The Struggle with Tokenism

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published Novemeber 8, 2017. We’re re-posting in honor of Asian-American & Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

“Tokenism does not change stereotypes of social systems but works to preserve them, since it dulls the revolutionary impulse.” Mary Daly, radical feminist philosopher and theologian

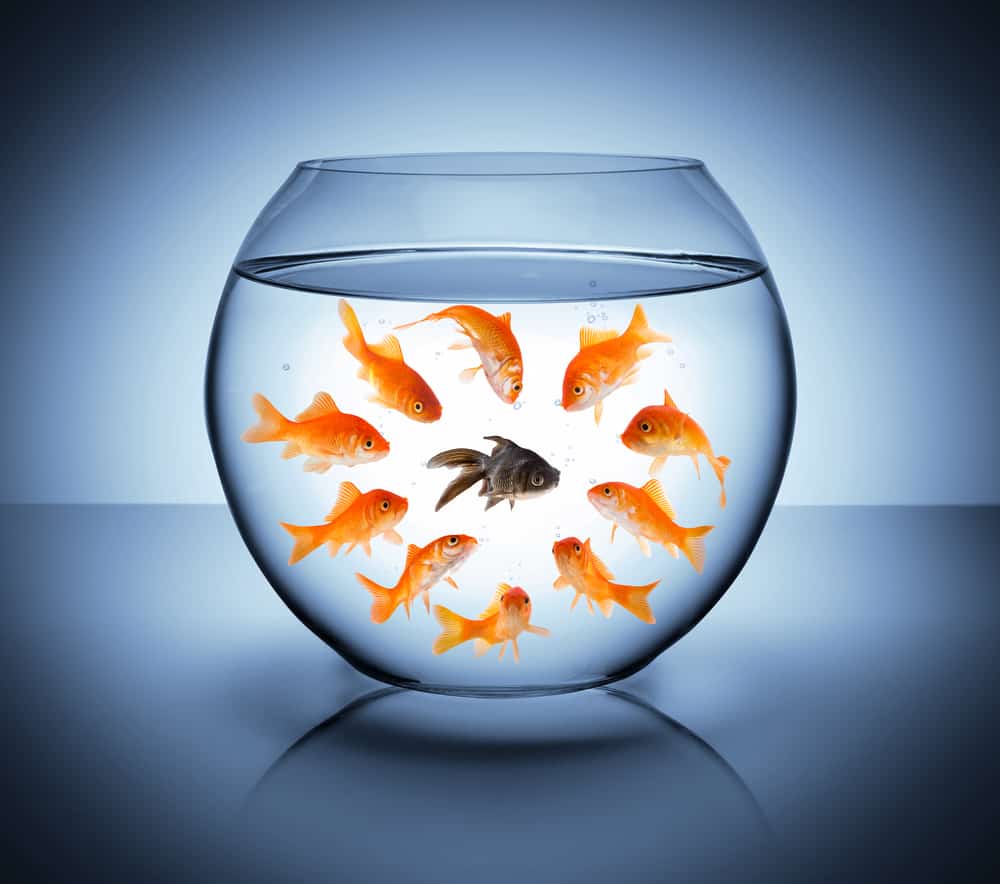

I am the only one.

On most committees or organizations, I am usually the only one. The only woman. The only young person. The only racial “minority.” And most recently, the only mother with young children. It was something I grew accustomed to rather quickly, this being the token fill-in-the-blank.

Growing up in suburban, white neighborhoods and attending equally homogenous schools, I was used to being different. Some days I enjoyed being distinct from others. I loved seeing friends experience Korean cuisine for the first time when they came over to my house, or their interest and delight when I managed to supply a few Korean words upon request for translation of any English word, or when they met my “cute” parents (because they were so tiny and novel).

Of course, later I would see how incredibly offensive all of this was, not only to me but also to my family. My parents hated hearing that my friends thought they were “cute,” as though they were toys. Sometimes my being the only one, or being different, was a way for those with any power or agency to keep those like me strangely dependent on them, whether for affirmation or validation. It took me a long time to see this power dynamic. Even though my parents would tell me over and over, “Be different,” I started to see this as confusing and mostly negative advice.

But being the only one has its advantages, too. Sometimes being the only one means more resources. Sometimes being the only one means being a spokesperson and having a monopoly on a discussion. Sometimes being the only one means people look to you automatically to be the embodiment or giver of insight into something specific.

My denomination has something called the Committee on Representation, which at various levels works to ensure an equitable representation (according to clergy and layperson, race, gender) in all the groups and bodies within the church. This includes everything from the local church governing board to committees at the national church level. I had never given it much thought until a close friend and colleague shared some of her experience chairing the committee in her geographical area. She joked that it was an “easy gig,” that meetings were usually held by phone or email, and that the bulk of the work mostly required vocal accountability.

There is a strange tension. On the one hand, it is wonderful that there exists a structure that is intentional about helping us maintain a level playing field when it comes to voices, and more importantly, votes. I think such a level playing field is not only an institutional necessity for decision-making and development but also an institutional expression of power and agency. Because we have been entrenched in inequalities for so long, it makes sense to have a plan where this is addressed over and over until it becomes a part of our social consciousness—so that in the future, we will not need a committee to help us with diversity. No doubt, it remains imperative that we continue to raise awareness about inequities and privilege, and to be a voice for the voiceless, and to close the gap between those on the center and on the periphery.

On the other hand, there is a tendency toward tokenism in such efforts. The easy gig, meaning, the easily dismissible task that is so easy it can be done over the phone or through periodic email exchanges, of any committee on representation means that we look for the surface qualities of people, as if these were what we want present in these leadership groups. It is sometimes a soft solution to our discomfort with these inequalities.

Yet, there is clearly a backlash to institutionalizing cultural diversity. In my ministry journey, I have worked in both Anglo and Korean churches, and in both communities, there are always huge differences based on both race and gender.

Affirmative Action: Focus on Numbers

“If you don’t like affirmative action, what is your plan to guarantee a level playing field of opportunity?” Maynard Jackson, politician

I often wondered if the Committee on Representation is our denomination’s version of affirmative action.

According to Frank Wu, a law professor at Howard University, though affirmative action is not a perfect solution, the intention behind it is equality and integration. The hope is to begin to counter the disequilibrium that has occurred for hundreds of years in this society, mostly in those spheres of life that are affected by class and economic status, race and culture, and gender, among many issues. In his book, Yellow: Race in American Beyond Black and White, Wu writes, “Affirmative action is the applied component of the commitment to work toward achieving a society that not only happens to be racially diverse but also strives to be egalitarian and inclusive.”

I appreciate the opportunities given to me that were most likely the result of affirmative action efforts, ones that I believe I would not have experienced or acquired because my ability or talent might have been downplayed because, plain and simple, I am a minority. Perhaps there were no minorities in that position previous to my inquiry, or there were no women who served in that particular capacity. Whatever the reason, whether a lack of history or lack of imagination, without affirmative action, I would not have as much of a chance as others. It took me a long time to admit that reality. I always upheld the American ideal of equal opportunity for anyone and everyone. But, like any ideal, what occurred was often very different from the dream.

And so the affirmative action effort by my denomination has helped to initiate awareness. Often women of color experience what I call a double silence. It is not only one’s skin color or ethnicity but also gender that doubly binds us up and causes us to be invisible to the wider culture. But with affirmative action we are a much more visible demographic in many spheres of work and life. People are becoming more aware of the talents and abilities of those who are normally underrepresented whether in colleges or in church communities.

“Only [the one] who can see the invisible can do the impossible.” Frank L. Gaines, former mayor of Berkeley, California

Awareness is essential, and is a helpful starting point. But what is also necessary beyond simply seeing is dialogue. The interfacing, interaction, and connection between people, particularly those who are in the center and those on the periphery, are transformative, not only for individuals but also for whole communities. Programs such as anti-racism training workshops are important steps toward conversations that are not easy or natural but that need to happen in order for real change to occur at institutional levels.

I had never felt comfortable talking about my race and ethnicity. As a Korean American I was always taught not to rock the boat. It was all about keeping my head down, nose to the grind, and working as hard as possible—this was the secret to success and having everything turn out fine. But it did not all turn out fine. I saw so many inequities all around me—from the lack of women in leadership in my home church, to never seeing a woman preach from the pulpit until I went away to college and visited my father, who was attending seminary at the time. I could not remove myself from those conversations about race and gender any longer if I were truly to be faithful to God.

A dear friend was part of a group who started the first anti-racism training at the seminary. I was inspired by the experience but also saddened by the scarcity of non-minorities present. I later heard many of the few nonminority attendees say somewhat condescending and disparaging things about the purpose for and necessity of the training. I was shocked. Speechless. I could not believe that these people would be my colleagues in ministry someday. How could we possibly bring God’s kingdom to bear in the world when we could hardly manage it in our own student community?

There is so much work to be done. It is not an easy issue, and there is definitely so much more that complicates it.

Authentic alliance: focus on network

“Cooperation is the thorough conviction that nobody can get there unless everybody gets there.” Virginia Burden Tower, The Process of Intuition

While I cannot downplay the importance of regulating diversity, I also cannot help but ask if we too easily dismiss what it means that we continue to need such a committee in the first place, especially in our supposed post-feminist and post-racist society? As briefly mentioned above, the other side of affirmative action is the tendency toward tokenism. Perhaps part backlash and part natural consequence, I would often find myself the token, like a good placeholder in those endeavors for diversity, more like a trophy or medal that expressed whatever group was now truly progressive and therefore sensitive to the plight of silenced minority cultures and groups in society. But my ability or talent, my perspective, and my voice were downplayed in so many ways because they were not deemed necessary. My being Asian or a woman or young was good enough.

Though I appreciated the opportunity for a place at the table, it often felt forced and awkward. And I hardly ever spoke up. I did not think it was important for me to say anything, and mostly I felt my being there was a formality—no one could possibly care about my opinion or perspective. I approached meetings with a dread because they were vocational obligations, and so I always looked forward to the end, whether of the meeting or the term. But after the first few years of my journey as an ordained minister, my husband encouraged me to see them as learning opportunities, as well as a chance to offer something new and unexpected. He reminded me that the church needs my voice, and for me to exhibit God’s faithfulness, it would mean stepping out of the boat even if I did not necessarily want to rock it.

I had a hard time living into this role. I often vacillated between both extremes. Sometimes, it felt presumed that I would need to assimilate into the local culture in order to be heard or understood by the committee of even my own congregation members. So, I tried to adopt the voice, mannerisms, and authority of the other members on the committee. Of course, that did not work well for me. I felt even more self-conscious and wondered if I would seem like a fraud. When I went the other direction and tried to speak up honestly, sometimes it felt that what I was saying was completely radical. I wondered if others thought I was a raging liberal. Even if another committee member would say something similar, it seemed to find better reception. I cannot help but think that this happened not because of the message but because of the messenger.

One of my favorite novels, East of Eden by John Steinbeck, speaks of this phenomenon. There’s a telling scene between Samuel and Lee, the Chinese servant who is with the family, about Lee’s (exaggerated) Chinese accent:

Lee looked at him and the brown eyes under their rounded upper lids seemed to open and deepen until they weren’t foreign any more, but man’s eyes, warm with understanding. Lee chuckled. “It’s more than a convenience,” he said. “It’s even more than self-protection. Mostly we have to use it to be understood at all.”

Samuel showed no sign of having observed any change. “I can understand the first two,” he said thoughtfully, “but the third escapes me.”

Lee said, “I know it’s hard to believe, but it has happened so often to me and to my friends that we take it for granted. If I should go up to a lady or a gentleman, for instance, and speak as I am doing now, I wouldn’t be understood.”

“Why not?”

“Pidgin they expect, and pidgin they’ll listen to. But English from me they don’t listen to, and so they don’t understand it.”

“Can that be possible? How do I understand you?”

“That’s why I’m talking to you. You are one of the rare people who can separate your observation from your preconception. You see what is, where most people see what they expect.”

The authentic connection between Samuel and Lee is one that exhibits God’s kingdom to me. To truly see what is, rather than what is expected or falls under certain stereotypes and categories, and then to affirm, encourage, and make space. Affirmative action was never meant to be a permanent solution because it too easily turns into a diluted form of community where tokenism is the adhesive. But the existence of real network, where the focus is not on numbers or statistics and where people are truly tied up together in all the messes and complications, this is God’s kingdom of radical existence rooted in love and grace.

This was something impressed upon me recently in ministry, and particularly in my life as a clergywoman of color. We need each other’s voices. We do not need numbers. We do not need quotas. We do not even need goals or standards. We need each other. We need each other’s experiences. We need each other’s dreams. We need each other’s stories. The kingdom of God is not a formula, it is not a committee, and it certainly is not meant to even look utopic and perfect. It is beautifully chaotic and interesting, and meant to be rich and full. And that means that I have to fully be myself wherever I am, no matter how hard or strange, no matter who can see or hear me.

“In dealing honestly with the problem of difference and the dream of pluralist feminism, I trust that we can be together where the Holy Spirit, our Divine Wisdom, our Sancta Sophia is both Hostess and Guest. With this hope I advocate the vision and the perspective which encompasses our coming to believe in the possibility of a variety of experiences, a variety of ways of understanding the world, a variety of frameworks of operation, without imposing consciously or unconsciously a notion of the norm.” Toinette M. Eugene, in Feminist Theological Ethics: A Reader

Mihee Kim-Kort is a Presbyterian minister, agitator, speaker, writer, and slinger of hopeful stories about faith and church. Her writing and commentary can be found at TIME, USA Today, Huffington Post, Christian Century, On Being, Sojourners, and Faith and Leadership. She is a PhD student in Religious Studies at Indiana University where she and her Presbyterian minister-spouse live with their three kids in Hoosier country. This article was excerpted from Streams Run Uphill: Conversations with Young Clergywomen of Color by Mihee Kim-Kort, copyright © 2014 by Judson Press. Used by permission of Judson Press.