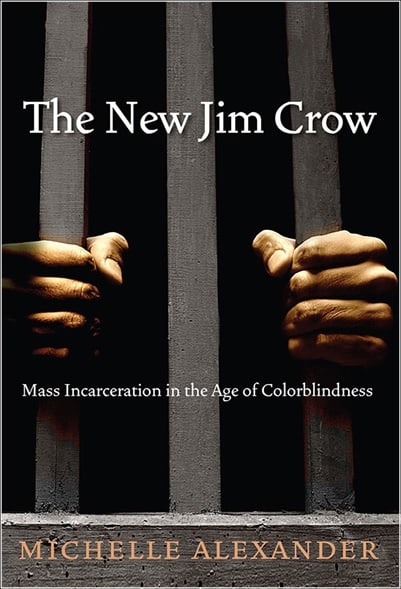

Editor’s Note: As we have run two articles recently that reference Michelle Alexander’s important work in The New Jim Crow, we are republishing this review for those who may want to learn more about the book.

During my youth in the 1970s, it was common among some African Americans to refer knowingly to what was then termed the “master plan.” While the phrase was never clearly defined for the uninitiated, the context within which it was used suggested that “the white man” had a grand scheme to continually subvert, oppress, and ultimately destroy the black race. A typical expression of this mindset can be seen in the 1974 film Three the Hard Way, in which white supremacists release into the nation’s water supply a toxin that is deadly to blacks but has no effect on whites. Notwithstanding the chuckles such apparent silliness engenders, as attorney and scholar Michelle Alexander observes, “The word on the street turned out to be right, at least to a point.”

In The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Alexander suggests, for example, that the CIA’s admission that it effectively permitted Nicaraguan rebels to smuggle drugs into the US during the Reagan years and distribute them in inner-city neighborhoods lends credence to urban conspiracy theorists who see a Nazi-like “final solution” in such actions. “Conspiracy theorists,” Alexander writes, “must surely be forgiven for their bold accusation of genocide, in light of the devastation wrought by crack cocaine and the drug war, and the odd coincidence that an illegal drug crisis suddenly appeared in the black community after—not before—a drug war had been declared.”

Thus does Alexander lay the foundation for her central thesis vis-à-vis the nation’s criminal justice system: Where there’s smoke, there’s fire.

In point of fact, The New Jim Crow is but the latest in a series of books and papers attempting to grapple with the conundrum that is mass incarceration. In the main, these studies review the same basic research, cite many of the same sources, and reach the same broad conclusions: To wit, mass incarceration dehumanizes those labeled as felons (and, by extension, their families) by denying them basic citizenship rights such as the right to vote, the right to serve on juries, and access to employment, public assistance, subsidized housing, and the like.

Moreover, though some come close, such studies tend to frame their conclusions in terms that fall short of accusing Uncle Sam of having a “master plan.” In other words, however harmful they deem the nation’s crime policies to be, the authors’ focus is chiefly on the policies’ effect, not on malicious intent.

Alexander, however, is different. In summarizing the impact of her experiences as an attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union on her view of the criminal justice system, she writes, “Quite belatedly, I came to see that mass incarceration in the United States had, in fact, emerged as a stunningly comprehensive and well-disguised system of racialized social control that functions in a manner strikingly similar to Jim Crow.” The leap from recognizing mass incarceration’s effect to alleging its intent is legally significant and, as a civil rights attorney, Alexander is well aware of its implications.

“Quite belatedly, I came to see that mass incarceration in the United States had, in fact, emerged as a stunningly comprehensive and well-disguised system of racialized social control that functions in a manner strikingly similar to Jim Crow.”

For more than a generation, the US Supreme Court has held that with respect to Fifth Amendment (due process) and employment discrimination claims, the burden of proof is on the plaintiff to establish that the actions of the defendant—in this case, the nation’s criminal justice system—were discriminatory in both effect and intent. Thus, Alexander’s statement that “We have not ended racial caste in America; we have merely redesigned it” is as provocative as it is damning.

The question is, does she prove her point?

To be sure, she makes a compelling argument. Alexander is particularly effective when recounting the pattern by which the subjugation of African Americans—through chattel slavery, the Jim Crow laws of the post-Reconstruction period, and, more recently, the so-called War on Crime—has, since the nation’s founding, served the political and economic needs of the power elite.

She maintains that the passage of civil rights legislation and the subsequent evolution of political correctness have rendered race-specific expressions of discrimination both illegal and culturally unpopular. Such expressions, she argues, have been replaced by (1) race-neutral language that achieves the same discriminatory ends; and (2) a series of court decisions designed to limit the impact of the legislation.

Such perniciousness, I fear, may likewise limit the impact of Alexander’s book. To be sure, her stated goal for writing it—“to stimulate a much-needed conversation about the role of the criminal justice system in creating and perpetuating racial hierarchy in the United States”—has already been achieved.

Yet, in reading it, I was reminded of a statement from Justice Lewis F. Powell in the Supreme Court’s 1987 decision in McClesky v. Kemp, a case which Alexander also cites. Writing for the majority, Powell determined that the overwhelming racial disparity of blacks versus whites on Georgia’s death row did not reflect unequal treatment under the law, and was thus not unconstitutional. As Alexander notes, the effect of the decision was to render irrelevant clear statistical evidence of discrimination in application of the death penalty.

Broadly applied, the court’s don’t-confuse-me-with-the-facts reasoning suggests that no matter how convincing her evidence—and it is persuasive—Alexander’s argument might ultimately be rejected. Thus, Powell’s conclusion in McClesky could also be applied to Alexander’s book: that her “claim, taken to its logical conclusion, throws into serious question the principles that underlie our entire criminal justice system.”

Indeed it does.

Samuel K. Atchison has served as a welfare policy analyst, social services administrator, social policy consultant, and prison chaplain. He is the president of the Trenton Ecumenical Area Ministry and a community partnership manager with the Amachi Mentoring Coalition Project (AMCP), a program of the Philadelphia Leadership Foundation that provides mentoring to children impacted by incarceration.

One Response

Slavery wasn’t unconstitutional, until an amendment was added. If you find that your constitution is used to defend systemic oppression and crimes against humanity, then maybe it’s time for at least another amendment.