In some ways, Auggie Pullman is just like any other fifth-grade boy. He loves Star Wars. He rides his bike. He plays XBox.

In some ways, Auggie Pullman is just like any other fifth-grade boy. He loves Star Wars. He rides his bike. He plays XBox.

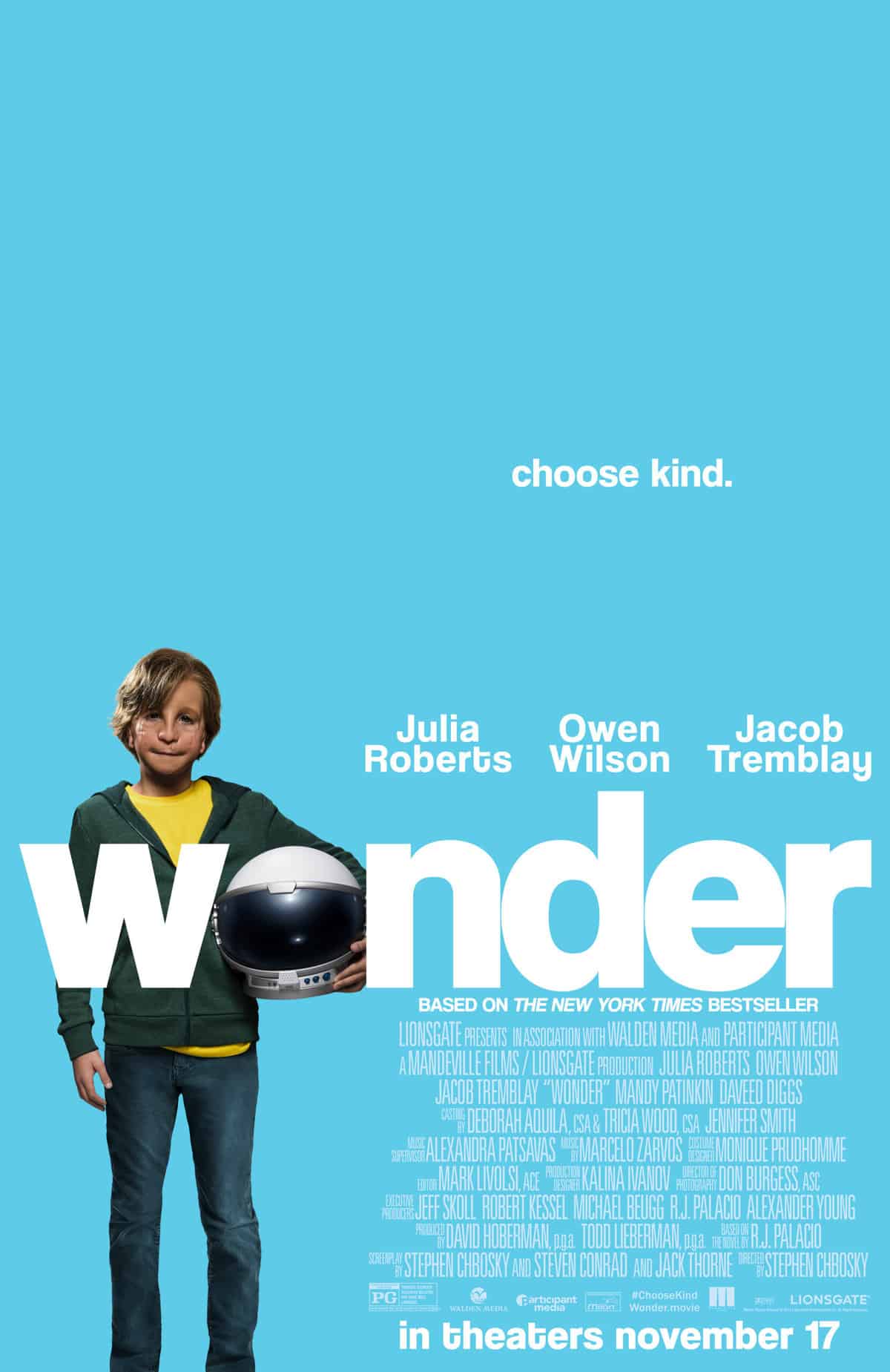

But in other ways, Auggie—the main protagonist of R.J. Palacio’s novel Wonder, and now the movie of the same name—is different. This difference isn’t hidden; it’s the first thing people see when they look at him. Because Auggie has facial differences, which is another way of saying “facial deformities.” Auggie’s had twenty-seven surgeries in his short lifetime, but the results have still left him far from looking ordinary.

“I feel ordinary inside,” Auggie (played by Jacob Trembley) says. “But I know ordinary kids don’t make other ordinary kids run away screaming in playgrounds. I know ordinary kids don’t get stared at wherever they go.”

In Wonder, viewers follow Auggie as he enrolls in a mainstream school for the first time in his life. All of the first-day-of-a-new-school jitters are here: will people like me? Will I like all my classes? Will I fit in? Except for Auggie, these fears are magnified multifold, because Auggie wears his differences in his very skin. Auggie is never going to blend in.

Watching their son walk toward the school building on his first day, Auggie’s parents (played by Julia Roberts and Owen Wilson) hold on to each other, emotions writ large on their faces. Then his mother prays: “Dear God, please make them be nice to him.”

I don’t know what it’s like to raise a child with visible disabilities, but I resonate with Auggie’s mother’s prayer. In my world, disabilities are hidden. In my world, children look like they might be able to blend in—but they never can. And so I pray for everyone who interacts with my family: “Dear God, please make them be nice.”

I’m always looking for touchpoints with my children to talk about how we understand and embrace difference. How would we treat someone like Auggie, if he enrolled in one of our schools? We all want to think we’d be the person who goes over and says hello…but would that be hard? Sometimes it’s a lot easier to watch someone do the right thing in a book or a movie than it is to do the right thing in real life.

Sometimes it’s a lot easier to watch someone do the right thing in a book or a movie than it is to do the right thing in real life.

One of the most poignant moments in the movie is when Jack, a true friend Auggie has made at his new school, is seen talking about Auggie when he doesn’t know Auggie is listening. And Jack says terrible things about Auggie, things that rupture their friendship and leave Auggie reeling. The film never satisfactorily answers the question of why Jack said the things he said, and the emotional resonance is stronger for leaving the question unanswered.

Because obviously, good people doing bad things is not a new phenomenon. Like Jack, most of us genuinely want to do the right thing, at least most of the time. But sometimes, we don’t do the right thing. As the Apostle Paul lamented, “I do not understand what I do. For what I want to do I do not do, but what I hate I do.” (Romans 7:15)

The genius of Wonder is that it doesn’t shirk away from the hard work of embracing difference. The characters are nuanced—the “good guys” lie, occasionally cheat, and even a very best friend can say incredibly hurtful things. In the movie, as in real life, forgiveness (and deeper friendships) come when we can acknowledge our failures and, together, try to do better. The first step toward acceptance is awareness: both of others, and of ourselves. And Wonder is awareness made beautiful.

Wonder is awareness made beautiful.

“Auggie Pullman can’t change the way he looks,” says school principal Mr. Tushman (played by Mandy Patinkin—and yes, Tushman—this is a movie about fifth-grade boys). “But maybe we can change how we see.” Through Wonder, we see with new eyes. And what we see is beautiful.

Editor’s Note: Wonder releases Friday, November 17th in theaters everywhere.

To learn more about real-life children living with craniofacial differences, watch the Children’s Craniofacial Association’s video of dozens of young people saying “I am Auggie Pullman!”

Elrena Evans is Editor and Content Strategist for Christians for Social Action. She holds an MFA in creative writing from Penn State, and has also worked for Christianity Today and American Bible Society. She is the author of a short story collection, This Crowded Night, and co-author of the essay collection Mama, PhD: Women Write About Motherhood and Academic Life. She enjoys spending time with her family, dancing, and making spreadsheets.