The Rise of the New Copernicans

Life is spherical. It is lived in 3D. It is better understood from lived experience than from abstractions. It is messy, provisional, and intrinsically relational. These are the guiding insights of millennials, the emerging American generation born after 1980. They tend to see their parents as flat earthers. They are the New Copernicans. They represent a distinctly new frame on reality. The New Copernican thesis is that the millennial generation is the major carrier of a fundamental shift in the American social imaginary—the way ordinary people imagine their world. This new cultural narrative or social imaginary may completely reshape our understanding of human society.[1]

In the spring of 1543, astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus lay on his deathbed in Frombork, Poland. He was 71 years old. His followers brought straight from the press the first printed copy of his life’s work, On the Revolutions of Celestial Orbits. Copernicus died that same day.

His book launched the scientific revolution, but it didn’t produce a paradigm shift in thought until a century and a half later, when Isaac Newton published his Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy in 1687. Copernicus didn’t have a theory in mind when he postulated his view of planetary motion; rather he had a “flash of insight,” a new picture in mind.[2]

We are currently living in the pregnant pause between the flash of insight by New Copernicans and the thunder of adjusting to a 3D world and its emerging social reality. We can assume that this perspective is even now reshaping the dynamics of relationships, careers, science, politics, business, and religion.

This article will argue that millennials are the carriers, not the cause, of a fundamental and lasting shift in the social imaginary. This shift is a rejection of the Enlightenment and its habit of seeing reality through abstract binary categories: sacred vs. secular or left vs. right. Millennials assume the priority of experience over abstractions and consequently do not place their life experiences into clean categories or systems. Instead they embrace the cross-pressured nature of contemporary life embodying the experience of hyper-pluralism. They reject either/or categories in favor of both/and thinking. They are also decidedly post-secular, refusing to the accept a “world without windows.” This paper will begin to explain how this social imaginary came to be and what it means for human society.

Watch more videos about New Copernicans.

Researchers refer to those who reached adulthood around 2000 as millennials. They are one of the most studied and important generational cohorts in recent memory. At 24.7 percent of the U.S. population, they are 84.4 million strong and poised to overtake boomers in terms of sheer number by 2030. Millennials are now the largest consumer group in the United States, with purchasing power that will exceed boomers’ in 2016—currently approximately $1.3 trillion in direct spending. Compounding their influence, this generation will receive a trillion-dollar wealth transfer from boomers over the next twenty years. Because of this, they have been the subjects of extensive market research. The significance to the culture of their values and frame on reality cannot be overstated. Those companies that are able to authentically enter this emerging conversation will be poised for significant success in the coming years.[3] Millennials are ignored at our own peril.

Maligned and misunderstood

As important and oft studied as millennials are, they are also consistently maligned and largely misunderstood. The popular press has criticized this emerging generation of young people as being too narcissistic, too lazy, too individualistic, and too plugged into technology. This negative take is unfortunate as it serves to keep boomers unaware of millennials’ distinct and valuable perspective. It is now time for the parent to listen to the child. It is our contention that the cultural sentiments expressed by millennials are a more accurate assessment of human nature and reality than that held by the previous generation. Their views are a corrective to the matrix of the Enlightenment and are a welcome corrective to its abstracting tendencies. Consequently, millennials are to be celebrated, not criticized.

It is also our contention that much of the research conducted on millennials is simply wrong, as the research has been framed incorrectly. Too often, millennials are viewed through a distorting lens.

Why this is the case is complex. But if one tells a story about a group and they cannot see themselves in your story and worse are angered and alienated by the story you are telling about them, then perhaps there is something wrong with the story itself. Something is off in most millennial research.

Here are some suggestions as to why this is the case. Research has been framed in categories rejected by millennials. Albert Einstein noted, “You can’t solve a problem within the same frame that created it.”[4] Thus you cannot analyze a protesting perspective to the Enlightenment with the tools of the Enlightenment—not without great care and sensitivity anyway. One cannot comprehend a 3D reality within a 2D frame, as Edwin A. Abbott depicted in his 1884 novella, Flatland (Dover, 1992). So there are evident methodological difficulties in millennial research.

Next is the problem of analyzing shifts in perspective. Survey research takes snap shots of what is a dynamic and fluid process. Big data, or predictive analytics, is effective in making assumptions within a given frame, but it is far less effective in identifying shifts between two frames. The New Copernicans represent a frame shift. Kate Crawford, principle researcher at Microsoft Research, writes in the Harvard Business Review: “Data and data sets are not objective; they are creations of human design. We give numbers their voice, draw inferences from them, and define their meaning through our interpretations. Hidden biases in both the collection and analysis stages present considerable risks and are as important to the big-data equation as the numbers themselves.”[5] Lisa Gitelman in Raw Data Is an Oxymoron adds,

At a certain level the collection and management of data may be said to presuppose interpretation…. Objectivity is situated and historically specific; it comes from somewhere and is the result of ongoing changes to the conditions of inquiry, conditions that are at once material, social, and ethical…. Data too needs to be understood as framed and framing, understood, that is, according to the uses to which they are and can be put.[6]

Big data should be thought of as a Top Fuel dragster, effective in going extremely fast in a straight line but far less effective on a winding alpine road with repeated switchbacks. We believe that the error of past analysis of millennials has been in not allowing millennials themselves to establish the criteria for analysis or the questions for the survey. Researchers have assumed a frame of reference that does not authentically emerge from millennials but has been assumed of them by boomer social scientist researchers. Consequently, much is left out or distorted in the process.

Let us compare two ads that target millennials. The first is from State Farm. Like all insurance companies, State Farm sells risk abatement against an anticipated life trajectory. Their ad “Never” assumes an ongoing generational continuity between millennials and boomers, even if somewhat delayed. It illustrates the “maturational delay” explanation referred to by Pew researchers. The male character in the ad pronounces, “I’m never getting married. I’m never having children. I’m never moving to the suburbs. I’m never going to drive a minivan. I’m never having more children…,” while going on to do precisely those things. This ad is based on the faulty assumption that millennials will eventually age to look just like their parents, that what is at play in their distinctiveness is nothing more than maturational delay. This is an analysis that favors the status quo. It assumes that millennials will resort back to the older frame as they age, when in fact this is highly unlikely. This ad was clearly not written by millennials, as it avoids considering millennials as representing a fundamental and lasting frame shift.

The second ad is from Lincoln MKC, Ford Motor Company’s luxury brand, and features millennial actor Matthew McConaughey. Developed by the New York ad agency Hudson Rouge, it successfully captures millennials’ high regard for authenticity and expressive individualism. International Business Times writes, “Lincoln, according to AdAge, has contracted McConaughey to win a ‘younger, more progressive’ consumer. The TV ad you’ve probably seen by now is just the beginning: The deal is multiyear and will include digital spots created by Danish director Nicolas Winding Refn that attempt to get viewers to experience the MKC through ‘unscripted moments’ with McConaughey.”[7] Sales for Lincoln have risen 25 percent since the ad series began. The grounding rationale for life’s choices according to this ad is simply “I just liked it.” This agency understands millennials. Careful analysis can save companies from missing the mark with this substantial, hype-proof, media-savvy, brand-defining audience.

Finally, we need to acknowledge the difficulties of generational cohort research. Our New Copernican thesis is not based on cohort effect research. A cohort is an aggregate of individuals within a given population who experience the same event(s) within the same time interval. Cohort research assumes that a defined generation with common life experiences will give rise to distinctive values, attitudes, and behaviors.

Cohort research is most useful in medical epidemiology when the variables of the sample can be controlled. When cohort research is applied to wider social descriptions, as is typical in marketing and business, too many variables come into play to derive meaningful conclusions. It is difficult to disaggregate age, cohort, and period effects. In addition, no agreed upon scientific means to determine when one generational cohort ends and another begins, creating variability between cohort age markers by as much as ten years. As suggested above, this kind of research is used effectively in epidemiology and medical applications where the sample cohort is more defined, but it is less credible when it comes to defining social or cultural causation. Joseph Rentz and Fred Reynolds acknowledge, “Cohort analysis involves inferring effects from observable differences. The causes of the effects can only be decided on the basis of evidence outside the cohort table.”[8] The “why” to the observed effects cannot be determined from the analysis, because correlation is not causation. These research weaknesses are not often acknowledged in the sweeping generalizations being made about this or that cohort. Pop millennial research has been guilty of these weaknesses. Katina Sawyer, associate professor of psychology at Villanova University in Fast Company, “Because we don’t have longitudinal studies that tell us whether or not we are capturing age effects… or actual stable generational differences, generational research needs to be taken with a grain of salt given that we don’t have data that has followed older generations’ attitudes over time.”[9]

The New Copernican thesis is not positing that millennials are creating the New Copernican shift but rather they are the most prominent and visible carriers of this shift. In effect, they are the first ones up on the surfboard—thereby the most visible—but they cause neither the wave nor the rising tide.

In most cases, millennials only intuit the shift they embody but possess neither the language to express it nor the categories to understand it. They have a decidedly phenomenological and existential sensibility that is chronicled daily for all to see on Facebook and Instagram. Their mode of discovery is to start with lived experience. Rather than talk about ideological categories or theorize abstractly, they simply live it with their friends and muddle through. One of the aims of the New Copernican research is to provide language for this intuited shift.

This means that the New Copernican thesis is based on more substantial macro trends that exceed the millennial cohort effect. Thus the market and reach of this New Copernican shift is actually larger than 84.4 million millennials, and the changes represented are more enduring than can be explained away by age.

Shift in the social imaginary

The New Copernican thesis is that the millennial generation is the major carrier of a fundamental shift in the American social imaginary and that their leadership and influence in society will be substantial. We must grasp the significance of social imaginaries. Philosopher Charles Taylor explains:

By social imaginaries, I mean something much broader and deeper than intellectual schemes people may entertain when they think about social reality in a disengaged mode. I am thinking, rather, of the ways people imagine their social existence, how they fit together with others, how things go on between them and their fellows, the expectations that are normally met, and the deeper normative notions and images that underlie these expectations…. Because my focus is on ordinary people, this is often carried in images, stories, and legends.[10]

We are talking then about shifts in ordinary people’s unexamined expectations about life, and their unquestioned perceptions of reality. James K.A. Smith adds, “A social imaginary is not how we think about the world, but how we imagine the world before we ever think about it; hence the social imaginary is made up of the stuff that funds the imagination.”[11] Social imaginaries are not the same thing as worldviews, which tend to be more formal, academic, and cognitive. Social imaginaries are more likely to be the kind of assumptions found in pictures, stories, and songs, in advertising, film, and popular music. They reflect general assumptions about 1) What is the good life? 2) Who is a good person? and 3) How does one achieve both? Charles Taylor adds, “Every person, and every society, lives with or by some conception(s) of what human flourishing is: What constitutes a fulfilled life? What makes life really worth living? What would we most admire people for?”[12] The cultivation and curation of public social imaginaries is the primary work of storytelling cultural creatives.

We will return to the importance of story and storytelling in a moment. But before we completely dismiss the millennial cohort effect, we would be remiss if we did not note the significant list of events that took place during the formative years of this generational cohort. Here is a partial list. Any one of them is formative.

- Launch of the personal desktop computer – 1981

- Taskforce to Promote Self-Esteem and Personal and Social Responsibility – 1986

- Growth and acceptance of hooking up – 1990

- Introduction of digital cable television – 1990

- Launch of the Internet – 1991

- Attack on the World Trade Center – 2001

- Iraq War and the failure to find WMDs – 2003

- Launch of Facebook – 2004

- The first iPhone – 2007

- Wall Street financial collapse – 2008

- First Black U.S. president – 2009

- Birth of Black Lives Matter movement – 2013

- NSA and Wiki Leaks – 2013

- Same-sex marriage legalized – 2015

It does not take much imagination to see how in light of the collective impact of these culture-shaping technologies and events the millennial generation would be highly connected, self-absorbed, cynical of institutional authority, and acutely aware of hyper-pluralism and the contestability of belief. Entire books have been written on the social and cultural impact of the rise of the self-esteem movement, the iPhone, 9/11, the ubiquitous hook-up culture on college campuses, growing acceptance of sexual minorities and now same-sex marriage, and the global financial crisis with its impact on student debt.[13] Charles Taylor adds that in spite of our search for individual authenticity, we cannot deny that our choices are made against a given horizon. He writes, “It follows that one of the things we can’t do, if we are to define ourselves significantly, is suppress or deny the horizons against which things take on significance for us.”[14] Though different in content, these events and technologies are just as profound on the horizon of millennials as the experiences of the Great War and Depression were to their grandparents.

Frames, pictures, and stories

The importance of frames and framing is an essential part of the New Copernican thesis. Berkeley linguist George Lakoff observes that we think first in pictures or metaphors. C.S. Lewis concurs, “All our truth, or all but a few fragments, is won by metaphor.”[15] When the facts do not fit a frame, the facts bounce off and the frame remains. Facts and arguments work within a frame, but they are not effective in shifting a frame.[16] Frame shifts are the consequence of engaging the imagination, particularly through stories and pictures. One may use logic within frames but must use stories between them.

An examination of the social imaginary is a study of storytelling. Stories are tied to our intrinsic need for meaning, for making sense of the world. Nancy Duarte argues that stories and storytelling in the modern world is the surrogate language for religion. Alasdair MacIntyre adds in After Virtue (Notre Dame, 2007), “I can’t answer the question ‘What ought I do?’ until I first answer the question, ‘What story am I in?’”[17] Stories are how we make sense of the complexity of life.

The neuroscience of Iain McGilchrist reinforces this point. In his magisterial book, The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World (Yale, 2010), he argues that we must find ways to engage the right hemisphere of the brain—the part of the brain that sees broadly, finds patterns, and creates meaning. McGilchrist laments that the West has for too long biased reason and the left hemisphere of the brain, which examines things closely and analytically at the expense of the imagination. When the left-brain leads, it abandons the right and loses the ability to see reality as a whole. The emissary (the rational mind) usurps the master (the intuitive mind).

In Western philosophy for much of the last 2,000 years, the nature of reality has been treated in terms of dichotomies…. Philosophy is naturally given, therefore, to a left hemisphere version of the world, in which such divides, as that between the subject and the object seem especially problematic. But these dichotomies may depend on a certain, naturally dichotomizing, “either/or,” view of the world and may cease to be problematic in the world delivered by the right hemisphere, where what appears to the left hemisphere to be divided is unified, where concepts are not separated from experience, and where the grounding role of “betweenness” in constituting reality is apparent.[18]

McGilchrist concludes with Albert Einstein’s warning, “The intuitive mind is a sacred gift, and the rational mind is a faithful servant. We have created a society that honors the servant, but has forgotten the gift.”[19] New Copernicans get this, for it is this left-brain matrix they abandon. They have taken the red pill à la The Matrix, gone down the rabbit hole, and now see through the frame of pictures, the imagination, and stories. They embody a corrective to the biases and reductionism of the Enlightenment.[20]

For this reason storytelling cultural creatives are central to understanding the frame shift we are calling the rise of the New Copernicans. These opinion leaders—or, better, imagination curators—are most responsible for telling the public stories that give shape to the collective social imaginary. Cultural creatives are in the business of defining the unconscious assumptions about reality for most people.[21] To paraphrase University of Virginia sociologist James Hunter states, “The power of culture is measured by the extent to which its definition of reality is realized in society and reinforced by those institutions that shape the social imaginary.”[22] Tim Keller adds, “Culture changes when a society’s mind, heart, and imagination are captured by new ideas that are developed by thinkers, expounded in both scholarly and popular forms, depicted in innumerable works of art, and then lived out attractively by communities of people who are committed to them.”[23] The power storytelling cultural creatives wield creates reality or minimally curates the social imaginary. These influential storytellers can be found in many cultural fields and across numerous media platforms but are most commonly found in social media, advertising, elite media, television, and film.

Father Thomas Halik, Czech philosopher priest and 2014 Templeton Prize winner, has described the shift in social imaginary as the shift from settlers to seekers. New Copernicans represent seekers. Halik stated in the New York Times, “I think the crucial difference in the church today is not between so-called believers and nonbelievers, but between the dwellers and seekers.” Dwellers are those who are happy where they are, who feel they have found the truth, while seekers are still those looking for answers. Anyone can be an explorer: a Catholic, a Muslim, even an atheist. Halik believes that those in the community of seekers actually have more in common with each other than do seekers and settlers from within the same faith tradition.[24]

Millennials are the poster child of seekers because they hold an open mind, adopt a provisional attitude toward belief and reality, and long for more. They embrace epistemological humility (the starting attitude), follow the scientific method and the explorer’s quest (a process of open inquiry), and maintain a curious metaphysical openness to the laws of life wherever they may be found. They are opposed to what sociologist Peter Berger called “a world without windows.”[25] Their seeker perspective is open to the transcendent. They celebrate the journey, the exploration and the quest for new discoveries. They adopt the posture of a humble pilgrim or a courageous explorer rather than an arrogant teacher or know-it-all theologian.

Three kinds of secularity

The other way to get at this shift in social imaginaries is through Charles Taylor’s study of secularity found in his magnum opus, A Secular Age (Harvard, 2007). In this book he explores three uses of the word “secular”: secularism1, secularism2, and secularism3.

- Secularism1 – medieval, one-dimensional perspective (1D)

- Secularism2 – Enlightenment, two-dimensional perspective (2D)

- Secularism3 – contemporary, three-dimensional perspective (3D)[26]

What we are suggesting is that the New Copernican frame shift is the move from Secularism2 (Enlightenment) to Secularism3 (post-postmodern). In this view, all perspectives and institutions beholden to an Enlightenment-derived “either/or” perspective and its aspiration for cognitive certainty are both suspect and passé. This is especially true of American institutional evangelicalism.[27] Rather than thinking of a “secular” age (secularism3) as synonymous with unbelief, Taylor suggests that it is now best understood as different, contested ways of apprehending reality.[28]

In the medieval age, secularism1 refers to “worldly” vocations, as in farmers were secular and priests were religious. Secularism1 had to do with one’s position or status within a generally unified and transcendent understanding of society. The medieval use of “secular” did not have any negative religious connotation. Everyone assumed that they were living within a larger spiritual reality, under a spiritual canopy, in which they merely served different functions. Theirs was a unified, one-dimensional (1D) world.

This changed in early modernity and into the Enlightenment. During this period, the “secular” became what Taylor calls secularism2. Assuming that “secular” reason was unbiased, rational, and opposed to tradition (the ancien régime), secularism2 pitted reason against faith and science against religion. This either/or binary framing came to shape debates about science and religion.

It can be seen as recently as the public controversy surrounding the New Atheists. According to Taylor, the public hype of the New Atheism, with its two-dimensional (2D) framing, is increasingly out of touch with the dominant cultural trend. It is the afterglow sunset of a dying perspective rather than the dawn of a new era. Recently, New Atheist authors have turned to exploring a more open form of secularism—see Sam Harris’ Waking Up: A Guide to Spirituality without Religion (Simon & Schuster, 2014) and Philip Kitcher’s Life After Faith: The Case for Secular Humanism (Yale, 2014). The secularization story when presented as a “subtraction story”—“tales of enlightenment and progress and maturation that see the emergence of modernity and ‘the secular’ as shucking the detritus of belief and superstition”—is not correct, which opens the door to secularism3.[29]

What we experience in secularism3, rather than an antipathy toward unbelief, is a renewed openness and explosion of many modes of believing, all of which are contested and held with a more humble open hand. The either/or dichotomies of secularism2 are rejected for the both/and framing of secularism3. Seth Godin counsels, “In a world where nuance, uncertainty, and shades of grey are ever more common, becoming comfortable with ambiguity is one of the most valuable skills you can acquire. If you view your job as taking multiple choice tests, you will never be producing as much value as you are capable of…. Life is an essay, not a Scantron machine.”[30] So a secular3 age does not entail the rise of atheism and unbelief but instead the rise of cross-pressured belief, where belief and doubt are fused uncomfortably together. Philosopher James K.A. Smith explains: “The ‘salient feature of the modern cosmic imaginary’ or cultural narrative that Taylor highlights ‘is that it has opened space in which people can wander between and around all these options without having to land clearly and definitely in any one.”[31] Seekers, explorers, and pilgrims all. One hears this “sloppy” but deeply felt conjunction in the opening lines of Julian Barnes’ novel Nothing To Be Frightened Of: “I do not believe in God, but I miss him.”[32] It is also seen in Frank Schaeffer’s Why I Am an Atheist Who Believes in God.

We can also get at this by replacing religious belief with the subject of romantic longing in contemporary stories. This is creatively illustrated in the HBO TV show Girls. The show describes a confused and somewhat unsettled world where the cross-pressured nature of beliefs, relationships, and sexuality are depicted with authenticity and frankness. Girls writer, showrunner, and star Lena Dunham writes about her character, Hannah Horvath, at the raw intersection of her public and private life. Horvath’s is a portrait of a complex soul where longing and loss, self-love and self-loathing, aspirations for social justice and privilege bereft of higher purpose are woven together in a manic and medicated tapestry.[33] Dunham voices a 3D millennial sensibility. Her narrative tone is a paradigm shift away from the cheery adolescence of Friends or the upwardly mobile urbanism of Sex and the City. Her “comic” cultural narrative is messiness and ambiguity personified—where unemployment, STDs, gender confusion, and serial relational humiliation are de rigeur. Welcome to the cross-pressured authentic relational experience of millennials. This messiness is coupled with a ceaseless longing, the ongoing hope for something more. It is not the dead end of nihilism, but the valiant hope against hope for meaning and love. “A kiss may not be the truth, but it is what we wish was the truth,” states Steve Martin in L.A. Story. The kiss portends the reality of true love against all odds. In this context sex means little, the “L” word, i.e., love, a lot.

Those who live within secularism3 assume a secular frame, the absence of God or gods, but simultaneously have a nagging sense of incompleteness. They sense that their immanent frame is somehow haunted by a larger spiritual reality. Jewish psychiatrist Jeffrey Satinover writes, “Jung understood, as few of his contemporaries did—nor do many nowadays—that mere rationalism, tolerance, and humanism is no match for the awakened pagan soul.”[34] New Copernicans possess this awakened pagan soul, this expectant romanticism, this unquenchable religious longing. The consequence is something Taylor describes as the “nova effect,” an explosion of different options for belief and meaning—from vampires and zombie movies to bells-and-smells high-church rituals.[35]

The Burning Man Festival in the desert of Nevada becomes the aspirational cultural zeitgeist event—where pagan spirituality and sexuality mix with counter-cultural communal utopianism and expressive individualism for a week each summer. Black Rock City, Nevada—the pop-up city of Burning Man—is an experiential layover on the spiritual sojourn to the New Copernican Jerusalem.

The New Copernican thesis claims that the millennial generation is the first visible group of carriers of this post-Enlightenment and post-secular social imaginary. Because the New Copernican sensibility is the result of macro cultural and philosophical forces, rather than merely a cohort effect, the forces at work will be more permanent and have a market impact broader than the 84.4 million millennials.

2D vs. 3D social imaginary

We have claimed that much of the analysis of millennials has been biased by a 2D framing of reality that tends to distort the 3D lived experience of millennials. What is meant by this 2D to 3D shift?[36]

Since the rise of modernity, highlighted by the Enlightenment in the West, our arguments are inclined to adopt a binary either/or frame. Such dualistic framing is neat, clean, and often reductionistic. It suggests that the position an individual takes—whether A or B—is somehow not tainted or influenced by the opposing position. It infers that absolute certainty is possible and is usually offered with an air of hubris. This is only possible when one starts with abstractions.[37]

Lived experience is not so easily reduced to pure states, to A-vs.-B dichotomies. An uneasy and ever-changing mix of A and B characterize lived reality. The lines are blurred, the colors mixed, the motives conflicted. Lived reality is more 3D than 2D—more opaque angles than straightforward reasons, more picture than proposition, more poetry than prose, more Zen gardens than New York streets, more Steve Jobs than Bill Gates, more St. Patrick than St. Aquinas.

This is not to say that truth does not exist, only that it does not come as an unalloyed good within human experience. Pure truth is an abstraction, not a lived experience. It is to assume the posture of a god than accept the limitations of a creature.[38] Human knowledge is always alloyed—a composite of truth and falsehood, belief and doubt, confidence and uncertainty. It is phenomenologically derived. Human experience is intrinsically contingent. This insight is the starting point for millennial New Copernicans.

Philosophical postmodernism has exposed as fraudulent the overly confident, unduly abstract nature of Enlightenment thinking. Postmodernism asserts that all that we believe we must accept with a measure of humility, openness to correction, and willingness to see the same truth from a different angle.

At issue is not what we believe but how many angles inform our beliefs. It is in this sense, as Charles Taylor claims, that we are all secular now. We are all touched by an acute awareness of alternative positions to our own. The price of pluralism and hyper-modernity is an increased acceptance that all belief is an alloy—infused from its inception with contestability, never held in a pure state. Truth exists, but it’s not as clear or certain as some have assumed.

Those who believe in absolute truth sometimes find this admission to the limits of human knowledge hard to swallow. In “contingency,” they hear relativism. But Michael Polanyi, the polymath who explored how tacit values influence scientific discovery, and all who have acknowledged a 3D world after him do not necessarily embrace relativism.[39] Rather, they embrace the possibility that some of our angles on the truth are incomplete, inadequate, or just plain wrong. As the Apostle Paul reminds us, “we know in part.” This means that everyone brings something unique and valuable to the conversation; no one has a corner on truth; and no one should assume so.

Taylor and others have emphasized the “cross-pressured,” “contestable” nature of belief in the modern world. They acknowledge that this is a new and distinctive human experience. We might still speak of “God” and “faith,” but how we believe has changed.

Take sexuality, for example. One may believe that God made humankind, male and female, and accept a hetero-normative bias. But in the modern world, the experience of gender, sexual orientation, and marriage is more up for discussion than ever before. Binary categories are immediately rejected in favor of a fluid continuum. Even conservatives on this issue must begin to face the reality of intersex persons.[40] The acceptance and assertion of LGBTQ rights is a logical outgrowth of these wider cultural shifts in the social imaginary. That this is so should not be surprising. Such is the “contestable” nature of identify, belief, and life in modern experience.

A consequence of the collapse of the Enlightenment project is a wider recognition of the 3D nature of reality. With the insights of neuroscience, we’ve come to understand that the long assumed superiority of the left-brain has us seeing a 3D landscape as a 2D map. Neuroscientist Iain McGilchrist laments, “Philosophy in the West is essentially a left-hemisphere process. It is verbal and analytic, requiring abstracted, decontextualised, disembodied thinking, dealing in categories, concerning itself with the nature of the general rather than the particular, and adopting a sequential, linear approach to truth, building on the edifice of knowledge from the parts, brick by brick.”[41] Much is lost in translation. One can hear the grinding of gears and see the inevitable frustration as persons try to fit a 3D experience into a 2D frame. In the end, it cannot be done.

As an apprentices of Jesus who believe strongly in creation and the incarnation and the messiness it entails, we believe Christians should naturally gravitate to 3D lived existence over 2D abstract fabrications. Ours is an earthy faith that smells of the barn and manger. Sadly many in the church have historically aligned themselves with a sanitized Enlightenment’s 2D framing, which is now being rejected by New Copernicans. Instead, we would be wise to embrace complexity and contingency, humanness and fallibility, ambiguity and paradox. This means adopting a humble attitude. As Sir John Templeton admonished, “Inherent in humility resides an open and receptive mind. We don’t know all the answers to life, and sometimes not even the right questions have been revealed to us.”[42] What is, however, being revealed to us is in the millennial generation are people who abandon 2D framing. And we have much to learn from them and much to celebrate. In spite of their awakened pagan soul and aimless spiritual wanderings, their instinctive intuitions are the hope of the church. Millennials long for a 3D spirituality—for a dirt-under-the-fingernails, humane spirituality. In this regard, we may have a lot to learn from Saint Patrick and Celtic Christianity, who offered the Celtic pagans of Scotland, Wales, and Ireland a spirituality where the dominant religious symbols were circles rather than squares.[43]

Four takes on reality

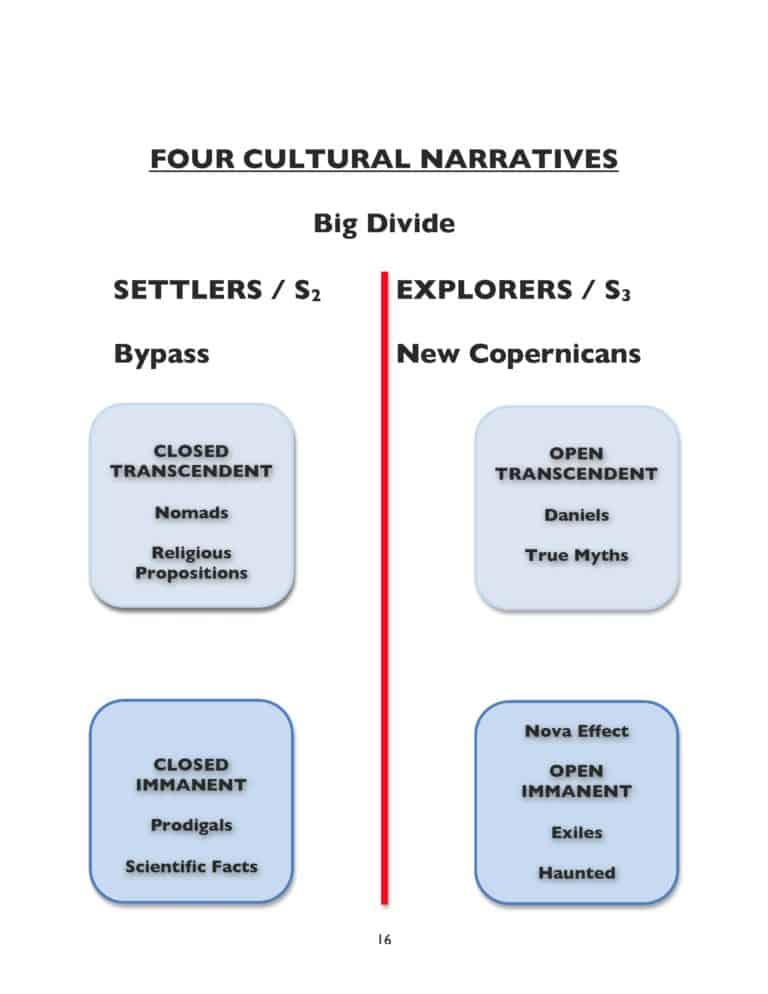

Another way to explore this cultural landscape is to consider the four distinct orientations to reality, cultural narratives or social imaginaries, that emerge from this analysis: closed transcendent, closed immanent, open immanent, and open transcendent (see figure below).[44] The dividing line down the middle of these four alternatives represents the fundamental shift in framing, the left side representing settlers, who adopt with certainty the illusionary matrix of the Enlightenment. The New Copernicans, or explorers, are found among the open immanent and open transcendent groupings on the right. Not all New Copernicans are religious or even spiritually oriented, but they do inhabit an open seeker’s world. Their posture is one of pilgrim, explorers, and seeker. There is no assumption that they have “arrived.” What they long for are fellow sojourners.

The closed transcendent and closed immanent are both culturally passé.[45] They represent large existing tribes that are no longer dominant or influential among those who curate the cultural narrative. Both closed transcendents and closed immanents will be potentially subject to institutional and cultural irrelevance in time. This is a point that institutional evangelicalism must come to understand. Today the only two groups that continue to use an either/or framing are religious leaders (closed transcendent) and academics (closed immanent).[46] In contrast, opinion leaders and young people use a both/and framing of reality. More importantly, the curators of the American social imaginary—the storytelling cultural creatives—are largely New Copernicans who adopt this new frame.

The four groups also have preferred forms of communication, a rhetorical bias, which reflect their left- or right-brain priority. Closed transcendents bias religious propositions, usually written statements. In a similar manner, the closed immanents bias scientific facts. In contrast, the open immanents prefer myths, stories, archetypes, poetry, music, and aesthetic expressions of longing and desire. It can be assumed that to reach closed immanents with the ancient Scriptures, they will need to be presented with the Scriptures within structures of their rhetorical bias.[47] The open transcendents prefer myths and stories that are linked to reality—in C.S. Lewis’ memorable words, “myths that are true.”[48] This perspective was embodied in the late Sir John Templeton, whose thinking was a blend of myth and science, signals of transcendence and the scientific method.[49]

The four groups also have preferred forms of communication, a rhetorical bias, which reflect their left- or right-brain priority. Closed transcendents bias religious propositions, usually written statements. In a similar manner, the closed immanents bias scientific facts. In contrast, the open immanents prefer myths, stories, archetypes, poetry, music, and aesthetic expressions of longing and desire. It can be assumed that to reach closed immanents with the ancient Scriptures, they will need to be presented with the Scriptures within structures of their rhetorical bias.[47] The open transcendents prefer myths and stories that are linked to reality—in C.S. Lewis’ memorable words, “myths that are true.”[48] This perspective was embodied in the late Sir John Templeton, whose thinking was a blend of myth and science, signals of transcendence and the scientific method.[49]

To the degree that there is ultimate value in an open transcendent perspective, the greatest challenge for the church is to move young people from Joseph Campbell to Jesus Christ, from myth to myths that are true, from pagan pilgrimages to a sacral home. It may be encouraging to remember that C.S. Lewis took this same journey in his life, moving from closed transcendent in his youthful Northern Ireland Anglicanism, to closed immanent atheism in his teen years, to open immanent under the influence of Yeats and Norse myths, to open transcendent through the encouragement of J.R.R. Tolkien and Hugo Dyson. Many today are retracing Lewis’ steps. This is the story of Michael McHargue, a.k.a. “Science Mike,” described in his forthcoming book, Finding God in the Waves: How I Lost My Faith and Found It Again Through Science (Random House, 2016).[50]

Most millennials are open immanent in perspective. In order to reach them the church must learn to capitalize on their sense of haunting, their ongoing suspicion that there is more to life than meets the eye. The church must also learn to adopt their relational, experience-driven approach to learning, life as muddling through with friends. Little is being done currently to equip pastors for this task. Instead, most of the debates and engagements with culture are confrontations between closed transcendents and closed immanents, which as far as cultural momentum, are largely beside the point. For New Copernicans they engender a yawn.

Those who have rejected the closed transcendent perspective of American evangelicalism are generally run out of their churches as heretics. One thinks of Rob Bell, Rachel Held Evans, and Frank Schaeffer, to name three.[51] We may not always agree with where they have landed in terms of lifestyle or theology, but we must learn to accept and appreciate their sensitivity to the new frame and respect their fight to find authentic expressions of faith within it. They are the prophets of the new sensibility.

The life trajectories represented by Bell, Evans, and Schaeffer are instructive. Their journeys are messy and painful. They can hardly talk about their spiritual journeys and their encounters with the church without anger. Closed transcendent institutions have emotionally brutalized them. Their forward-looking insights are often laced with understandable bitterness and anger toward the evangelical institutions that they have now either distanced themselves from or abandoned altogether. There are almost no on-ramps to an open transcendent perspective for children of closed transcendent parents or students at closed transcendent colleges and universities.

In today’s world children of evangelical parents are at risk of losing their spiritual orientation out of frustration. Open conversations about this new Copernican paradigm are generally not welcome even at Christian colleges—places where one might expect openness to diverse perspectives. New Copernicans on Christian college campuses are likely to delay their journey away from closed transcendence until graduation, because so few on-ramps exist for them to an open transcendent perspective. They are stuck and frustrated.[52] Many will become prodigals. It is not surprising to find that 74 percent of those now classified as “religious nones” grew up within the church.[53]

David Kinnamann, in his book You Lost Me: Why Young Christians Are Leaving the Church… and Rethinking Faith (Baker, 2011), describes young people as falling into three groups in terms of their association with the church: nomads, prodigals, and exiles. We would add Daniels to this list to fill out the four social imaginaries. His analysis parallels what we have found.

Nomads

Kinnamann describes children of closed transcendents as nomads. Closed transcendents parents have a transcendent perspective, which they hold with an unquestioned confidence bordering on arrogance. Reality for closed transcendents parents is framed in black-and-white religious propositions. Their children chafe at their narrow, self-righteous judgmentalism. A primary issue is tone and attitude. The main point of disagreement is framing—as much as it is specific matters of dogma or doctrine. Nomads have walked away from church but still consider themselves Christians. Faith has become for them an individualistic and private experience. Their public beef is largely with their parents and the institutional church in which their moms and dads participate. Because these children’s touchstone to reality is existential and relational, they bristle when their friends are criticized for their lifestyle choices. They resent the frequent aligning of conservative Christianity with right-wing politics. Most feel trapped in their churches as few have meaningful on-ramps to a more vibrant open expression of faith that is in keeping with their take on reality. Their response is to maintain faith but to abandon the church and church attendance. Religion for nomads is more than just taking attendance.

Rather than lament these attitudes in young people, we should celebrate their critique of Christendom, Enlightenment, and politics.[54] They are the ones with the courage to take the red pill. Their critique is with the 2D “either/or” framing represented by closed transcendents, not with religion per se. And yet, over time many nomads who are stuck or isolated with their frustrations with the institutional church give up and become prodigals.

Prodigals

Prodigals, as in the biblical parable, are those who have left their childhood home and gone to a far country. These young people no longer describe themselves as Christians and no longer attend church. Most adopt a closed immanent frame while in college, where attitudes toward science, the environment, race, and sexuality often serve to catalyze this shift.

The number of prodigals has grown in the past twenty years as the public stigma against describing oneself as an unbeliever or atheist has diminished. What would once have put one’s career and public standing at risk is now considered hip, edgy, and cool, thanks to the likes of Bill Maher and Greg Graffin, lead singer of the rock group Bad Religion.[55] Whether it is the science of evolution or the politics of climate change, prodigals eschew the anti-intellectual, anti-science, right wing, hetero-normative, black-and-white stance of their parents and childhood churches. Sometimes social scientists describe these youth as “religious nones,” merely because of their lack of church affiliation. Millennials uniformly dislike this description due to its false assumption that they are somehow anti-religious. Most are not. What they are against is secularism2, the 2D framing of religion in either/or categories, and the inevitable reliance on the over-confident religious assumptions of the Enlightenment. The problem is the frame, not the faith. But as institutional evangelicalism continues to rely on, and under pressure doubles down on Enlightenment categories, it is offering no help to these disenchanted and isolated youth. Consequently, the church and its reaction to these changes in the social imaginary often becomes its own worst enemy as far as their outreach to New Copernicans.

The closed immanent perspective has had a public relations surge in the last ten years with the advent of evangelistic atheism and the rise of the New Atheism. Leading proponents of this view have achieved a great deal of press, and many of their books have gone on to become bestsellers. This includes the intellectuals nicknamed the “Four Horsemen of the Non-Apocalypse”: Richard Dawkins (The God Delusion), Christopher Hitchens (God Is Not Great), Sam Harris (The End of Faith), and Daniel Dennett (Breaking the Spell). According to Dawkins, “We are all atheists about most of the gods that societies have ever believed in. Some of us just go one god further.” Even with the rise of “religious nones,” which should not be confused with New Atheism, this group is waning in influence and traction.

Exiles

This gives rise to the most interesting and growing social imaginary, the open immanent. This is where the church should pay close attention. This is where most millennials reside, and it is the quintessential New Copernican space. These are people who assume an immanent frame, “a constructed social space that frames lives entirely within a natural (rather than supernatural) order.” And yet, because of the provisional posture of their beliefs, open immanent young people in particular are constantly haunted by the possibility of something more, the yet unrecognized transcendent reality. For them, James K.A. Smith observes, “faith” is the doubt of their secularity.[56]

Kinnamann describes young people in this grouping as exiles, those who are still invested in their faith and church but are increasingly torn between their faith and the world they live in. The fact that the church is largely silent on how to navigate these realities and denies the validity of these tensions only makes their struggles more acute. How are they to relate to their LGBTQ friends? How are they to pursue relationships without acting on the assumptions of the hook-up scene? How are they to feel about the aspirations of the good life portrayed in Hollywood films and in television advertising? How are they to avoid the soft narcissism of the self-esteem, selfie-saturated culture? How are they to react to their parents’ politics and attitudes toward their friends, which leave them cold? How are they to respond to chronic police abuse toward Black men? How are they to process the high-profile hypocrisy of Christian leaders on Ashley Madison and the longing for romance depicted on The Bachelor/Bachelorette? The gnawing sense of irrelevance of the church and Christian belief to the world they are struggling to navigate on a daily basis is like an unhealed wound in their souls.

It is sometimes suggested that millennials have a low commitment to social capital, that they are not joiners. But this is not so. What is different is how and why they join groups. They do not join them on the basis of a shared commitment to abstract principles but on the basis of shared lived experiences that highlight inclusion, self-expression, community, participation, and immediacy (all of which are among the ten core values of Burning Man). They operate in technologically enabled pop-up relational hives, rather than in dogmatic or ideological institutional groupings.

Black Lives Matter is a case study in how they function. Fueled by social media, outrage over police brutality targeting Black men, and a shared experience of protest, this social movement has a democratic and relationally driven leadership structure consisting of an ad hoc policy platform that brings together young people with a wide assortment of priorities and agendas. Their website is primarily a communication portal for Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. When Hillary Clinton asked them for policy recommendations when they interrupted her campaign stop in Keene, New Hampshire, she asked the wrong question. Arguing that the movement can’t change deep-seated racism, Clinton said,

Look, I don’t believe you change hearts. I believe you change laws, you change allocation of resources, you change the way systems operate. You’re not going to change every heart. You’re not. But at the end of the day, we could do a whole lot to change some hearts and change some systems and create more opportunities for people who deserve to have them, to live up to their own God-given potential.[57]

This conversation was a matter of talking past one another, of non-communicating between two incommensurate frames. A better response by Clinton would have been, “When can I join you in your protest?” Solidarity is not affirmed by principle or policy but via a shared experience.

The tendency of boomers is to equivocate on Black Lives Matter’s core racial grievance, stating an alternative “All Lives Matter” or, worse, “Blue Lives Matter.” These statements are themselves forms of micro-aggression and unintended racism. It is to miss Black males’ shared street-level experience of being hassled and killed by police ten times more often than their white counterparts, of a world where a routine traffic stop becomes a potentially life-or-death matter. This is not simply a matter of getting the facts straight; it is a matter of operating from the same frame. It’s not about shared principles or policies, but about a shared experience.

Do millennials join things? Sure they do, and with a passion and commitment that puts others to shame. Critiques on their social capital are unfounded. How they express their social capital differs from previous generations. Social capital is expressed from below, from the messiness of lived experience, rather than from the bloodless abstractions of the classrooms, churches, or public policy think tanks.

If these assumptions about New Copernicans are true, then this cohort will bypass the typical closed transcendent church, the kind of church that makes up most of American evangelicalism. And this is what the numbers show.

Daniels

The final grouping is open transcendent, those who operate within a transcendent perspective, but hold their belief in the transcendent with an open-handed humility. It is this view that was modeled and celebrated by the late Sir John Templeton, a notion he called “humility-in-theology.”

While Humility-in-Theology counsels openness to new ideas and data, it is not meant to promote a “generic stance of openness” within the domain of religion. While Sir John was convinced that religion will progress when religious organizations and religious leaders adopt the special sort of humility that is characteristic of the sciences—one that is also characterized by rigorous methodology and conclusions grounded in evidence and sound argument, he did not seek himself to challenge or discredit long established religious tenets and values.[58]

Templeton advocated a spirit of exploration, curiosity, and a scientific rigor to discover an accurate assessment of human nature and reality. Science becomes an important aspect of open transcendence. This is what keeps subjective and therapeutic flights of fancy from going off the rails. In Lewis’ case, it was not the general celebration of any and all myths but finding the “myths that are also true.” Here we have a unique fusion of the left and right brain in reciprocal, collaborating harmony.

Exemplars of open transcendence, people like Sir John Templeton and the Templeton Prize winners since 1973, are not common folk. It is not common for a person to combine an open spiritual exploration with a rigorous pursuit of science. For this reason, there are few exemplars of open transcendent: C.S. Lewis and the Dalai Lama are two. And yet, this perspective is the hope of the church.

In his descriptive analysis of American youth, Kinnaman does not have a category for open transcendence, as he limits his analysis to three categories: nomads, prodigals, and exiles. Upon closer examination, exiles, or those with the experience of being homeless or stuck between two worlds, have both an immanent and a transcendent expression.

There is a benefit to being an exile. Costica Bradatan writes in the New York Times, “The redeeming thing about exile is that when your ‘old world’ has vanished you are suddenly given the chance to experience another. At the very moment you lose everything, you gain something else: new eyes.”[59] Marcel Proust adds, “The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes.”[60] One can read about the exile experience in a book, but there is no substitute from the knowledge that comes mixed with the blood and tears from this experience of existential uprooting.

The open immanent exile longs for the transcendent, while the open transcendent exile holds his transcendence convictions with a humble tentativeness. We can see that they need each other and are best kept in conversation with each other. But forums for such interactions are rare. In a pillarized and polarized world, these conversations are in short supply, particularly within institutional religion, where strict boundary maintenance is perceived as a high value. Creating forums for such interaction are a great need.

There are two biblical exemplars of an open transcendent exile that are worth noting: Daniel and Esther. Both were minorities in a foreign court. Both had to learn the cosmopolitan language of their center institutions. Both excelled in their daily interactions with their captors and compatriots. Both were transparent about their faith and commitments. Both were tested in them at the point of death.

The American evangelical church is learning again what is required for it to function effectively as a minority community, as experiential exiles within an alien social imaginary. University of Virginia sociologist James Davison Hunter states, “Ours is now, emphatically, a post-Christian culture, and the community of believers are now, more than ever—spiritually speaking—exiles in a land of exiles. Christians, as with the Israelites in Jeremiah’s account, must come to terms with this exile.”[61] University of North Carolina historian Molly Worthen adds that American evangelicals must learn today how to act publicly after the collapse of Christendom.[62] This challenge will bring with it spiritual vitality and authenticity. The natural teachers, in facing this challenge, are millennial New Copernicans.

The shared neopagan journey

Likewise, church believers need to learn to embrace the pagan spiritual journey of others and to walk with those who are on it, in a nonjudgmental manner. Neopaganism is often the spiritual starting place for New Copernicans, the ground zero of the “nova effect.” We must learn to affirm the saliency of the spiritual exploration itself before asserting the posture of guide or guru to others.

Neopaganism is the spiritual voice of popular culture. Art historian Camille Paglia writes, “If you look at it from my perspective, popular culture is an eruption of paganism—which is also a sacred style…. We are steeped in idolatry. The sacred is everywhere. I don’t see any secularism. We’ve returned to the age of polytheism. It’s a rebirth of pagan gods. Judeo-Christianity never defeated paganism, but rather drove it underground.”[63] Now that Judeo-Christianity is in cultural decline or cultural exile, what was once underground is now resurfacing as a viable means of spiritual communion. Expressed in a multitude of ways, spiritual communion is dearly sought after by New Copernicans. Singer-songwriter Jewel asks, “Who will save your soul if you won’t save your own?” Many teenagers are finding neopaganism the perfect answer. In the same spirit, The Fray’s Isaac Slade asks God,

Lost and insecure

You found me, you found me

Lyin’ on the floor

Surrounded, surrounded

Why’d you have to wait?

Where were you? Where were you?

Just a little late

You found me, you found me[64]

Popular culture is steeped in the New Copernican spiritual experience. Yet the mere mention of neopaganism in some Christian circles invites responses of hysteria—images of Wiccan witches and occultist come to mind. We should reread C.S. Lewis: “Christians and pagans had much more in common with each other than either has with a post-Christian. The gap between those who worship different gods is not so wide as that between those who worship and those who do not…”[65] Lewis is saying that open transcendence and open immanent have much more in common than with the close immanent. Lewis’ observation parallels Father Halik’s quote above. Exiles, whether immanent or transcendent, are spiritual travel companions, brothers and sisters in a common soul exploration. But clearly the church needs to learn to build bridges, something that is mostly impossible from a close transcendent position.

The church must take the red pill, abandon the assumptions of the Enlightenment and embrace the New Copernican. Thomas Molnar states, “The spiritual vacuum that prevails in modern society with the complicity of the church makes it quite natural for people to turn to pagan religions and the occult, even as two thousand years ago people turned from paganism to more emotion-laden creeds and to Christianity.”[66] Christian churches are too often business enterprises and doctrinal fortresses before they are spiritually humane communities. There is more authenticity and non-judgmental acceptance in an Alcoholic Anonymous meeting than in most church community groups.

Consider, by contrast, St. Lydia’s Church in Brooklyn, New York. Here the entire worship service is experienced around a dinner table and a shared meal. It is a welcoming, journeying, exploring church where they “are working together to dispel isolation, reconnect neighbors, and subvert the status quo.”[67] Here is an exemplar New Copernican church.

This journey will also require that one engage matters of common concern: the environment, police brutality, LGBTQ issues, homelessness, relationship breakups, and a host of other matters of messy lived reality in an urban setting. This is not a journey for the fainthearted or those unwilling to get dirty; to face controversy, or to remove their doctrinal positions from neatly wrapped sanitized boxes. This is L’Abri, Taize, Iona and Burning Man all rolled up into one experience. It is here that authentic Christ-like experience is revealed. We need more of it, not less.

Theologian Carl Braaten argues “The outcome of the encounter of the gospel with our neopagan culture will be decided by the strength of our Christology.”[68] We would simply add that it must not be the Christology of the systematic theology textbook but the Christology of “Patrick’s Breastplate”:

Christ within me, Christ before me, Christ behind me,

Christ in me, Christ beneath me, Christ above me,

Christ on my right, Christ on my left,

Christ where I lie, Christ where I sit, Christ where I arise,

Christ in the heart of every man who thinks of me,

Christ in the mouth of every man who speaks of me,

Christ in every eye that sees me,

Christ in every ear that hears me.

It is our contention that millennial New Copernicans “think different.” It is this difference that makes them the future hope of the American church.

In summary, we suggest ten implications from this analysis of the New Copernican thesis.

- Bypass: If we maintain the status quo and do not take this New Copernican shift in the cultural narrative or social imaginary seriously, we will be culturally bypassed. We can decide our own irrelevance.

- Trump Cards: To succeed in these conversations will require recognizing that there are a different set of tools, attitudes, and trump cards needed. We will need to retool our leadership and institutions to effectively meet these challenges.

- Frontlines: Reaching spiritually oriented millennials or New Copernicans is the cultural frontline in our effort to engage the soul of America in the new millennia. Martin Luther warned against fighting the wrong battles in his day, “Where the battle rages, there the loyalty of the soldier is proved, and to be steady on all the battlefield besides, is mere flight and disgrace if he finches at that point.”[69] New Copernicans are the frontline in the church’s engagement with culture.

- Attitude: We must learn to adopt a seeker’s attitude—one that includes humility, openness, authenticity, and relationality. If we continue to be seen as confident self-righteous know-it-alls, we will be excluded from the cultural conversation. We have already acquired a pretty damning cultural reputation. We will need to take steps that challenge these negative expectations.

- Journeying: We must learn to join the spiritual journeys of others without positioning ourselves as the guides or gurus. Salt adds flavor to food. So too apprentices of Jesus should add human vitality and richness to the lives of those we are with. We join in their journey because we too are on a journey and they may have much to teach us. At the very least, they can teach us to be more empathetic and less judgmental.

- Haunting: We must learn to appreciate spiritual openness, the restlessness of a haunted sensibility. We must learn to expect and accept the “nova effect,” the explosion of different options for belief and meaning in a post-secular age, without judgment. The common enemy is a world without windows.

- Experience: We must learn to see the parallels between religious longing and relational desire, something we can readily accept, as we believe that reality is fundamentally relational. Can we acknowledge the relational longing, the search for love, without getting immediately moralistic about sex? We must learn to prioritize lived experience over cognitive abstractions, even when this approach may leave one in the midst of ambiguity, paradox, and unresolved messiness.

- Celtic Christianity: We believe that there are untapped resources that can be learned from ancient Celtic Christianity. Patrick’s 5th-century engagement with the Druid culture has many parallels to our own day. Here is a gritty, dirt-under-the fingernails spirituality aligned to our contemporary needs. It is decidedly pre-Enlightenment, which is why it fits.

- Science: Science will be a very important and helpful part of our cultural conversation as the engagement with science will promote a methodological openness to new ideas and force the spiritual engagement with a reality that is larger and other than the confines of one’s subjective ego. We need to bolster the relationship of spirituality to creation.

- Hope: We will have to accept the New Copernican attack on Christendom, its foundational critique of the religious status quo. It is our belief that millennial New Copernicans think different and that it is just this difference that is the hope and future of the American church. Millennial New Copernicans are carriers of a new social imaginary that is in the end a more accurate assessment of human nature and reality and as such will lead us to a more humane world and a more vital spirituality.

John Seel directs the Sider Center’s New Copernican Empowerment Dialogues. He is the founder and principal of John Seel Consulting LLC, a social impact/cultural renewal consulting firm. He was formerly the director of cultural engagement for the John Templeton Foundation and associate research professor at the University of Virginia working at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture. He is an authority on reaching the millennial generation. Seel has an M.Div. from Covenant Theological Seminary and a doctorate in American Studies from the University of Maryland at College Park.

Notes:

[1] For a series of videos on New Copernicans see http://www.windriderforum.info/productions/new-copernicans-series/.

[2] Gingerich, Owen. The Book Nobody Read: Chasing the Revolutions of Nicolaus Copernicus (Penguin, 2004).

[3] James White, The Rise of the Nones, (Baker, 2014); Cary Funk and Greg Smith, “’Nones’ on the Rise: One-in-Five Adults Have No Religious Affiliation, (Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life (October 2012); https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Millennials; http://www.pewresearch.org/topics/millennials/; Making Space for Millennials: A Blueprint for your Culture, Ministry, Leadership, and Facilities, (Barna, 2014).

[4] Walter Issacson, Einstein: His Life and Universe, (Simon & Schuster, 2008).

[5] Kate Crawford, “The Hidden Biases in Big Data,” Harvard Business Review, April 2013.

[6] Lisa Gitelman, Raw Data Is an Oxymoron, (MIT, 2013).

[7] Barbara Herman, “Why Matthew McConaughey’s Lincoln Car Ad Is A Big Deal, Signals a Cultural Shift In Ideas About Celebrity, TV’s Status, And Commercialism,” International Business Times, October 17, 2014.

[8] Joseph O. Rentz and Fred D. Reynolds, Separating Age, Cohort and Period Effect in Consumer Behavior, Advances in Consumer Research Volume 08, pp. 596-601.

[9] Rich Bellis, “Millennials Aren’t More Motivated By ‘Purpose’ than the Rest of Us,” Fast Company, July 5, 2016, http://www.fastcompany.com/3061441/the-future-of-work/millennials-arent-more-motivated-by-purpose-than-the-rest-of-us/.

[10] Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Harvard, 2007), p. 171-172.

[11] James K.A. Smith, Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation (Baker, 2009), p. 66.

[12] Ibid., p. 16.

[13] Brian Chen, Always On: How the iPhone Unlocked the Anything-Anytime-Anywhere Future — and Locked Us, (Da Capo, 2011); Kathleen Bogle, Hooking Up: Sex, Dating, and Relationships on Campus, (NYU, 2008); Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, (Norton, 2011); Jean Twenge, The Narcissism Epidemic: Living in the Age of Entitlement, (Atria, 2010); Jamie Barromeo, Young, Educated, & Broke: An Introduction to America’s New Poor, (Morgan James, 2015).

[14] Charles Taylor, The Ethics of Authenticity, (Harvard, 1995), p. 37.

[15] C.S. Lewis, “Bluspels and Flalansferes: A Semantic Nightmare,” Selected Literary Essays, (Cambridge, 2013), p. 265.

[16] George Lakoff, Don’t Think of the Elephant!: Know Your Values and Frame the Debate, (Chelsea Green, 2014), p. 17.

[17] Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue (Notre Dame, 1981), p. 216.

[18] Iain McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, (Yale, 2010), p. 137.

[19] https://www.ted.com/talks/iain_mcgilchrist_the_divided_brain.

[20] This is the central thesis of McGilchrist’s The Master and His Emissary.

[21] Paul H. Ray and Sherry Ruth Anderson, The Cultural Creatives: How 50 Million People Are Changing the World, (Broadway, 2001).

[22] The actual quote, “Cultural influence is not measured by the size of one’s organizations or by the quantity one’s output, but by the extent to which one’s definition of reality is realized—and taken seriously and acted upon by the influential players in the social world.”

[23] Quoted in John Seel, “The Preconditions of Cultural Influence: A Case Study of Inherit the Wind, Critique, http://www.ransomfellowship.org/articledetail.asp?AID=299&B=David%20John%20Seel,%20Jr.&TID=2/.

[24] Rick Lyman, “Not All Will Follow This Star in the East,” The New York Times, July 4, 2014.

[25] Peter Berger, A Rumor of Angels: Modern Society and the Rediscovery of the Supernatural, (Anchor, 1970).

[26] Charles Taylor, A Secular Age, (Harvard, 2007), pp. 423-535.

[27] Lesslie Newbigin notes, “The churches of Europe and their cultural offshoots in the Americas have largely come to a kind of comfortable cohabitation with the Enlightenment.” Proper Confidence: Faith, Doubt, and Certainty in Christian Discipleship, (Eerdmans, 1995), p. 33.

[28] James K.A. Smith, How (Not) To Be Secular: Reading Charles Taylor, (Eerdmans, 2014), p. 142.

[29] Ibid., p. 143.

[30] Seth Godin’s blog, “None of the Above,” April 8, 2016.

[31] Ibid., p. 73.

[32] Julian Barnes, Nothing To Be Fightened Of, (Vintage, 2008), p. 3.

[33] Ross Douthat, “I Love Lena,” The New York Times, October 4, 2014.

[34] Jeffrey Satinover, “Jungians and Gnostics,” First Things, October 1994, pp. 41-48.

[35] See Alissa Wilkerson and Robert Joustra’s How to Survive the Apocalypse: Zombies, Cylons, and Politics at the End of the World, (Eerdmans, 2016).

[36] Adapted from John Seel, “All That Glitters Is Not Gold,” On Earth As It Is in Heaven, May 18, 2015.

[37] Neuroscientist McGilchrist states, “Certainty is the greatest of all illusions: whatever kind of fundamentalism it may underwrite, that of religion or of science, it is what the ancients meant by hubris.” p. 460.

[38] Philosopher James K.A. Smith writes, “The picture of knowledge bequeathed to us by the Enlightenment is a forthright denial of our dependence, and it yields a God-like picture of human reason…. Christians know their contingency is a correlative to their status as creatures.” Who’s Afraid of Relativism: Community, Contingency, and Creaturehood, (Baker, 2014), p. 35, 36.

[39] Michael Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension, (Chicago, 2009); Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy, (Chicago, 2015).

[40] See Megan DeFranza’s Sex Difference in Christian Theology: Male, Female, and Intersex in the Image of God (Eerdmans, 2015).

[41] McGilchrist, p. 137.

[42] John Templeton, “What is Humility-in-Theology?”

[43] “In the Celtic world, the high-standing crosses that are rooted deep in the ancient landscape express the belief that Christ and creation are inseparably interwoven. Two images combine to make one form in the Celtic cross. Christ, represented by the cross, and creation, represented by the orb at the heart of the cross, are one.” J. Philip Newell, Christ of the Celts: The Healing of Creation, (Josey-Bass, 2008), p. xvi. McGilchrist adds, “No straight lines are to be found in the natural world. Everything that really exists follows a series of curved shapes.” p. 447.

[44] James K.A. Smith, How (Not) To Be Secular, (Eerdmans, 2014), p. 95.

[45] McGilchrist observes, “In the field of religion there are dogmatists of no-faith as there are of faith, and both seem to me closer to one another than those who try to keep open the door to the possibility of something beyond the customary ways in which we think, but which we would have to find, painstakingly, for ourselves.” p. 460.

[46] This suggests that most Christian college students are doubly damned with a closed “either/or” perspective as the religious and academic orientation mutually reinforce themselves.

[47] This one of lasting strengths of New Zealand-based Scarlett City Studios online game, “The Aetherlight: The Chronicles of Resistance.” In a “been-there, done-that” world, the gospel will need to be reframed in a fresh manner to reach future generations.

[48] “Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened: and one must be content to accept it in the same way, remembering that it is God’s myth where the others are men’s myths: i.e., the Pagan stories are God expressing Himself through the minds of poets, using such images as He found there, while Christianity is God expressing Himself through what we call ‘real things’.” — C.S. Lewis

[49] John M. Templeton and Robert L. Hermann, The God Who Would Be Known, (Templeton, 2012). See also David Howitt, Heed Your Call: Integrating Myth, Science, Spirituality, and Business, (Atria, 2014).

[50] http://www.windriderforum.info/portfolio_page/episode-11-mystical-experience/.

[51] Rob Bell, Jesus Wants to Save Christians: Learning to Read a Dangerous Book, (HarperOne, 2012); Rachel Held Evans, Searching for Sunday: Loving, Leaving, and Finding the Church, (Nelson, 2015); and Frank Schaeffer, Why I Am an Atheist Who Believes in God: How to Give Love, Create Beauty, and Find Peace, (Regina Orthodox, 2014).

[52] See Deborah Jian Lee’s description of “progressive evangelicalism” and its growth among institutional evangelicalism: Rescuing Jesus: How People of Color, Women, & Queer Christians Are Reclaiming Evangelicalism, (Beacon, 2015).

[53] Cary Funk and Gregory A. Smith, “Nones” on the Rise: One-in-Five Adults Have No Religious Affiliation, (Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life, October, 2012), p. 16.

[54] Jiddu Krishnamurti wisely notes, “It is not a good idea to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society.” Quoted in Howlett, p. 125. See also Soren Kierkegaard, Attack on Christendom 1854-1855, (Princeton, 1968).

[55] Preston Jones, Is Belief in God Good, Bad or Irrelevant?: A Professor and a Punk Rocker Discuss Science, Religion, Naturalism Christianity, (InterVarsity, 2006).

[56] James K.A. Smith, How (Not) To Be Secular, p. 9.

[57] Russell Berman, “Hilary Clinton’s Blunt View of Social Progress,” The Atlantic, August 22, 2015.

[58] John M. Templeton, ibid.

[59] Costica Bradatan, “The Wisdom of Exiles,” The New York Times, August 17, 2014.

[60] Howlett, p. 13.

[61] James Davison Hunter, To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy, & Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World, (Oxford, 2010), p. 277. Jeremiah 29:1-7.

[62] Molly Worthen, Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism, (Oxford, 2013).

[63] Lewis H. Lapham, “She Wants Her TV! He Wants His Book!,” Harper’s Magazine, March, 1991.

[64] Lyrics to “You Found Me” by The Fray

[65] C.S. Lewis, “De Descriptione Temporum,” They Asked for a Paper, (Geoffrey Bles,1962).

[66] Thomas Molnar, The Pagan Temptation, (Eerdmans, 1987).

[67] Emma Green, “The Secret Christians of Brooklyn,” The Atlantic, September 8, 2015.

[68] Carl Braaten, Either/Or: The Gospel or Neopaganism, (Eerdmans, 1995).

[69] Quoted in Francis Schaeffer, The God Who Is There, (InterVarsity, 1968), p. 18.

I was unfamiliar with this term as a noun. So I looked it up and learned that it is a sociology term. “The imaginary, or social imaginary is the set of values, institutions, laws, and symbols common to a particular social group and the corresponding society through which people imagine their social whole.” If your audience is a popular one and not necessarily an academic one, I suggest you define this term the first time you use it.

2 Responses

Dr. Seel, do you have any full-length books? I am fond of your writing and thoughts

My new book, “The New Copernicans,” has just been released by Thomas Nelson.