When you search for the words “the gospel of” in the New Testament, you’ll notice that Matthew finishes the phrase with “the kingdom.” Luke likes to talk about “the good news of the kingdom.” This news is the central message of Jesus: “news that will bring great joy to all people” (Luke 2:10).

When you search for the words “the gospel of” in the New Testament, you’ll notice that Matthew finishes the phrase with “the kingdom.” Luke likes to talk about “the good news of the kingdom.” This news is the central message of Jesus: “news that will bring great joy to all people” (Luke 2:10).

The news Jesus preached was about a place more than a profession of faith. It is a realm, not a religion. More of a nation than a denomination. The gospel has dimensionality—materially, economically, socially, and politically. An outpost of heaven located on the earth. Sometimes we get a taste of it here on earth. I’ve been to one such place, the Kolkata slum community.

In the middle of a red-light district in Kolkata is a textile factory operated by a business called Joyya. In 1999 Kerry Hilton moved his family from New Zealand to that area. They wanted to establish God’s kingdom inside the largest red-light district in Asia. I have visited there on a couple of occasions and found myself standing inside the gospel.

The 250 formerly prostituted women chattered away as Kerry and I walked around the factory floor. They were confident women, at peace with themselves and with those around them.

“They’re all paid the same wage,” Kerry told me. “Ten-hour days, and hard work, but it’s a living wage.” A living wage is good news to the economically marginalized.

Childcare is provided in the factory, along with a savings account and retirement plan. The workers begin each day looking at a Bible passage together and end the day with some reflection and snacks.

“I get requests for employment every day from women working on the streets,” he said as we wandered around the facility. “We can’t take them all in just yet. We’re competing with factories in China or Bangladesh which don’t pay as much and don’t use ethically sourced material or eco-friendly dyes. Their products are cheaper, but economic justice and environmental sustainability are important.”

Then, he shouted out to the women in the room, “What are we making?”

The women responded in unison, “Freedom!”

I realized then that these women were not sewing tee-shirts. They were sowing the kingdom of God on earth. They knew that the harder they worked, the more women who could join them. The gospel was a place, sitting inside a slum community, with none of the fauna and flora afforded to densely populated informal settlements. But this concrete building possessed more life and joy and peace than any wealthy, suburban neighborhood, even more than some church communities. It made such an impression that I wrote this poem as a tribute.

The Land of God

The kingdom of God is enchanting. That’s why I prefer the term “land of God.” It sounds like a land in a children’s story, and Jesus said we must become like a child to enter it. The land of God is mysterious, and it’s ruled by a benevolent king. It’s a world where strange and amazing things take place. The empires of this world exploit the vulnerable. Its economics reward those who plunder the environment. Money gravitates to the center while some people are pushed to the margins. In contrast, the economics in the land of God are centrifugal, pushing resources out to the edges. The social forces are magnetic, drawing the excluded into the center.

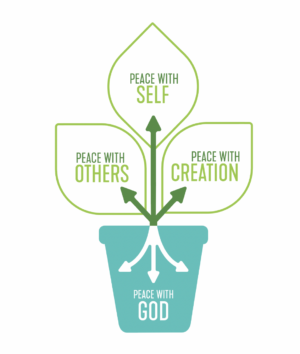

Immigrants are invited to pledge allegiance to the ruler of the land of God. And this nation-state doesn’t allow dual citizenship. You cannot pledge allegiance to the empires that rule this world and still be a citizen of the land of God, because one master will require you to love your enemy while the other may command you to kill your enemy. In the land of God, all things move toward shalom. Peace with God, peace with self, peace with others, and peace with creation. And while there may still be hardship and sin and imperfection, the land of God is always in the process of becoming.

Peace with God

Peace with God shapes our sense of well-being, our ability to form healthy intimacy with others, and our connectedness to creation. It is a primal peace, one for which all humans long. To experience this peace, we must acknowledge our acts of injustice, collectively and individually. The Divine One took on flesh in the person of Jesus to create a path to peace. In his victory over death and sin we are invited to trade our brokenness for Christ’s wholeness, our sin for his righteousness. Not all the women in the Kolkata textile factory identify as Christian, but a relationship with God is a value in that place. Peace with God serves as the pattern of shalom that rules all other relationships.

Peace with Others

The Creator exists in community with Christ and the Holy Spirit. This sacred community made us relational beings. Humans cannot procreate or thrive without profound connection with others. Our inter-dependence is a picture of the Trinity. To be true image bearers we must exist in harmony with others. Social harmony may never be completely experienced but the textile workers at Joyya are moving toward holistic, relational peace, acknowledging the ways they’ve wounded each other and extending forgiveness to those who’ve wounded them.

Peace with Self

Peace with self is made possible through peace with God, because we are forced to come to terms with our wounds and the ways we’ve wounded others. We cannot love ourselves unless we have told the truth about ourselves. Then we can recognize our frailty and brokenness while simultaneously embracing the Divine image we bear. We can honestly face our faults as well as our beauty. The voice of the inner critic is silenced by the voice of the Outer Advocate. God’s assessment of our value is the foundation upon which we can build a healthy love of self. The women of Joyya are learning to love themselves despite the way others have judged them.

Peace with Creation

Everything in the universe is a sibling to us humans, because we all share the same Divine parentage. The Genesis story locates humans as stewards of a garden. “Be fruitful and fill the earth,” God tells them. The Hebrew word for fill (mala) can also be translated “satisfy” or “fulfill.” There is something about our design that satisfies the earth. The forces of this world call us to exploit creation for our own gain, but the gospel is a place where humans bring life to the earth and animate fruitfulness. Leaders in the Kolkata textile factory care for the earth by ensuring that creation is respected in how they source their product or dispose of materials.

Holistic Peace

The gospel is a place where peace with God, peace with others, peace with self, and peace with creation is being advanced. I’ve seen it in Kolkata, India, and in places where citizens of God’s land are forging shalom inside the empires of injustice and oppression.

“Of the increase of his government and his peace there shall be no end.” Isaiah 9:7

Scott Bessenecker is Director of Global Engagement & Justice for InterVarsity Christian Fellowship. He began working for InterVarsity in 1986, shortly after gaining a degree in Business Administration from Iowa State University. Scott oversees InterVarsity’s work of sending college students to marginalized communities domestically and abroad where they encounter Christ and learn how to participate in holistic mission. His team runs InterVarsity’s Global, Justice, and Study Abroad programs. He created the Global Urban Trek—a summer immersion program for students to sojourn with those living in slum communities of the developing world.

Scott is author or editor of five books, most of which explore issues of global poverty. He received his Master’s degree in International Development from William Carey International University and hosts a blog and occasional podcasts on his website. He lives in Madison, WI, with his wife, Janine, who is a watercolor artist, and has three adult children, Hannah, Philip, and Laura.