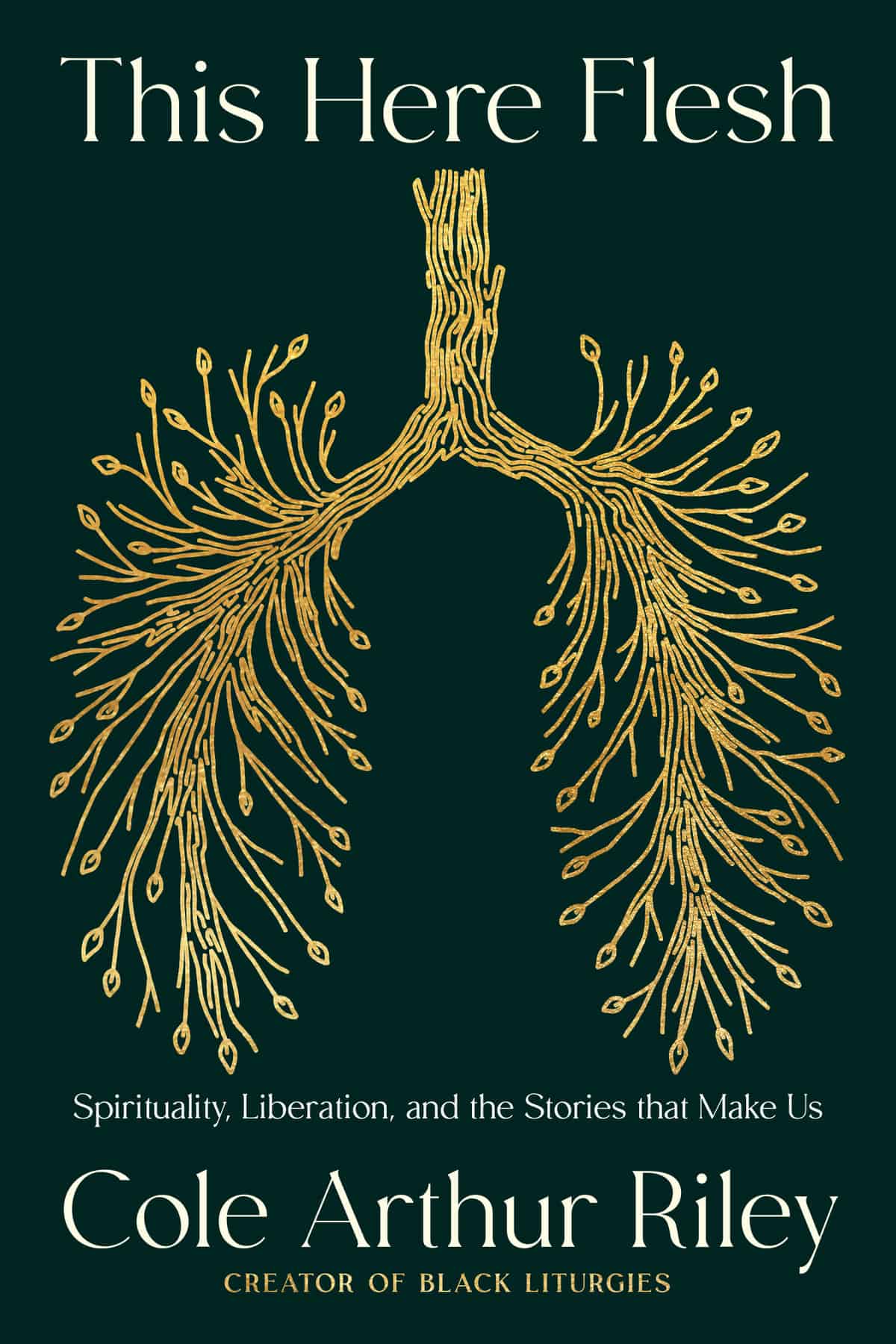

This month, we are introducing you to some incredible Black authors and thinkers who are helping us find a pathway to sustainable peace-building, ongoing reconciliation, and honest reflection. Today we talk with Cole Arthur Riley, creator of Black Liturgies, a space for Black spiritual words of liberation, lament, rage, and rest; and a project of The Center for Dignity and Contemplation, where she serves as Executive Curator. Her new book, This Here Flesh: Spirituality, Liberation, and the Stories That Make Us, is published by Convergent Books, a division of Penguin Random House.

This month, we are introducing you to some incredible Black authors and thinkers who are helping us find a pathway to sustainable peace-building, ongoing reconciliation, and honest reflection. Today we talk with Cole Arthur Riley, creator of Black Liturgies, a space for Black spiritual words of liberation, lament, rage, and rest; and a project of The Center for Dignity and Contemplation, where she serves as Executive Curator. Her new book, This Here Flesh: Spirituality, Liberation, and the Stories That Make Us, is published by Convergent Books, a division of Penguin Random House.

Why did you title your book This Here Flesh?

The title comes from a scene in Toni Morrison’s Beloved. In the book, there’s this place they call The Clearing, where the matriarch, Baby Suggs, gathers all her people for a holy meeting. First, she leads them in this embodied, emotional spiritual experience, asking the men and the women and the children to laugh, and dance, and cry. And then eventually, they all collapse in the grass together and listen to her sermon, which starts, “In this here place, we flesh. Flesh that weeps laughs, flesh that dances on bare feet in grass—love it.” And then she goes on to give a message on the power of honoring the physical.

The title comes from a scene in Toni Morrison’s Beloved. In the book, there’s this place they call The Clearing, where the matriarch, Baby Suggs, gathers all her people for a holy meeting. First, she leads them in this embodied, emotional spiritual experience, asking the men and the women and the children to laugh, and dance, and cry. And then eventually, they all collapse in the grass together and listen to her sermon, which starts, “In this here place, we flesh. Flesh that weeps laughs, flesh that dances on bare feet in grass—love it.” And then she goes on to give a message on the power of honoring the physical.

When I think of the kind of spirituality I wanted to engage in my book, I knew it would be that of The Clearing. A spirituality that is embodied, emotional, intergenerational—and, of course, grounded in liberation. As I wrote, I noticed parallels unfolding between the role of the home and the hauntings of the past, and the role of home in the intergenerational stories I was engaging. The book dedication reads: “To the house on cemetery lane: we’re not afraid of you.”

Which is a complicated dedication, really. What does it mean to remember well, the haunts and the beauty?

How do the stories we’ve experienced affect our ability to see the beauty and hope around us? How can we become people who can dream and believe there is a bright tomorrow?

I’m not sure that is necessarily the purpose of dreaming—to believe in a “bright” tomorrow. I’m much more interested in simply being able to believe in tomorrow (whatever that may be). To have an imagination for going on. Hope is not always triumphant.

But I do think being grounded in the stories that have formed helps with hope. Helps with perceiving beauty even. When you practice remembrance—nuanced and truthful remembrance—you’re traveling into stories and reminding yourself what it looks like to go on. You’re remembering the terrors, but also the beautiful. Well, good storytelling does that.

In the book, you talk about fear and write, “Fear becomes anxiety when it makes its home in you. Its chief attachment is not memory or villain or situation or future; its chief attachment and subject is you.” What has overcoming fear looked like to you, and how can fear be a teacher to all of us?

I’ve always been a very scared person. For as long as I can remember, really. I don’t think I’ve overcome it. In the book, I talk about “rising to meet it.” There’s something significant in that. To approach your fear and not suppress it—it makes space for you to really interrogate what is at risk, what your body is communicating, and to discern if the fear can be trusted or not.

I say this because fear can also be one of our fiercest protectors. A sacred intuition telling us that something just isn’t right. It is what keeps us from jumping from building to building, or touching the fire’s flame. There is something really nurturing in it, at times.

And still, there is a fear, like you’ve mentioned, that is an anxiety. A fear that latches on to you. It is not interested in meeting you; it wants to possess you. I think I’ve learned to try to tell the difference. Between a fear that possesses you, and a fear that is warning you. And if I discern the former, I try to ground myself in my body all the more. Pay attention to sensory experiences, and receive truth from outside of me, until I have ownership over myself again. Until I can trust myself again. Some days are easier than others.

You also write about joy, saying, “Joy, which once felt as frivolous as love to me, has become a central virtue in my spirituality.” Tell us what joy means to you and how we can capture that as a hope for 2022.

I was never very interested in the topic of love or joy. It felt too…happy, excitable. Too bright. And I just didn’t have access to that. But I’m coming to understand joy in more nuanced ways. They say joy is in relationship with your parasympathetic nervous system—which is responsible for a calmness, a rested state.

I started to think of joy as not so much an energetic affect, but a resting space. A place of calm and contentment. It was much easier to access. In this season, I am rarely happy, but I always have a portal to joy. It looks like resting, slowing, connecting with myself.

Where are we at in this moment when it comes to conversations on racial divisions? How do we press into meaningful dialogue instead of running away when it gets difficult?

This is an interesting question. I don’t know. Maybe because the answer changes depending on who we mean by “we.” But I’ll say this, there’s this wonderful quote from Cherríe L. Moraga, who says, “The real power, as you and I well know, is collective. I can’t afford to be afraid of you, nor you of me. If it takes head-on collisions, let’s do it: this polite timidity is killing us.”

I love this call to collision. Sacred collision. It doesn’t mean you can’t walk away when the moment calls for it, but there are times where we must remain. And this doesn’t mean we do so by diluting our passion or demands. Anger, I think, is an inherently connecting force. Apathy steps away, looks away. Anger comes for you. It is always a moving toward something (for better or worse). And so, if we want dialogue, if we want folks to remain, we have to allow for that dialogue to be embodied, emotional, true.

And still, there are times, like I’ve said, where walking away is a sacred wisdom. These conversations are costly. There’s a toll on the Black body that I’m not quick to dismiss. So, I have a lot of respect and compassion on oppressed people who in the end choose the door. Follow the sound of freedom.