They were lynched. Mutilated. Dragged, dismembered, drowned. Strangled, stabbed, shot. They were beaten, burned, hanged. And they will not be forgotten.

Thanks to the vision, research, and hard work of the Equal Justice Initiative and its founder Bryan Stevenson, thousands of African American people whose lives were tragically ended as a result of racial terrorism will be remembered. On April 26, 2018, in Montgomery, Alabama, EJI opened the The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice (popularly called “the lynching memorial”).

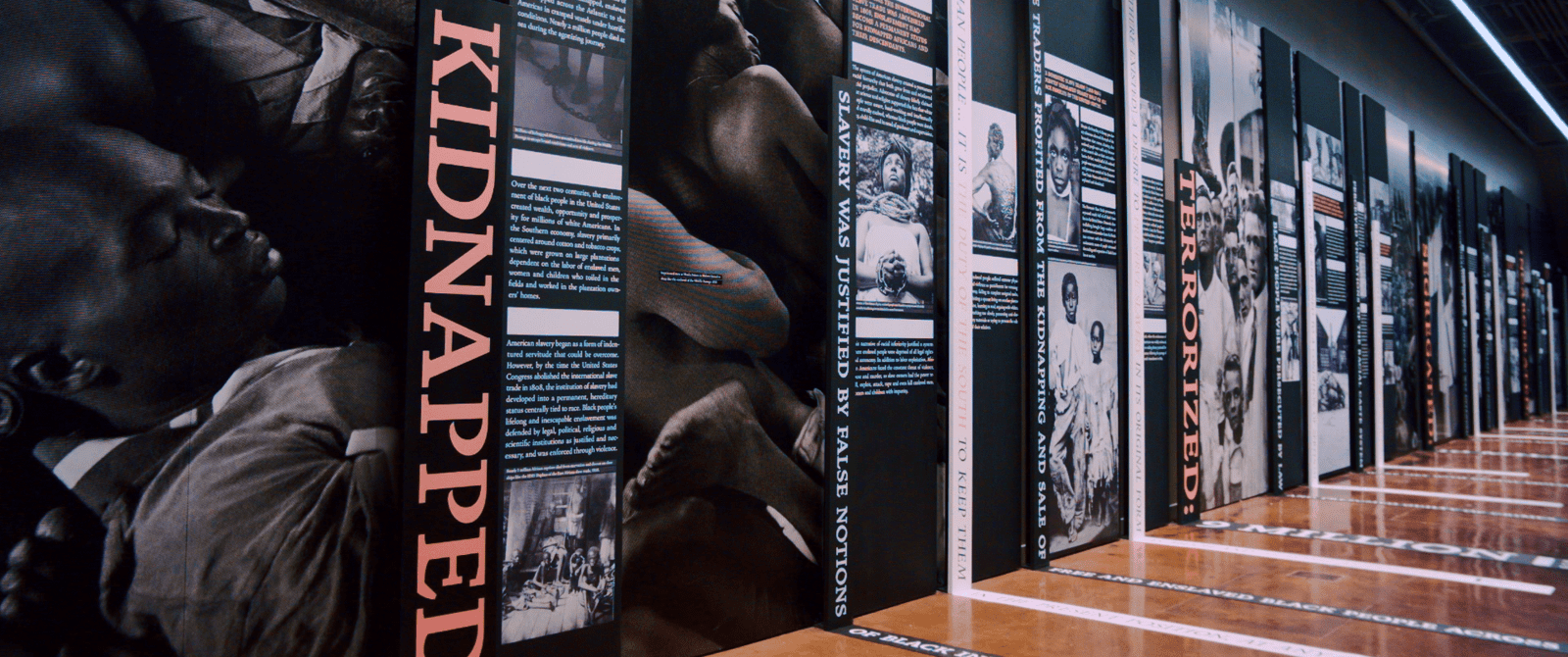

The museum is housed on the site of a former slave warehouse—within walking distance of both the Alabama River, where slave ships docked; and the former downtown auction block where black people were sold like property to the highest bidder. The museum chronicles the evolution of African American subjugation: the period of enslavement, post Civil War Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and on through the current crisis of intentional mass incarceration. A progression through the 11,000 square foot museum allows visitors to see how new methods of oppression are employed when others end.

The museum uses technology and interactive media to engage visitors. And it is engaging. But understand this: the experience is not comfortable, emotionally or cognitively. It is meant to challenge misconceptions, increase understanding, touch hearts, and ultimately move toward healing.

The experience is not comfortable, emotionally or cognitively. It is meant to challenge misconceptions, increase understanding, touch hearts, and ultimately move toward healing.

Less than a mile away from the museum is the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which honors the lives of more than 4,400 African Americans murdered between 1877 and 1950 as a result of racial terrorism. It memorializes black lives that otherwise would be erased. It demands respect for their humanity. And it gives voice to all who were silenced: Remember me. See my name. I was someone’s father, mother, child, friend. I was a person like you. I was hated. I was hunted. I was terrorized. I was killed.

The prevalence of lynching is described by journalist and Pulitzer Prize-winning author, Isabel Wilkerson, in her book, The Warmth of Other Suns. Wilkerson writes that from 1889 to 1929, one person was hanged or burned alive every four days. At the memorial there are 800 hanging steel monuments, one for each U.S. county where a lynching occurred. Engraved on each one are the names of African Americans who were lynched in that place. According to Kiara Boone, Deputy Program Manager at Equal Justice Initiative, EJI staff researched each represented case of racial terror lynching, corroborating every incident with at least two independent sources.

Racial terror lynching was a form of entertainment. As conveyed by the late theologian James Cone in The Cross and the Lynching Tree, lynchings were a “public spectacle, often announced in advance in newspapers and over radios, attracting crowds of up to twenty thousand people.” Souvenir body parts were often in demand.

But more than just entertainment, lynching was foremost a form of oppression and social control. Lynching occurred in locations where legal systems for bringing lawbreakers to justice existed; these acts of terror were extralegal white mob violence designed to instill fear, reinforce segregation, and exalt the ideology of white supremacy. As governmental officials turned their heads the other way, Black persons were dragged from homes, roads, jails, and courthouses by mobs bent on enacting brutal executions. According to Adam Gussow, author of Seems Like Murder Here, Cole Blease, former U.S. Senator and Governor of South Carolina, said lynching was a “divine right of the Caucasian race to dispose of the offending blackamoor without the benefit of jury.”

This hostile and dangerous environment was responsible for the largest mass migration of African American people—nearly six million—in the 1900s, from the rural south to the urban north and subsequently other regions. They abandoned the confederate states as refugees from terror, although some lynchings also occurred in the north.

Placards displayed at the memorial tell individual stories:

- Henry Smith, 17, was lynched in Paris, Texas, in 1893 before a mob of 10,000 people.

- Harry Patterson was lynched in Labelle, Florida for asking a white woman for a drink of water.

- Arthur Jordan was lynched in Warrentton, Virginia for eloping with a white woman.

- Lacy Mitchell was lynched in Thomasville, Georgia for testifying against a white man accused of raping a black woman.

- Some lynching victims were targeted for their efforts to organize for political and economic equality.

During my time in Montgomery, I had both formal and informal conversations about the local response to the opening of The Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. Consider that these were erected in the city of Montgomery—a former capital of the Confederacy—and where confederate monuments and markers abound. Consider that these exist in a place that was resistant to the display of any markers in memory of the enslaved people who were trafficked there. Consider that these now stand in the State of Alabama, where Confederate President Jefferson Davis has a holiday, as does General Robert E. Lee (shared with MLK Day).

Of course, Montgomery is also the birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement, traced to the moment when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus. Unsurprisingly, though, there was some initial resistance to the Legacy Museum. It is difficult for people to face the reality of such horrific acts of cruelty, and worse to face one’s own apathy regarding the suffering of others. But progress is already being made. In fact, the editorial board of one 200-year-old local newspaper, the Montgomery Advertiser, expressed remorse for the ways it had been “careless in how it covered mob violence and the terror foisted upon African-Americans from Reconstruction through the 1950s.” The Montgomery Advertiser partnered with EJI to run a series of stories called “Legacy of Lynchings: America’s Shameful History of Racial Terror” in conjunction with the museum’s opening.

Contemplate what it must have been like to live daily under the constant threat of violence. To be subjected to a legal system that offered no justice for assaults on black bodies. To be tortured and killed for daring to assert one’s humanity. The various exhibits allow visitors to explore the answers to such questions. The memorial sits on a beautiful six acre park, with spaces carved out for intentional visitor reflection.

Confronting the truth of America’s legacy of racial terror is a requisite step forward in the process of healing and racial reconciliation.Click To Tweet

Confronting the truth of America’s legacy of racial terror is a requisite step forward in the process of healing and racial reconciliation. The Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice are sacred spaces, truth telling spaces. Introspective spaces. All people, regardless of race, ought to visit. Take a friend. And then linger in the space for a while. Sit by the massive water feature, as I did, and process the experience. Acknowledge some of the worst atrocities in American history, reflect on its impact on the descendants of victims and offenders, consider the residual effect on Americans. And then, begin to envision a healthy way forward.

Kimberlee A. Johnson is a faculty member and Director of Urban Studies at Eastern University, and is Founder / Overseer of Fellowship of Women Clergy.