanage tourism—regardless of how happy the child seems or how big a donation you give to the organization—is not a true connection between peers. The children you visit will likely never have the opportunity to reciprocate a visit, nor do they really have a choice about meeting and spending time with visitors. Your visit is much more about your emotional desire than it is about what the children need to be healthy and/or happy.

Before thinking about visiting an orphanage, honestly consider your motivations. What are you going to get out of your visit? Is your visit in the children’s emotional best interest in the long-term? How would you feel if the situation were reversed? Is there a way you can better support these children that doesn’t include a visit? Without a thoughtful, clear perception of your own ideas, you will not be equipped to develop awareness regarding the stereotypes to which you subscribe, and you will limit any deeper understanding of global inequalities that your trip may try to address.9

Conclusion

Based on the reasons we’ve outlined here, we do not believe orphanages are the way forward for children. But what does this mean? How can the church be part of the solution?

Thankfully, many ministries and organizations around the world have realized the shortcomings of orphanages and are working on innovative solutions to ensure orphans are cared for in safe and loving families. (See “Finding Alternatives,” below.) The journey toward change is never easy, however, the more the church commits to understanding how we can better serve others, the more likely we are to succeed.

Tania DoCarmo and Charlie and Julia Smith-Brake work for Chab Dai, an international Christian organization dedicated to addressing abuse and human trafficking in Cambodia, the United States, Canada, and other partner regions. For more info, go to ChabDai.org.

(Watch the 14-minute investigative video Ultimate Betrayal: Cambodia’s Orphanage Scandal, which clearly shows how the rapid growth of poorly run charities in Cambodia is putting children at increased risk of sexual exploitation and abuse.)

Finding Alternatives

The following resources and organizations are focused on innovative solutions in Cambodia and beyond:

Children in Families is a nonprofit based in Cambodia that is concerned with the over-institutionalization of at-risk children. It seeks to place children who cannot be reunited with their birth parents with loving families through kinship care (in the homes of relatives) or long-term foster care.

Cambodia’s Orphan Business, an Al Jazeera Special Report, is a 25-minute investigative video that looks critically at the exploitation of children from unscrupulous businessmen and international organizations who use orphanages and orphanage tourism for their own financial gain.

Orphanages Not the Solution is a resource for tourists, visitors, and those looking to volunteer in Cambodia to help them make informed decisions about their interaction with and support of orphanages in Cambodia.

Uniting for Children uses stories and articles to expand the conversation with those directly involved with at-risk children worldwide about the best way to care for these children. Be sure to watch the poignant “Why Not a Family?” video on the homepage.

Endnotes:

1. John Bowlby, Maternal Health and Mental Health (World Health Organization, 1952).

2. David Tolfree, Roofs and Roots: The Care of Separated Children in the Developing World (Save the Children UK, 1995).

3. A. Gomez de la Torre, D. Griffith, D. Tolfree, et al, Scaling Down: Reducing, Reshaping and Improving Residential Care Around the World (Every Child, 2011).

4. John Williamson and Aaron Greenberg, Families, Not Orphanages (Better Care Network, 2010).

5. Jordanwood, C., Lim S., Chinn, S., With the Best Intentions: Study of Attitudes Towards Residential Care in Cambodia (UNICEF, 2011). All data in this paragraph comes from this same study.

6. See Al-Jazeera’s “People & Power: Cambodia’s Orphan Business.”

7. Robert Carmichael, “UNICEF Concern Prompts Cambodian Investigation of Orphanages,” Voice of America, March 22, 2011.

8. P. Jane Reas, “‘Boy, have we got a vacation for you’: Orphanage Tourism in Cambodia and the Commodification and Objectification of the Orphaned Child.”

9. Claire Dykhuis, “Youth as Voluntourists: A Case Study of Youth Volunteering in Guatemala,” Undercurrent Journal, Volume VII, Issue III: Fall/Winter Issue 2010.

6 Responses

really appreciate the article- thank you. I totally agree. I work in Child Protection In East Africa and it is not uncommon for (normally) Americans to pitch up ‘on a call from the Lord’ and build an orphanage which bears little resemblance to the kind of home any normal child would live in- ie has washing machine and a/c.

am very concerned about the lack of screening involved to and am aware that NG0s targeting vulnerable children can be soft targets for offenders.

It also amazes me that donors happily give to the ‘exotic’ poor thousands of miles away but at the same time despise the poor in their own neighbourhoods and resent any government social protection.

In general, I think I agree with the premise of the article, that own families, even in worse conditions, are better for children, than nicely resourced residence care (orphanages). However, the authors engaged in scare tactics concerning pedophiles and child abusers coming in the doors of orphanages in the name of short term missions. Yet no data, nor even one anecdote, was provided to substantiate this concern. Therefore, I have a sneaking suspicion that the motivations behind this article have not been fully revealed. There’s money somewhere…maybe it’s an effort to divert orphanage money to an own organization?

I totally agree with Mark’s comments. It would be a nice balance to find the statistics of children who have been bounced around the foster care system and abused. There are no easy answers.

First let me give some of my background in that my wife and I run a home for children (personally I don’t like the stigma attached to the name orphanage). We have a missions background and have lived and worked in Asia for 30 plus years. As a Christian who has tried to listen to the Holy Spirit we began our home, Happy Horizons Children’s Ranch in response to the thousands of “street children” who were at risk kids, living most of the time on the streets of Cebu, Philippines. We had done many outreach programs via our local church to answer the question of loving the least of these and after one such outting involving many street kids I felt a special calling to “give them a home”. The key issue for me and my wife is “what do you do with children at risk”, facing a toxic environment daily, being sexually abused, hungry and alone for most of the day, forced to scavenge, etc.? No one wants them, care givers are part of the problem if not the problem, and they are facing life in “hell”. The answer for us was get them a safe place to grow up. I have done a lot of praying, research and have twenty years of practical experience, and most of what you say must be contexualized at best, and frankly is nonsense. It is interesting to me that for most if not all of those running homes for kids at risk, at least as Christians we have all answered a very personal call. History is full of examples of Christians gathering unwanted and thrown away kids, nurturing them as Jesus would do, and giving them the love and care they desperately need. It is truly what Jesus would do and has called us to do. If tomorrow you closed down every Christian Children’s Home, where would you place these children, most who have been sexually abused, trafficked, worked as slave labor and other hellish lives? So I call the church to fund these important homes, love those who labor unselfishly and volunteer a life time of service.

Respectfully,

Rev. Glenn Garrison