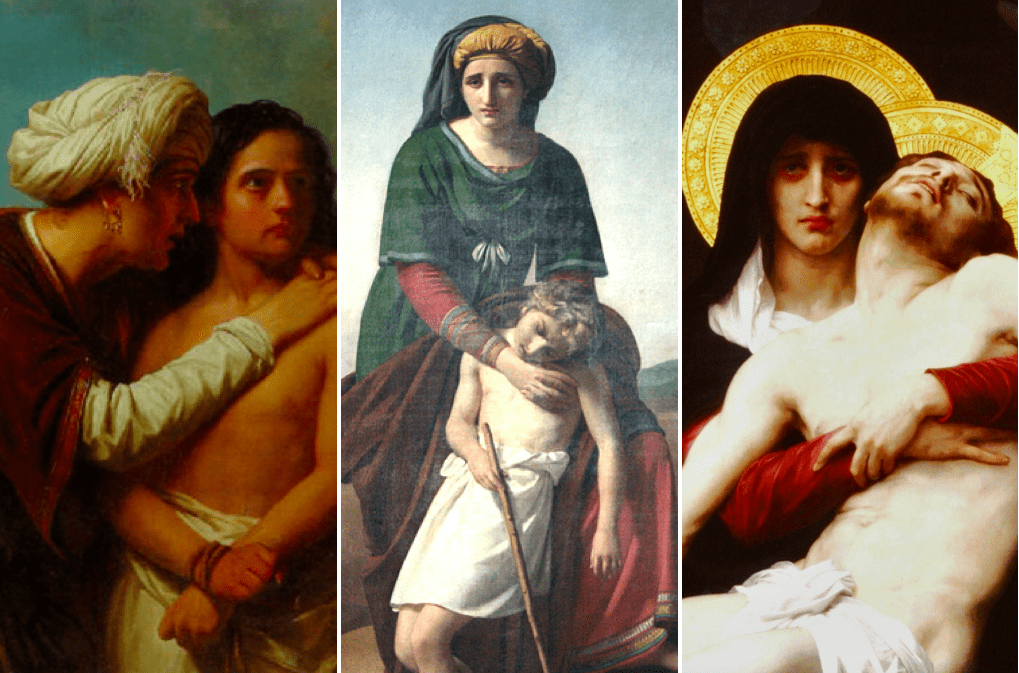

Imagine three women standing in a town square, facing each other and reflecting on the current Middle East situation. These three women have just come from their respective places of worship. The oldest woman is Sarah, a Hebrew woman, the wife of Abraham, and matriarch to Isaac and Jacob. She has been sitting in a synagogue grieving and lamenting, “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down and there we wept when we remembered Zion. On the willows there we hung up our harps. For there our captors asked us for songs, and our tormentors asked for mirth, saying, ‘Sing us one of the songs of Zion!'” (Psalm 137:1,2)

In the synagogue, she has wept over repeated persecutions of the Jews. She has sobbed over the holocaust. She has pleaded to know when the swords would be beaten into plowshares.

Out of a mosque has come Hagar, once the Egyptian slave of Sarah. Within the customs of her times, Hagar joined with Abraham to become a surrogate mother to the child Sarah longed to have. But when Sarah had a child of her own, she feared for that child and cast Hagar and the child out into the desert near Canaan. This child was Ishmael, progenitor of a people God said would be too numerous to count. Hagar has watched these children of Abraham become inhabitants of the Arabian peninsula and its surroundings. The trials of her distant son, Mohammed, draw Hagar into the mosque where she begins to chant: “O people, we created you from the same male and female, and rendered you distinct peoples and tribes, that you may recognize one another. The best among you in the sight of GOD is the most righteous. GOD is Omniscient, Cognizant” (QUR’AN: [49:13]). She has pondered the destruction of her son’s people throughout history – the repeated assaults of the crusaders, the betrayal of promises made by the British government to the Arabs, the arbitrary carving up of the Ottomon Empire into badly-bordered states by the World War I victors.

Into the town square out of a church appears Mary, mother of the Christian faith’s author and perfecter, Jesus. Mary has asked God how many swords would pierce her soul. When would God perform mighty deeds with God’s powerful arm and scatter those who are proud in their inmost thoughts? What of the persecution of Christians in hidden outpost pockets such as the Sudan, Nigeria, Pakistan, India and Indonesia?

Face to face in the public square, the eyes of these women move back and forth. They now do not see the enemies of their children as faceless strangers, but as mothers with broken hearts. To see each other’s faces this way reminds them that Abraham was the father of many nations, not just the father of their child’s people, that “those who believe are children of Abraham.” They sing together songs of lament: “Hear, O Lord, when I cry aloud! Do not cast me off, do not forsake me, O God of my salvation!” (Psalm 27:7,9) They lament together: Why are these children of Abraham bent on having their own way? Why doesn’t God impel them to love one another, to treat one another as brothers and sisters?

They now do not see the enemies of their children as faceless strangers, but as mothers with broken hearts.

Reviewing the histories of their children’s people, each woman understands that God does not intervene because God allows people freedom to choose to trust or not trust God. What love knows is that love – even divine love – doesn’t force or manipulate or control. Love respectfully allows people to make their own mistakes, even if means doing evil things.

Their prayer is that in this freedom of choice, their peoples will choose love. Possibility for peace lies in the choice to sit down together and perhaps to weep and sing together. To look into the eyes of our so-called enemies (also children of Abraham) presents the choice to love the person who has done evil. And so Hagar and Mary and Sarah sit and sing together, challenging us all to make choices that will bring peace and reconciliation and an end to the centuries-old war among the children of Abraham.

Jan Johnson is a writer in Simi Valley, CA who specializes in spirituality and social justice.